A pre-history of Australia’s two-party system

And another political paradigm that still remains a viable alternative

1.

The recent federal election here in Australia was a reminder that traditional electoral politics in this country is a contest between two paradigms. The still-dominant paradigm is that of the two-party system, but that is increasingly coming into conflict with another paradigm, a largely hidden ground that surfaces in the figures of independent candidates. This was very much part of the recent election, in the form of the so-called ‘teal independents’, the electoral success of whom contributed to unseating the government; although there are more traditional independents, such as Tasmania’s Andrew Wilkie, who has held his seat since 2010. In between these two paradigms, there is a mixture of minor parties and ‘networks’ associated with particular outsized personalities: attempting the best of both worlds, being neither party nor independent, but ending up suffering the limitations of each. The minor parties, on the other hand, seem to understand the problems with the party system, but fail to see that problem is also with a party system; they recognise the problems with the dominant paradigm, but they can’t think or act beyond it, thus maintaining the status quo.

What all of this misses is that this other paradigm is not only the historically prior system, but it is also the one most consistent with Australia’s constitutional structure. This is the primary paradigm. The two-party system, although dominant, is a later bolt-on, grafted to our system of government and held there by convention, and reinforced by an incurious media. This is the secondary paradigm. The retrieval of the primary paradigm – led by an increase in independent candidates and members of parliament – is, in many respects, closer to the centre of gravity of Australia’s constitutional structure. It is certainly closer to what the architects of that structure had in mind when they convened a number of constitutional conventions during the 1890s, prior to Federation on January 1, 1901.

2.

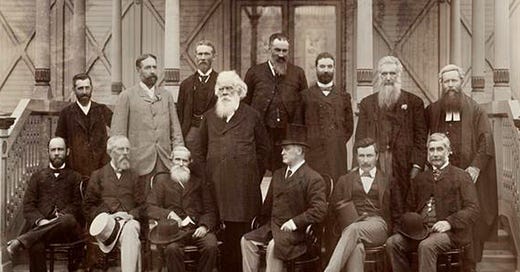

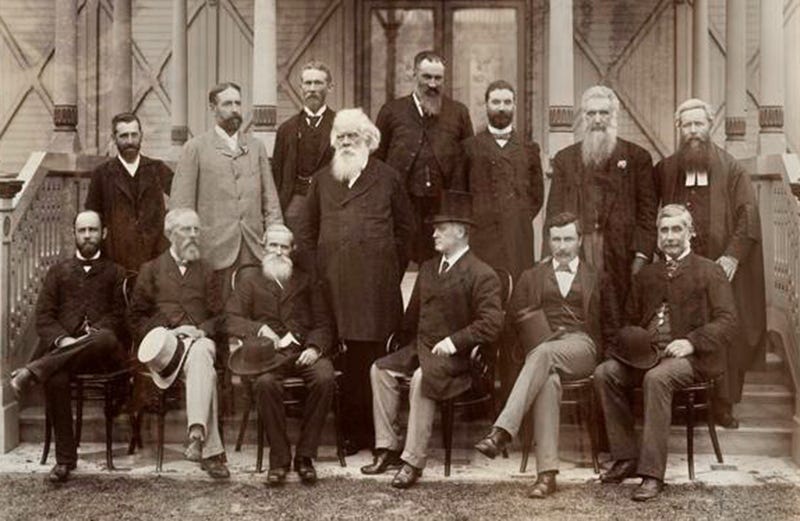

The seed was sown in the first Conference in Melbourne, 1890. On Tuesday, February 11, Andrew Inglis Clark – who wrote the first draft of the Constitution – interjected into a general discussion about existing constitutional forms in Britain and the United States of America.

‘Party Government is played out,’ he said.

‘But,’ responded Dr John Alexander Cockburn, ‘party government obtains to the fullest extent in America.’

‘Nowhere more so,’ added Alfred Deakin (who would, in 1903, become Australia’s second prime minister).

