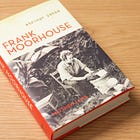

In February I gave a talk at the National Library of Australia on the topic of Frank Moorhouse’s Juvenilia. Part 1 of the text for this lecture can be found here, along with a recording of the audio that you can listen to.

But now I have to make a confession.

I knew none of that when I was writing the first volume of Frank’s biography. I knew about the Frank Moorhouse parts, of course, but I hadn’t originally considered them in relation to the broad category of juvenilia, and what he had in common with other child writers. I only discovered the field of Juvenilia Studies during the year the book was in production, being edited and printed. But I wish I had known about it sooner, because it would have saved me several years of anxiety and self-doubt as I was researching and writing it. Let me explain.

With a few exceptions, conventional literary biographies tend to pass over the childhood of their subjects quite quickly. This is usually (but not always) confined to a single, opening chapter, beginning with the birth of the subject. This includes briefly sketching who the parents were, their social background, and so on. There are a few childhood memories, a few family anecdotes, and a brief outline of any early attempts at writing – and then by chapter two, we’re launched into the more important adult world of the subject.

In contrast, my book spends four chapters examining the first 21 years of Frank’s life. And even then, I had to cut out half of what I had written before publication. There is a particular sense of dread that comes from knowing your publisher wants your subject’s life story told in 150,000 words, that you have written 80,000 words – which seems like progress – and yet you realise that at this stage in your writing your subject is still only 17 years old – and there is still 65 years of their life to write about. I’m sure there’s a German word for it.

I said at the beginning that there are two reasons why I have chosen this topic for tonight’s talk. The first reason is because the National Library holds the early Papers of Frank Moorhouse. But the second reason is to establish a public justification for why I spent an inordinate amount of time researching and writing about this early period of Frank’s life – and why I took seriously what he wrote during this period, as seriously as I took what he wrote later in his life, when he was an adult and a published author. Juvenilia Studies provides me with a post-hoc rationalization for doing so. But it also provides strategic cover for explaining why I actually did.

When I first went through Frank’s archives – even when looking chronologically beyond this early period, past the age of 21 - there were two sets of questions which kept coming to the foreground, which forced me to return to this early period of his life, time and again. To keep going back over it - broadening the scope, and deepening the inquiry.

