9. On the human body as the locus of Albert Camus’ thought

And how the body grounded his literary imagination in the theatre

1.

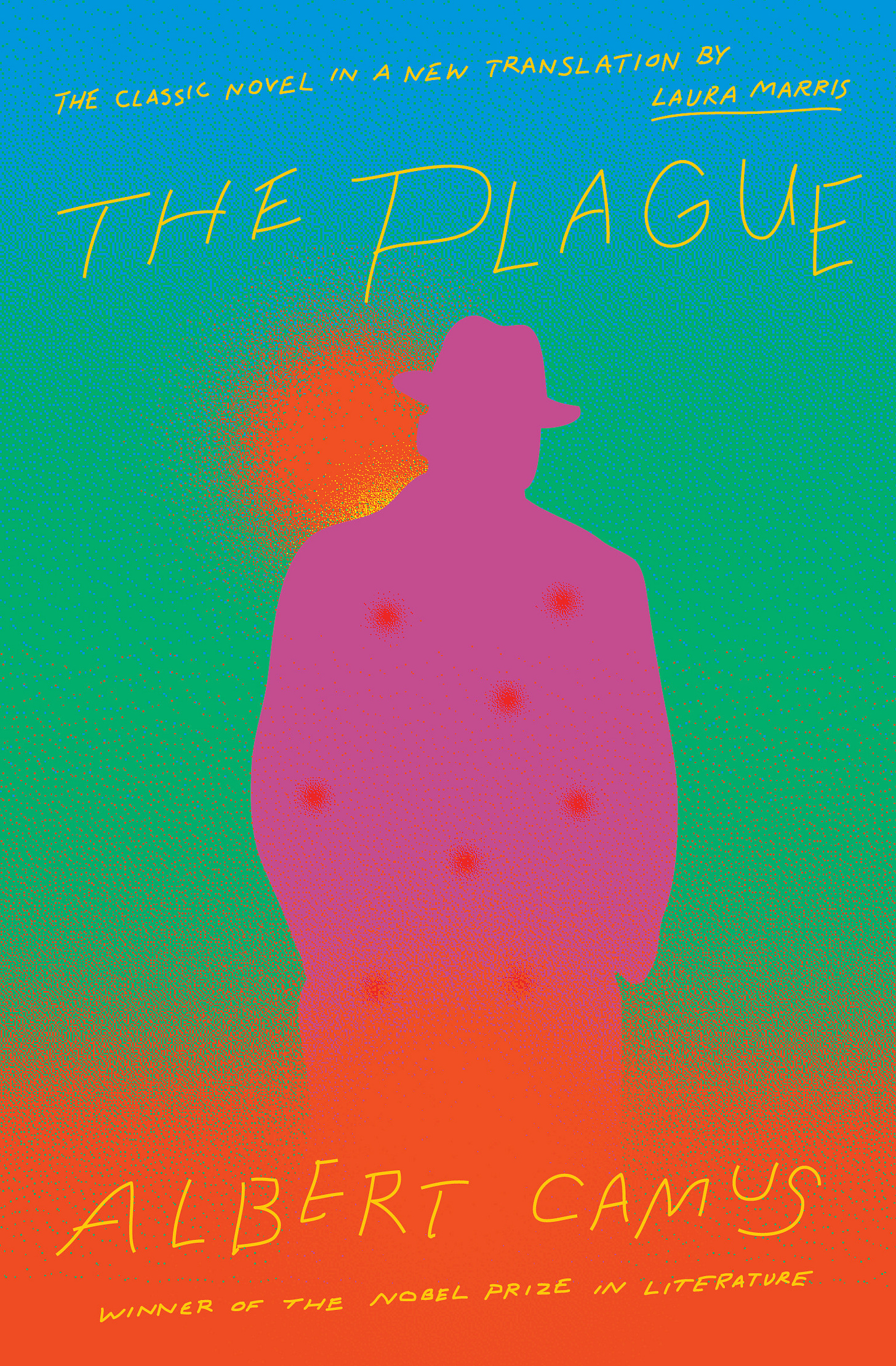

We’ve already examined how the experience of tuberculosis influenced Albert Camus’ life and work, and how it shaped his literary imagination (here), culminating in his composition of The Plague (here). His experience with chronic illness also influenced his thinking more generally. In March 1951, in his notebooks, drafting a preface to the republication of his lyrical essays from the 1930s, Camus wrote that, yes, his illness added obstacles to his life: ‘But in the end, it [his tuberculosis] has fostered this freedom of heart, this slight distance with regard to human interest, which has always kept me from bitterness and resentment.’ In particular, this distance brought his body and its limitations to the centre of his thinking. Or, rather, it may be more correct to say it brought his thinking and its limitations to be grounded more self-consciously in his body.