The following year, at the National Australasian Convention Debates in Sydney, Clark clarified his earlier point, by referring to a speech made by Chief Justice Higinbotham, in the colonial Legislative Assembly of Victoria, which Clark cited from Hansard. ‘Whenever this question of responsible government crops up,’ Clark said, ‘I think immediately of a passage in [Higinbotham’s speech], with which I am so familiar that I can always go at once to Hansard and pick it out. It reads as follows [citing Higinbotham]:-

“I do not know whether hon. members have observed it; but it ought to be observed, that there are many persons now in this country who have even begun to question the foundations of our Constitution – to ask, “What is the use of responsible government; what good can possibly come out of this House?” These feelings of distrust and disapproval are, if I do not mistake, almost entirely occasioned and generated by the accursed system under which the party on this side of the House are always striving to murder the reputations of the party on the other side, in order to leap over the dead bodies of their reputations on to the seats in the Treasury bench….”’

‘What about the language of parties in America?’ asked Deakin.

‘If the hon. gentleman wishes me to diverge at this moment,’ said Clark, ‘I will answer him, and say that party government is just as strong in America as it is in the Australian colonies, or in England.’

To which Deakin replied: ‘Without responsible government!’

On Friday, March 14, 1891, Sir Henry Parkes weighed into the discussion by citing British parliamentarian, William Gladstone. But he was careful to preface his comments by referring to Gladstone’s parliamentary experience rather than his party affiliations. ‘I am not referring to Mr. Gladstone as a party leader,’ he said. ‘I am not seeking to use his authority as that of a party leader; but I use his authority as that of a man who has been close upon sixty years in the House of Commons.’ He goes on to say: ‘Well, Mr. Gladstone has described what the English Constitution is:

“More, it must be admitted, than any other, it leaves open doors which lead into blind alleys, for it presumes more boldly than any other the good sense and the good faith of those who work it.”

‘The success of any constitution framed by man, the success of every constitution, call it what you may, must depend upon the good sense, self-restraint, and good faith of those who work it. [Gladstone] goes on:

“If, unhappily, these personages meet together on the great arena of a nation's fortunes, as jockeys meet upon a racecourse, each to urge to the uttermost, as against the others, the power of the animal he rides; or as counsel in a court, each to procure the victory for his client, without respect to any other interest or right, then this boasted Constitution of ours is neither more nor less than a heap of absurdities.”

‘How true it is!’

On Tuesday, March 17, Sir Samuel Griffith, in a discussion on the separation of the upper and lower house, argued that the delegates should keep in their minds the necessary distinction between constitutional government, responsible government, and party government. ‘It is absolutely impossible to frame a constitution that will not allow of conflict between two houses,’ he said. ‘Every constitutional government consists of two or more parts, each one of which can put the machine out of gear. That is the essence of constitutional government. The only means of avoiding collision is to have autocracy. Constitutional government includes a great many forms. Any sort of government in which different bodies act as a check on others is constitutional government. Constitutional government is not by any means the same as responsible government, and responsible government is quite a different thing from party government. Constitutional government simply means the existence of the checks of the different bodies on one another. Responsible government practically has come to mean a government which is turned out of office when it does not command the support of the legislature; and party government is a thing of which we have had some experience in Australia, but which I am afraid is becoming somewhat discredited’ (emphasis added).

Later that same day, Richard Chaffey Baker repeated this distinction between responsible and party government. ‘The ministries nowadays are appointed nominally by the Crown,’ he said, ‘but we all know that they are really chosen by one branch of the legislature, and why is it impossible to work out the representative form of government by both branches of the legislature directly choosing the executive, who will be responsible to them, and who will not be turned out at a moment's notice on some party question? Has this system of party government worked so well that we cannot improve upon it?’ He added: ‘I, for one, think that half of the time of parliament and the ministry is taken up by the quarrels between the “ins” and the “outs”; and if anything could do away with that state of affairs – if ministries were enabled to devote the whole of their time and attention to carrying on the business of the country, and the framing of wise measures, if they were not obliged to fight day after day simply to retain their seats, and were not obliged to bring in measures which they would not have brought in were it not for party purposes – the people would be much better satisfied with that form of executive than with the form under which we now live.’