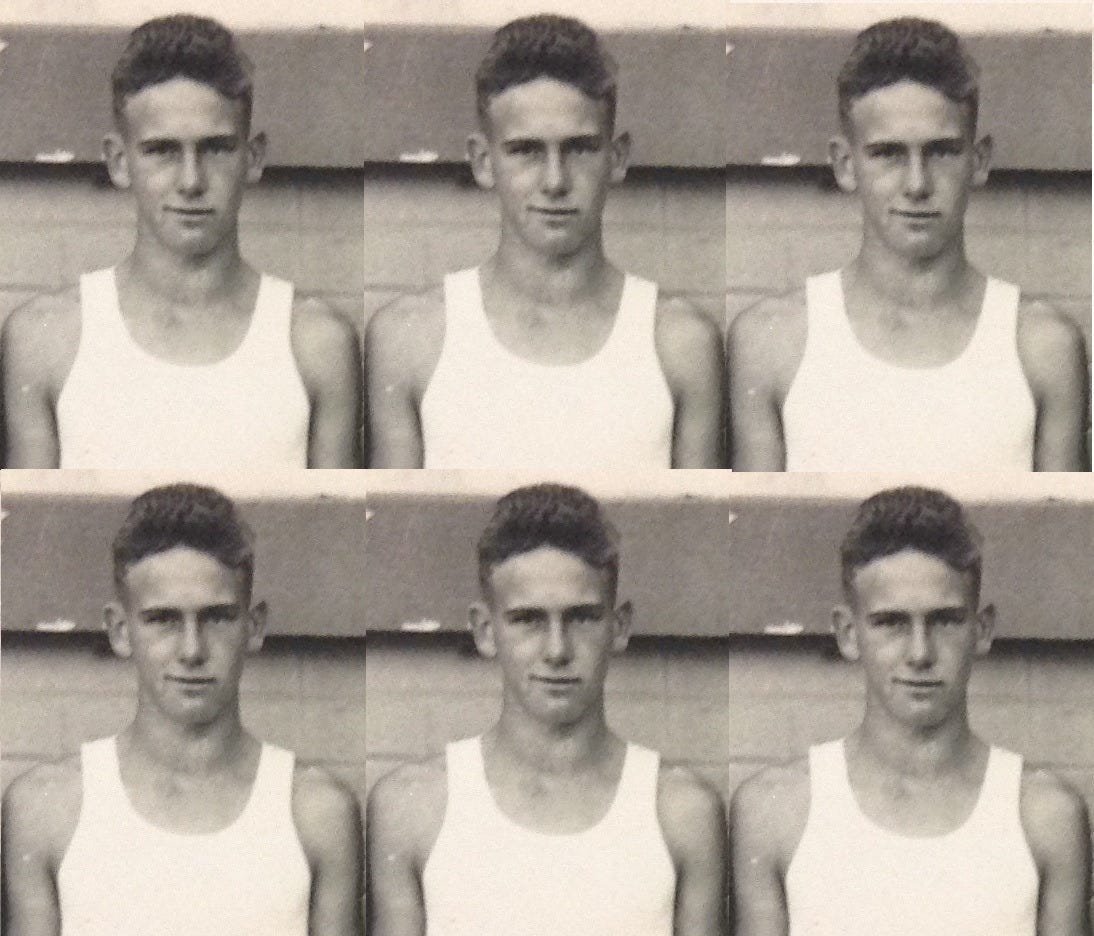

So, first off: We all know that Frank spent much of his adult, public life arguing against censorship, arguing in favour of free expression, and exemplifying the life of a writer in constant renegotiation with the conventions of their own society. One of the purposes a literary biography should be to map a writer’s intellectual development. But the problem was that Frank already held these views as an adolescent. It is as if, in this regard, Frank was fully formed.

We’ve already seen some examples of this. But take, as one more example, the letter he wrote in his application to various Sydney newspapers to become a copyboy. One of the reasons he wants to be a writer is, I quote: ‘My wish to see the world a free and a just place not a world of propaganda, lies, censorship, and bias.’

That’s Frank at 16.

But, of course, Frank was not fully formed. And so the question became: how did a 16 year old school boy in regional Australia in the 1950s come to these intellectual positions in the first place. This demanded more attention to this early period, not less. It called for closer scrutiny to Frank’s intellectual environment – the books and periodicals he was reading – but also closer examination of what he was writing, during this period.

For example – and this is just one of many examples - Frank’s father read The Free Spirit – which contained articles about the conflict between freedom and authority – and he read it as part of the struggle against the perceived threat of communism – and the Australian Labor Party. He gave this magazine to Frank in the hopes that it would inoculate Frank against this threat. But Frank read the same arguments in terms of freedom against parental, school, and church authority. He would then write essays and short stories that animated these ideas, but filtered through his own experience.

Tracing this process necessitated a closer look at what Frank was writing during this period – his juvenilia. But doing so revealed something that I thought was interesting at the time but which the late discovery of Juvenilia Studies has made me come to think of as being even more interesting now. Adolescents tend to write unselfconsciously about their own childhood experiences, because this is the compass of all that they know. Or else they write aspirational pieces about adult characters, or how they imagine the adult world to be, and what they imagine to be their place in it: the child playacting at being an adult.

But what is remarkable about Frank’s writing in the mid-1950s is that he self-consciously takes as his subject matter the category of ‘adolescence’. He is not simply writing from the perspective of an adolescent; he is taking ‘adolescence’ itself as his object of inquiry, while at the same time contrasting it with the adult world – rather than simply trying to assimilate his writing to that world. He is, in a sense, actively trying to resist the adult world.

He writes a number of essays and short stories on various aspects of this theme. He then grouped these stories together, as if trying to put together his first collection of stories. And the title he gives this collection is: “This; the world of the adolesense [sic]”.

Towards the end of his final year of high school he then writes three essays, called: “The World and Me”, “A Ramble in the Mind of an Adolescent”, and “Rambling in the Mind of an Adolescent (Part II)”

Here Frank concedes that adolescents are inexperienced, half-educated, insensitive, and emotional (many of his stories have already explored these themes). But he demands that adults recognise the world they have created, and the mistakes they have made, socially and politically, which will be inherited by the younger generation.

Much of these essays are spent listing many of the contradictions that Frank sees in the modern world – the general human sufferings, such as starvation and economic insecurity, but also the lack of sexual freedom, racial freedom, and intellectual freedom.

At the heart of this is a question that concerns Frank the most – I quote: ‘Wouldn’t Humans work together and understand each other better if we expressed our true selves and not the special convention-erected self with which we are all burdened?’

In a very real sense, this is, for Frank, the fundamental question, that he kept raising, again and again, in everything he wrote, for the remainder of his life. This is the question, for example, Ambrose sparks in Edith Campbell Berry.