Arguably, the most fundamental insight for understanding Camus, the kernel of his thought, can be found outlined in his notebooks, from 1938:

Thought is always out in front. It sees too far, farther than the body, which lives in the present.

To abolish hope is to bring thought back to the body. And the body is doomed to perish.

In Nuptials, the collection of lyrical essays he published the following year, Camus kept returning to this troubled value of the body, around which he reconfigured all his other judgements. In “Nuptials at Tipasa”, for example, he states: ‘For me it is enough to live with my whole body and bear witness with my whole heart.’ In “Summer in Algiers”, he describes Algerian culture in this tenor: ‘It worships and admires the body. From this comes its strengths, its naïve cynicism, and a puerile vanity that leads it to be severely criticized.’ Again, regarding his fellow Algerians: ‘They have wagered on the flesh, knowing they would lose.’ Meanwhile, in “The Desert”, Camus begins defining an ethical attitude which he will later develop in The Myth of Sisyphus, built upon revolt, but one confined here to the body and the present moment:

It is in joy that man prepares his lessons and when his ecstasy is at its highest pitch that the flesh becomes conscious.... These twin truths of the body and of the moment, at the spectacle of beauty – how can we not cling to them as to the only happiness we can expect, one that will enchant us but at the same time perish?

Here Camus differentiates his own position from other positions that supposedly base themselves on the body, but in effect don’t go further than some concept of the “body”, which Camus sees as really being a disembodied intellectual attitude that ultimately betrays the body, making of it simply an object of thought, rather than its very taproot. ‘Many people, in fact, affect a love of life in order to avoid love itself,’ he writes in “Summer in Algiers”. ‘They try to enjoy themselves and “to experiment”. But this is an intellectual attitude. It takes a rare vocation to become a sensualist.’

On this basis, Camus likewise rejected those who advocate for a naïve materialism: ‘The most loathsome materialism is not the kind people usually think of, but the sort that attempts to let dead ideas pass for living realities, diverting into sterile myths the stubborn and lucid attention we give to what we have within us that must forever die.’

And yet, at the same time, he also distanced himself from automatically falling into the other extreme, foreshadowing his later argument in The Myth of Sisyphus against religious hope:

The immortality of the soul, it is true, engrosses many noble minds. But this is because they reject the body, the only truth that is given them, before using up its strength. For the body presents no problems, or, at least, they know the only solution it proposes: a truth which must perish and which thus acquires a bitterness and nobility they dare not contemplate directly.

In “Summer in Algiers” Camus defends those (including himself) who simply enjoy the sun and the sea, against those who try to intellectually justify such activities. ‘Not that they have read the boring sermons of our nudists,’ he states,

those protestants of the body (there is a way of systematizing the body that is as exasperating as systems of the soul). They just “like being in the sun”. It would be hard to exaggerate the significance of this custom in our day. For the first time in two thousand years the body has been shown naked on the beaches. For twenty centuries, men have strived to impose decency on the insolence and simplicity of the Greeks, to diminish the flesh and elaborate our dress.

It is against these ‘systematizers’ of the body that Camus is seeking, for himself, an unsystematic counter-practice. And yet, Camus does not scorn the intelligence, or dissuade reflection upon these experiences, for he sees in these physical explorations a certain value, which he does not want to betray. ‘Living so close to other bodies,’ he states, ‘and through one’s own body, one finds it has its own nuances, and, to venture an absurdity, its own psychology.’ It is this figurative ‘psychology’ of the body – or, rather, a ‘psychology’ from the body, a thinking that operates within the limits of bodily experience – that Camus outlines in these early essays, of flesh becoming conscious. This is supported in the notebooks he kept during this period, in which he speaks of ‘a self-knowledge which one gains through the body. The body, a true path to culture, teaches us where our limits lie.’

Or, as he notes, more succinctly: ‘Culture – the body’.

2.