‘That could be done by abolishing the “outs”!’ suggested Duncan Gilles.

‘Well,’ replied Baker, ‘if the hon. gentleman was one of the “outs” he would not like to be abolished.’

For the sake of brevity, I will only cite a sample of the arguments presented at the subsequent three National Australasian Convention Debates. At the first session, in Adelaide, 1897, on Tuesday March 23, Sir Richard Barker questioned if party government were at all compatible with a federal constitution: ‘Can a system of government in which one branch of the Legislature, which is supposed to represent the rights of the State, is nominated by a successful partisan leader be a true Federation?’

On Monday, March 29, Dr Cockburn reiterated the need to distinguish between responsible and party governments, arguing that the difficulty of creating a responsible government within a federal constitutional framework is best overcome by discarding party government. ‘We should depart no more than is absolutely necessary from our old traditions,’ he said, ‘though the departure must in many respects be a radical one. I think there has been a good deal of confusion with regard to responsible government under Federation. Now, I think we should draw a distinction between party government and responsible government. The hon. member, Mr. Dobson, declaimed against the evils of party government as inseparably connected with responsible government; but I would ask hon. members to turn to America, where there is no responsible government, and yet party government has there developed in greater evils than are known in England, where responsible government exists. We should not have party government, but at the same time we ought not to do away with responsible government; although, on the other hand, we should have to do away with the Cabinet system, which makes Ministers responsible to the Cabinet instead of to their real masters – Parliament.’

At the second session, held in Sydney, 1897, on Wednesday 15 September, Joseph Hector Carruthers, pointed out the problems with general elections when they are pressed into the service of party government. ‘At a general election the issues will always be clouded,’ he said: ‘Party conflicts occur, and in many cases men, not measures, are considered. In our local contests, and I dare say the delegates from all the colonies will concur in what I say in this respect, men are returned, not so much on account of the measures they support, as on account of their personal popularity.’ He added, perhaps optimistically: ‘When the press and the statesmen of the colonies have had full opportunity to shed light on the question to the people, when the fairest and fullest discussion and utmost deliberation have taken place, then the people themselves will have the opportunity to express their opinion on that one question without the distracting influences of party politics or of personalities’ (emphasis added).

This argument was reinforced at the final session, in Melbourne, 1898, when, on Thursday March 10, Bernhard Wise spoke, citing an American book popular amongst the Australian constitutional delegates at that time, called Direct Legislation by the People (1892) by Nathan Cree: ‘Mr. Cree, after speaking of the corruption and tyranny of the party machinery, and the inability of the individual voter to make his will felt in consequence of the tyranny, proceeds:-

“Party government means supremacy of party leaders. In those leaders is practically vested the power to subjugate all the official agencies of the State to their will, so that such will becomes that of the State, and government by the people is only a fiction instead of a fact. The leaders of parties frame all political issues, declare all party policies, name all candidates for office, and the electors but choose between the rival organizations. But that is no more than a power to say to which oligarchy of managers or “bosses” they will confide the control of the State.

“Under such a system the party leaders do not need to consider public opinion, further than its approval or consent may be necessary to secure the adoption of their avowed purposes, and the election of themselves to power. But great and important as is this power of ratification or rejection of party programmes and party leaders, on the part of the voters, it leaves them without any real positive political initiative, and limits them to a sort of negative action.”’

3.

Such non-party spirit amongst the delegates spilled over into the proceedings of the constitutional conventions themselves. During the National Australasian Convention Debates, held in Sydney, 1891, Thomas Playford stated: ‘I trust that we shall endeavour to separate it [the question of federation] distinctly from party politics. I can say for the opposition in South Australia, and for the ministry and their supporters, that that is what we intend to do. We intend to keep the question of federation altogether distinct and separate from questions of party politics.’ Henceforth, all conventions attempted to operate outside of colonial party influence. The People's Federal Convention, held in Bathurst, 1896, for example, was declared ‘a People’s Convention divested of all political or party significance; in fact, the spontaneous effort of a people crying aloud for more light, and refusing to rest until it was granted — a People's Convention knowing no party, favouring no sect, having for its goal the attainment of an organisation of unity and coherence, the lack of which is a source of weakness –’

The main concern with the influence of party government – during the conventions themselves, but also within the proposed federal constitution – was the incompatibility between party government and responsible government. A party politician is responsible, first and foremost, to their party, and in practice they avoid being held responsible to the parliament, housed as it otherwise is by members who are, in turn, responsible mainly to the opposing party. The governing party is therefore ruling mainly on behalf of their own interests and not in the interest of the whole; this state of affairs is thereby incompatible with the idea of a federation, which thus makes of the constitution a ‘heap of absurdities.’ These concerns are more remarkable if it is kept in mind that most of the delegates were themselves members of parties within the colonial parliaments. In this, they wanted the federal parliament – which was ideally to be elevated above each and all of the proposed state parliaments – to also exercise a more elevated form of politics; a model perhaps for the reformation of each of the colonial parliaments maturation into state parliaments within the federal system.

It would be inaccurate, however, to give the impression that this position was the only one put forth during the conferences. There was an opposing view, which now needs to be considered. Regardless of whether they agreed or not with the arguments levelled against the idea of party government, this group of individuals adopted the position that political parties in practice are inevitable and to argue otherwise is unrealistic. This may be seen as an early version of the contemporary view that politics in Australia is party politics, and anything else is unthinkable.

This view was raised as early as the Australasian Federation Conference, in Melbourne 1890. On Wednesday, February 12, Mr McMillan stated: ‘We all belong to Parliaments in which there is party government; we know that, no matter what may be the sentiments in connexion with federation, party purposes will come in and party antagonisms will be aroused.’

At the Australasian Convention Debates, in Sydney 1891, on Tuesday, March 17, John Macrossan said: ‘Do not let us forget the action of party. We have been arguing all through as if party government were to cease immediately we adopt the new constitution. Now, I really do not see how that is to be brought about. The influence of party will remain much the same as it is now, and instead of members of the senate voting, as has been suggested, as states, they will vote as members of parties to which they will belong. I think, therefore, that the idea of the larger states being overpowered by the voting of the states might very well be abandoned; the system has not been found to have that effect in other federal constitutions. Parties have always existed, and will continue to exist where free men give free expression to their opinions.’

On Thursday March 25, 1897, at the first session of the National Australasian Convention Debates, Josiah Symon made the same point. ‘I am myself for responsible government,’ he said: ‘I wish to cling to the English model wherever I can. It is the freest government under the sun, and try as we may, and animated as we are by a federal spirit or by a spirit of compromise, you cannot eradicate party spirit or government by party in these days from the political life of the British race. It is a system with which we have grown up.’ The following week, on Tuesday March 30, Edmund Barton repeated this view: ‘I think it was Mr. Symon who in his able speech laid down that you cannot do away with that ideal and that form of political life which centuries of development have given to those who live under the British Constitution, a development which was moulded by their fathers; and if you import anything like the Swiss or the United States Constitution into ours you would not be able to do away with party government, because the conditions under which you live would assert themselves.’

But of all the critics of the view that party government must be separated from the workings of responsible government, the most vocal, and the most adamant critic, was Alfred Deakin. ‘The influence of party government upon the working of our institutions was first indicated by the late Mr. Macrossan in 1891,’ he said at the first session of the National Australasian Convention Debates, in Adelaide 1897, Monday, March 29: ‘It is a most fruitful influence hitherto ignored in this debate, and to which I shall recur. I am perfectly aware, as Mr. Dobson reminded us, that responsible government, as we use it, may not be theoretically perfect as a form, nor may it effectually prohibit the manifestations of human nature-political human nature especially-as we are more or less acquainted with it. Apparently, because that hon. gentleman has seen party spirit degraded to small and petty things, he would contend that what we need is a mere change in its form. I would venture to reply that no change of form known to us, and no form I am acquainted with in the civilised or uncivilised world, can confine, or is capable of seriously altering, the political spirit under which the inhabitants elect to work it.’ But Deakin’s arguments are not so much concerned with responsible government. Instead, they are more tightly focused on ensuring the co-working of constitutional government – in particular, the separation of an upper and lower house – with the federal need to protect state rights.