These reflections soon came to structure Camus’ arguments in The Myth of Sisyphus. The theme of suicide – which opens the discussion of the first part of that book – turns on the question of bodily self-destruction, on asking whether or not the body itself can be brought into question. Camus’ eventual denial of the legitimacy of suicide is hinted at only a few pages later, however, when he states: ‘The body’s judgment is as good as the mind’s, and the body shrinks from annihilation. We get into the habit of living before acquiring the habit of thinking. In that race which daily hastens us toward death, the body maintains its irreparable lead.’ This reversal of the initial problem is significant – and often overlooked – because it is predicated upon the final understanding, which the remainder of that essay bears out, that the body itself cannot be brought into question.

Like the theme of suicide, the experience of the absurd is structured by certain motifs that always include the body. Camus describes the experience, for example, as assuming one’s place in time and the inevitable loss of youth: ‘That revolt of the flesh is the absurd.’ Other experiences of the absurd include our physical appearance: ‘the stranger who at certain seconds comes to meet us in the mirror, the familiar and yet alarming brother we encounter in our photographs.’ Or else, it comes from seeing a person, behind a pane of glass, reduced to their bodily movements alone: ‘the mechanical aspect of their gestures, their meaningless pantomime makes silly everything that surrounds them’. Finally, there is death itself, in which the only experience we can have is of other people’s death, rather than our own: ‘From this inert body on which a slap makes no mark the soul has disappeared. This elementary and definitive aspect of the adventure constitutes the absurd feeling.’

It is in this context that Camus introduces the theme of hope into Sisyphus, as a form of resignation, in which – whether it be through adopting a philosophical system, a religious doctrine, or a political ideology – a person develops a habit of thinking that fancies it is always one step ahead of the body, and is somehow, for that reason, on firmer ground: ‘Hope of another life one must “deserve” or trickery of those who live not for life itself but for some great idea that will transcend it, refine it, give it meaning, and betray it.’ This is an argument against hope, against such betrayal of the human body, which Camus rehearsed in his earlier lyrical essays. ‘From the mass of human evils swimming in Pandora’s box, the Greeks brought out hope at the very last, as the most terrible of all,’ he wrote in “Summer in Algiers”. ‘I don’t know any symbol more moving. For hope, contrary to popular belief, is tantamount to resignation. And to live is not to be resigned.’

For Camus, abolishing such hope brings thought back within the limits of the body – or, rather, it shows thought has never left these limits, and only ever created the illusion of doing so – whether that be through subordinating oneself to a system, a doctrine, or an ideology – often to the detriment of the body itself: those little creations we carry around in our heads that we use to keep reality, including the reality of our own bodies, at bay, and which it requires a plague to rid ourselves of. Or a private illness. Or a pandemic.

3.

In the second part of Sisyphus, Camus describes three figures – the Don Juan, the Actor, and the Conqueror – each in their own way being conscious of the absurd, and rebelling against it, but without retreating into either hope or suicide. In this, these figures are once more described as being grounded in and by their bodies. The figure of Don Juan, for example, as a lover and a seducer, lives by and for the human body, his own and that of others. Likewise, the Conqueror: ‘For the path of struggle leads me to the flesh. Even humiliated, the flesh is my only certainty. I can live only on it. The creature is my native land.’ Finally, the Actor: ‘The theatrical convention is that the heart expresses itself and communicates itself only through gestures and in the body... The rule of that art is that everything be magnified and translated into flesh.’

This figure of the actor, in particular, points to a fundamental aspect of Camus’ life and work that is key to understanding the importance he placed on the role of the body. For some writers, the parts of their work which are most acclaimed by the public, and on which their fame may very well be premised, is not necessarily the part of their work which the writer prioritised or emphasised in their own life and creative practice. For Camus, he is best known for his narrative fiction, and then for his non-fiction books (although it is arguable how well these are read). But what he is celebrated least for is his work in the theatre. And yet, arguably, this is where he spent much of his time, and poured most of his creative energies into. The theatre, in turn, contributed greatly toward his own thinking, informing, in turn, both his narrative fiction and non-fiction books, and the imagery and thoughts contained therein.

To provide some context: during his lifetime, Camus published three novels (The Stranger, The Plague and The Fall), and a collection of short stories (The Exile and the Kingdom). He had an unpublished manuscript for a novel completed in 1938 (The Happy Death) and he was working on another novel manuscript when he died in January 1960 (The First Man). He also published two book-length essays (The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel), and three collections of lyrical essays (The Wrong Side and the Right Side, Nuptials, and Summer). But during the same period he published and directed four of his own plays (Caligula, The Misunderstanding, State of Siege, The Just) and in the last decade of his life, he adapted and directed another six plays (including William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Possessed). So, purely on a level of creative output, we can see that in his lifetime Camus published more original plays than he did novels. And he wrote (including adaptations) and directed nearly as many plays as he did novels (published and unpublished), collections of stories, book-length essays, and essay collections, combined.