On Monday September 20, 1897, at the second session of the National Australasian Convention Debates, Deakin makes the following case, regarding the need to mitigate the deleterious effects of deadlocks. ‘Under those circumstances you can have no deadlocks under this constitution unless you have one party dominant in the one chamber, and the other party dominant in the other,’ he said: ‘Under no circumstances will it be a struggle, as the hon. member put it, of house against house – using those terms strictly – but it may well be a struggle of the majority of one party in one house against the majority of another party in the other house. Under those circumstances – the questions being rarely state questions – the questions being party questions – the struggle being of one party in the country as a whole, against the other, each party having its representation in both houses, and each party’s aim being to have that majority in both houses which will enable it to control the policy of the whole country according to the principles of that party, it appears to me that deadlocks are less likely to occur in this constitution than in any federal constitution the world has yet seen.’

The argument regarding the protection of state rights, which he repeated often, was raised, for example, during the first session of the National Australasian Convention Debates, in Adelaide 1897. On Monday, March 29, Deakin said: ‘We shall have party government and party contests in which the alliances will be among men of similar opinions, and will be in no way influenced by their residence in one State or another... When we have adopted responsible government, we have necessarily adopted party government, and we have to be guided by experience as to how it works. It may be hard to prophesy what all the results will be, but, though neither a prophet nor the son of a prophet, no man need fear that whatever political struggles arise will very rarely indeed, even remotely, relate to State rights or interests.’

4.

These arguments in favour of party government, however, do not survive scrutiny. The initial reaction of some of the delegates, as we have seen, was to fall back on stating that this is just the way it is, always has been, and so always will be. Macrossan said that ‘Parties have always existed, and will continue to exist where free men give free expression to their opinions’ (emphasis added); while Barton said ‘you cannot do away with that ideal and that form of political life which centuries of development have given to those who live under the British Constitution’ (emphasis added).

Party organisations, in the sense understood by the delegates, however, were only a recent development in British political history. Forming in response to the 1832 Reform Act, and expanded by the further Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884, when the franchise was initially granted and then extended, the Commons was not so much occupied by Parties, as by loose factions, organised around personalities instead of principles, and the self-interest of its members rather than broader political responsibility to an electorate. It emerged in unison with the idea of responsible government, which the wider franchise forced upon the Commons, not in order to facilitate its progress, but rather to exert control over its direction, to mobilise and direct newly minted voters. John Gordon, during the first session of the Convention Debates, held in Adelaide, on Monday March 29, 1897, was thus correct in stating – after pointing out that the Parliamentary Commission in New Zealand ‘absolutely condemns party government’ – that ‘Responsible government is on its trial. It is not ancient. It has really sprung into force within the lives of our grandfathers.’

In the ‘centuries of development’ (Barton) under the British constitution, the emergence of political parties could be perhaps seen as a stage between the earlier, pre-democratic, pre-nation-state, aristocratic form of government, and the burgeoning responsible form of government within young representative nation-states. To carry such aristocratic pretensions into the modern world leads less to democracy and more to variegated forms of oligarchy. Already we have heard from Sir Samuel Griffith on the question of deadlocks: ‘That is the essence of constitutional government,’ he said: ‘The only means of avoiding collision is to have autocracy’ (emphasis added, Tuesday, March 17, 1891). A point taken up also by Wise during the third session of the Convention Debates, on Thursday, 10th March, 1898: ‘The view I take is that we must run the risk, and ought to run the risk, of dead-locks. It is a trite saying, but it is none the less true, and deserves to be repeated in this connexion, that there is only one form of government in which a dead-lock is impossible, and that form of government is where the ruler is a despot. Dead-locks are the price we pay for constitutional liberty’ (emphasis added).

Twelve years after the first federal election, in 1912, Wise reflected on the heated debates at the Constitutional Conventions on the topic of deadlocks and he wondered what all the fuss was about. After four successive terms, no such deadlocks had occurred. But he spoke too soon. The next year, in 1914, a deadlock occurred; there has been another five since. What is initially striking here is that no deadlocks occurred during the first four parliamentary terms, between 1901 and 1913. Three of these terms operated outside of the current two-party system (although in the presence of political parties). The fusion between non-Labor parties in June 1909 precipitated the 1910 federal election. Then a deadlock in 1914, during the first year of the fifth parliamentary term, resulted in our first double-dissolution election. Such deadlocks have occurred since because of party conflict, not in spite of them. Moreover, the presence of the same parties across both houses has in practice effectively reduced the distance that should constitutionally exist between them. A prospect which led Charles Kingston, during the conventions to respond to Deakin by saying: ‘The country might say, “a plague on both your houses!”’ (Monday 20 September, 1897).

This inflation of party government at a federal level, however, has certainly removed the other of Deakin’s fears: that one or two of the larger states would join forces and overpower the state rights of the remainder of the federation. Little conflict exists between the states, it is true, but what has resulted is an increased conflict between the federal government and the states, which has, if anything, aggravated a situation which Deakin hoped to obviate. In practice, it seems, the form of party government that Deakin and others promoted has been the instigator, rather than the alleviator, of the woes that may befall a federal constitutional framework that is striving also for responsible government. ‘You may go “like a crab, backwards,”’ said Henry Dobson to Deakin (Monday March 29, 1897).

5.

So what went wrong? There were two factors at play during the constitutional conventions during the 1890s which resulted in the unintended consequence of producing party government within the federal parliament, despite the constitution being written and implemented in their absence. The first factor was the inability of the delegates to come to a consensus on questions of finance and taxation. It seems the desire to not arouse party feeling during the conventions – perhaps the best place to air these questions and seek resolution – resulted in these questions being left for the first federal parliament. That the resulting factional divisions between free trade and protectionist advocates among the states may have been unintended, they were certainly not unexpected. This point was made during the first session of the Convention Debates, in Adelaide 1897, on Friday March 26, by Dobson: ‘When you take the risk of engrafting the principle of responsible government upon a Federated Government, think of what you are doing. Federal Government will have eliminated from it almost every party question except taxation, and when once you decide to give over to the Federal Government sufficient revenue for its needs its right to levy taxation will not be enforced once in a generation, and the great cause of party strife – taxation – will then be removed. But if the Cabinet system is adopted you will absolutely be inviting the members of the Federal Parliament to turn themselves into party politicians the moment they enter the floor of the House; you will invite them to create party objects, and to make party strife; you will invite them to look with envy upon the first men who sit on the Treasury Benches; and they will set to work at their caucus meetings to see not what is best for united Australia, but with what little game and plan they can knock Ministers off the Treasury benches. For these reasons I believe this topic is about the most important which will engage the thoughts of the members of this Convention.’

It was a point Dobson repeated during the second session, but to no avail: ‘Although I am one of those who think with Sir Samuel Griffith, and to a very great extent, in fact, entirely, with you, sir, in believing that federation will develop a better form of government than our party and responsible government, and believing as I do that there is not the same room in the federal parliament for party politicians as there is in the state parliaments, I am bound to face this fact, that we shall have the party politician on this everlasting question of free-trade and protection, a leading feature in the federal parliament the moment its doors are open. But if you leave the whole financial problem to the federal parliament you will create party electorates and party would-be politicians before the doors of the federal parliament are open’ (Wednesday 8 September, 1897).