But this does not yet take into account, furthermore, the plays he wrote, adapted, directed, and acted in during the late 1930s in Algeria. In fact, Camus’ first creative outlet in his 20s was the theatre. Between 1935 and 1939 Camus was the director of two amateur theatre companies, with a transition from one company to the second in 1937. He was involved in the writing and adapting, directing, and acting of various plays. The first company (Théâtre du Travail) produced six plays (one of which was banned before performance). Of these six, Camus adapted two, and co-wrote a third (banned), and directed/acted in them all. The second company (Théâtre de l’Équipe) produced five plays and worked on an additional four productions. Of the plays produced, Camus adapted one and directed/acted in them all, and of the projected four, Camus adapted/translated two and wrote a third (the first draft of Caligula, 1938). Including these in the ledger, his theatrical output far surpasses that of his other literary pursuits.

One year before his death Camus wrote an essay called “Why I Work in the Theatre.” It begins:

Why do I work in the theatre? I’ve often asked myself why. And up to the present, the only answer I’ve been able to make will strike you as discouragingly banal: simply because the theatre is one of the places in the world in which I am happy.

Look out, though; that reflection is less banal than it seems.

It is in this context that he brings out the importance of the body within the theatre, relating it to the practice of virtue: ‘Acting is a profession in which the body counts, not because it is used profligately, but because one is constrained to keep it in shape. Being virtuous is a matter of necessity, which is perhaps the only way to be virtuous.’ This focus on the body also provided Camus with a way to approach all of his art, by keeping it within the realm of the concrete and the particular:

I don’t know who said that to be a good director you have to “know the weight of the scenery with your arms,” but it’s a great rule in art. And I love this profession which obliges me to consider simultaneously the psychology of personalities, the placing of a lamp or a pot of geraniums, the texture of a cloth, the weight and counterweight of a heavy piece that must be flown around the stage. . . . Isn’t that the very definition of art? Not reality alone, nor imagination alone, but imagination taking flight from reality.

In this, Camus subsumes his other writing (fiction and essays) to the primary importance of the theatre: ‘I even feel that the moment I consent to be a writer only, I shall stop writing. And where the theatre is concerned, the reconciliation is complete; to me the theatre is the highest of literary forms, and certainly the most universal.’

At the end of his life, Camus was about to be given his own theatre in Paris, as part of Andre Malraux’s national cultural scheme, in which Camus planned to explore full-time his ideas regarding stage and performance. His essay, “Why I Work in the Theatre”, was, in many respects, a preparation for this possibility; an attempt at reorienting his public image.

4.

So Camus began and ended his literary career in the theatre, and it was a continuous touchstone for his creativity during the years when his novels and essays brought him greater public acclaim. From this, I would argue that Camus’ understanding of the theatre grounds his literary imagination, and underlies all of his novels and essays. In the Théâtre du Travail, for example, Camus produced Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound (also adapted by Camus) and Pushkin’s Don Juan. Don Juan soon after appeared in Sisyphus as a sketch of an absurd man, and Prometheus is also introduced in that work as a figure of revolt. Afterward, the myth of Prometheus underpinned the second cycle of Camus’ work, just as the myth of Sisyphus underpinned the first. To adapt, direct, or act in such plays, provides a person with a unique perspective on a particular type of character; one based, not in some disembodied concept, standing on the outside and looking in at such a character, but an understanding enacted in and through the body, standing on the inside and looking out.

It was this perspective that Camus carried over into his literary essays. It was, for example, against the background of his working in the theatre in Algeria in the 1930s, that he produced his first two collections of lyrical essays, and first wrote A Happy Death. One of the significant steps he took in reconfiguring A Happy Death into The Stranger was when he ditched the third person narrative and replaced it with the more dramatic first person monologue of Meursault. It was a narrative perspective which he later adopted in his final published novel, The Fall – although it was a very different style of first person narrator – so much so that Camus himself recorded a reading of that novel for the radio, as a series of dramatic monologues.

It was this theatrical imagination which, between 1941 and 1947, Camus brought to bear upon what would be his second published novel. The Plague, moreover, was composed in the Five Act structure of classical theatre where, as Camus was fully aware – and which he tried to make us aware also – the body is always centre stage, and almost always under threat.