The second factor at play during the conventions was the exclusion of delegates from the recently formed Australian Labor Party from participating. The irony of this move is that one of the platforms that the nascent Labor Party was pushing at the federal level was the election of ministers to ensure the existence of non-party government. This exclusion did not extend, however, to the elections of the first federal parliament. As Dobson predicted, this included factions of free-trade and protectionists; but as was perhaps not predicted (certainly not by Deakin), this also included elected members of the Labor Party. Although the Labor Party had earlier instigated a solidarity pledge, it was not initially signed by all of those members pursuing a labour platform. But as the first few years of federation passed, such solidarity – the origins of the current notion of party discipline – became seen as essential for parliamentary success. This led to the first national labour government in the world, when Chris Watson became Prime Minister in 1904. It was in order to offset such parliamentary strength that led to the free-trade and protectionist factions to fuse together to create an opposing party. So by 1909 – and against the spirit of constitutional and responsible government – the current two-party system emerged.

Does the fact that the emergence of the two-party system can be traced back to certain ironies or failures of the constitutional conventions in any way invalidate the arguments against party government presented at those same conventions? On the contrary, these failures can themselves be traced back to the factional and party biases of the colonies which the conventions attempted, and not entirely succeeded, to raise itself above. Even if balanced against the successes of pulling off an enormously difficult task of creating a framework for the federation of disparate colonies, these failures cannot be overlooked. They are perhaps the first example to evidence the force of the arguments presented against party government.

As early as the National Australasian Convention Debates, in Sydney 1891, Colonel Smith said: ‘We were told by the hon. member, Mr. Deakin, that the dominion must be established on the old and broad lines of the English Constitution, that we must have party in the dominion just the same as we have party in the different colonies. Now, I think it worthwhile considering whether we should not adopt some modification of the party system of government. . . Why should we have party government in the dominion parliament?. . . I do not see the slightest necessity for creating two hostile parties in the dominion parliament. We look to that body to exercise cool, calm, and deliberate judgment on every public question coming before it, and we should not so constitute it that its time would be occupied in fighting about who should be in office and who should not. As far as the dominion parliament is concerned, I think the system of party fighting might be obviated’ (Monday 9 March, 1891).

On Friday, March 26, 1897, Dobson said – in a statement as true today as it was well over a century ago: ‘We have heard a great deal – and I am glad of it, because it shows how proud we are of the representative institutions of Great Britain – of the advantages of responsible government and the party system, but have not we all felt at times ashamed of the party system, and a little ashamed of ourselves, too. According to my hon. friend on my right, we are covered with shame all round, and that is just what I want to bring this Convention to. You may be proud of representative institutions, but there are times when we may well feel ashamed of some aspects of them, and I want to save our grand Federal Government from the evils that attend our party systems, and to keep it free from them so, that you may admire, esteem, and respect it, and so that no man shall be able to say of it what I have had the temerity to say of our governments by party. If some of the defenders of party government only had an insight into the methods taken by caucuses to hinder and to overthrow the Government of the day, or to form policies, their respect for this grand institution would be considerably diminished. I think I have used strong arguments to prove that we should avoid having government by party.’

6.

One of the main reasons that many of the delegates during the 1890s argued against party government is because they had the advantage of being able to draw upon the practical examples of party governments in both Britain and the United States. What is interesting here is that in these countries party government formed through force of circumstance and without prior planning or models to imitate; before these examples, no such party system existed. They had no precedent to judge their endeavours in advance and this couched their emergence in an air of inevitability. Australia was in a unique position at that time to have such examples to draw upon – to learn from the mistakes of others. This allowed a more detached view of the history of other countries’ political development. Australians were able to ascertain that the emergence of party government was not an inevitable or necessary process, and that they did not share the same circumstances as other countries in which such party government existed. Australia also had its own short history of colonial factionalism to examine and the foresight to seek a change of direction, before it was too late.

After more than one hundred years of the two-party system in Australia we have largely lost this critical remove, even if we now have a hundred years of political history to measure against the arguments and predictions made at the constitutional conventions. Have they come to pass? By and large, they have. In July 2009 – during the centenary year of the two-party system in Australia – longstanding Clerk of the Federal Senate, Harry Evans (now retired), presented a Senate Occasional Lecture on the changes to federal parliament over the previous forty years of his career. What is interesting about this lecture is that what Evans highlights as ‘significant failures to change or changes for the worse’ are exactly those aspects that the federation convention delegates warned against over a century earlier. ‘We do not have,’ said Evans, ‘a public appreciation of the distinction between Parliament and government, legislature and executive. Australians still think of government and parliament as one and the same thing, as well they might given the rigidity of executive control of lower houses, and independent upper houses are still seen as something of an anomaly’ (emphasis added). In other words, Australians today do not distinguish between parliamentary and party government (‘one and the same thing’), and constitutional government (‘something of an anomaly’).

The failure for this, and for the diminished functioning of our constitutional and parliamentary forms of government, according to Evans, is the role played by party government: ‘Party discipline, which is the foundation of executive control of lower houses, is stronger than ever. If anything, it has been strengthened by the new techniques of spin doctoring and news management that governments have perfected. . . . Apart from party discipline, the trends of modern politics have greatly strengthened the central power within parties in government. The PMO [Prime Minister’s Office], not the Cabinet, is now the supreme governing authority of the country, and seems to have greater power than some ministers. We still have one of the weakest legislatures of the democratic world, especially compared with our great and powerful friends. The Parliament here is under a degree of executive domination that would not be tolerated elsewhere, even at Westminster.’

What Evans is pointing to is the false conflation between the two political paradigms, the submergence of the primary paradigm beneath the two-party system. We can see this occurring even in the language we use describe politics in this country, to keep us focused narrowly on the two-party system as the medium through which to understand and think about politics, rather than to allow us to think through the possibilities of the primary paradigm submerged beneath. Let’s consider here only two.

At each federal election there is some concern that neither of the two major parties may get a majority of the seats, and so we are told that we risk a ‘hung parliament’. But this phrase has no corollary in the real world. After each federal election the parliament always retains its capacity to function, the seats still work for sitting on and the chamber still works for deliberation. It remains always ready to be activated by the will and imagination of all elected members. In the circumstance of a major party not getting a majority of seats then what does not retain its ability to function is the two-party system, with the members of each party unwilling to enter parliament and make an argument without the outcome being known in advance. It would be more accurate to refer to such a situation as a ‘hung party system’. What the more conventional phrase does is deflect a fault of the party system onto the parliament, and unjustly so.

The second example is the use of the term ‘Independent’ to refer to a politician or candidate who is not affiliated with a political party. This term distorts our understanding of political reality in two ways. Firstly, it defines such figures against the two-party system, assuming that system to be central and these figures as the anomaly. But, as we’ve already seen, it is the paradigm that these figures are trying to retrieve that is primary and the two-party system that is the anomaly. Secondly, the term ‘Independent’ erroneously describes the situation of such figures, who are, perhaps more so than their party counterparts, entirely dependent on their electorates. Furthermore, without the veil of party politics to protect them, they are, at the same time, more nakedly responsible to parliament. Such figures are, if anything, interdependently situated between parliament and electorate, and transparently accountable to both. There is little or nothing independent about these roles. Once more, the use of this term deflects from the faults inherent in the party system itself: for it is, if anything, the party system that seeks to operate as independently from the parliamentary and constitutional system as possible, and to avoid, where it can, their responsibility to parliament – and ultimately, their responsibility to the electorate.

What Harry Evans said in his Senate Occasional Lecture is simply echoing what the delegates of the federation conventions argued more than a hundred years ago. It is a message that has only grown in importance since. What does it require to be heard? ‘Reform of political parties,’ Evans suggests, ‘would be more likely to lead to a better functioning Parliament. That, however, would be a really difficult reform.’

Difficult, yes. But not impossible.

I am currently deep into the writing of an unintentionally long book and so have not been able to afford the time to write as much as I’d like for this newsletter. That said, I have various notes and pieces in various states of near completion which I’d like to be able to work on and post here – for example, on Albert Camus and democracy, on the radical misunderstandings of Hannah Arendt, Northrop Frye on reading, Durkheim and Bentham on fiction, and the most important work of political theory you’ve probably never read (and probably couldn’t even guess), and so on – so if you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship (and, yes, the use of the term ‘independent’ is accurate here), then please consider doing one of two things, or both: please consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.