But staying with the 1950s: If we pull back and put all of this in a broader historical context, what Frank is picking up on is a very real social and cultural shift. This is the period that a new social category emerges, that of the “teenager”. This was brought about through a post-war prosperity, which allowed for an extension of childhood, and a delaying of adulthood. By choosing to complete high school, Frank was choosing to prolong his childhood. And he was one of an increasing number of young people to do so in the mid- to late-1950s. Many went on to university, which prolonged this further. This meant that adolescents were, to a greater degree than the previous generation, kept out of the adult workforce, they had more leisure time, and they had more education, and so more time to learn about the world they were inheriting before having to fully enter into it – and this also means more time to become critical of the world around them. This was the situation of the ‘teenager’. And it was reinforced, and to an enormous degree, facilitated by an expanding commercial and media culture. Television, cinema, rock’n’roll music, fashion and various styles of living – most of it being directly imported from the United States of America.

What is remarkable about this, is not just that Frank was able to think and write about this cultural shift, as it was happening, but he was able to do so, while he was himself undergoing it; that is, while he was himself being a teenager.

In his final year of high school, while writing these essays, he put his earlier short stories aside and begins to write a novel. Again, he takes ‘adolescence’ as his subject matter. And when he finishes, he writes a preface. I only cite part of this in the biography, so I will read the full preface here, as it sums up everything I have just tried to say. That ultimately what Frank was recognising in the 1950s – in himself, in his generation – was the seeds of disaffection that would become more prevalent in the 1960s, especially in the generation coming up under Frank.

As I read this, just note the remarkable interplay between the genuine intellectual and expressive limits of being an adolescent, together with an uncharacteristic self-awareness of those limitations, and a burning desire to transcend them.

On another level, this could perhaps be read as an informal manifesto for Juvenilia Studies:

A 17 year old Frank writes:

This story was written by me, an adolescent. It is therefore immature in both style and treatment. But on the other hand it is true and original because it is a story of adolescence from the point of an adolescent and written with an adolescent style. In fact the whole story should reek of adolescence.

I do not think adults realise the position of modern adolescents. Perhaps if any read this story they will. I think we fill the psychologists’ description reasonably well – we do become depressed we do become wildly enthusiastic over impractical schemes and we do feel very insecure at times. But in the main we are happy. We are happy when we are at our parties, at our camps, at our dances and in our discussions. It is only when we make contact with adults that we feel uneasy. I think this is becaused [sic] we think adults treats adolescences as a comedy. But it is hard to generalise. Some of us distrust adults because of the mess they have made in life; some of us worship adults because of their accomplishments; some of us do not think about it.

There is one group that recognise their own adolescence with all its stupidities but cannot adequately control themselves to prevent these stupidities manifesting in action. This group feel distrustful of adults because it fears scorn and blames adults for its position. They live in embarrassment caused by their own adolescences and by their companions’ adolescences.

But it will not be long (I hope) before we become adults and then perhaps we will laugh at the pains we suffered. Like men home from war we will remember only the happy incidents and these will grow more vivid with telling. The unhappy incidents will become vague and forgotten.

[signed] Frank Moorhouse Jnr.

But, of course, when Frank did become an adult, he did not laugh at the pains he previously suffered. He did not remember only the happy moments, and the unhappy moments did not become vague and forgotten, but rather became sores that he picked over for the remainder of his life. And this leads to the second set of questions that caused me to linger longer over this early period of Frank’s biography. And that is because throughout his life, Frank constantly referred back to this period of his childhood.

The first volume of the biography ends with the publication of Frank’s third book, The Electrical Experience, in 1974, which is set between the first and second world wars, on the NSW South Coast. In researching and writing that book Frank began thinking more and more about his childhood experiences. And making notes about them.

I will be the full consequences of this, in more detail, in volume two. But the problem I had – for volume one – was that I needed to corroborate these later statements, test these memories, confirm what he was saying in his private notes.

I wrote a piece for The Conversation on the difficulties of distinguishing between the facts and the legend of Frank’s life. That we are all unreliable narrators of our own lives. I won’t repeat my arguments from that piece, but the conclusion was that I had found that – for various reasons – Frank’s own reflections on his past could not be taken at face value. What I didn’t say in that piece was that many of these statements were regarding Frank’s childhood. And so I found I had to place more weight on what he was saying at the time – in his early fiction, his essays, his notes, his letters – that is, his juvenilia – than on what he would later claim to remember about this period.

And the points of difference proved quite significant. And so the question became, not how do Frank’s youthful works prefigure his more mature works – which is the conventional direction of biographical inquiry – but rather to what degree were Frank’s mature works based on a self-conscious reconfiguration – or the creative destruction of – his earlier works and memories. This reverses the conventional line of inquiry, and opens up a new perspective. But, in the time remaining, I can only outline a few of these.

It was is 1975 – which is also the year the second volume of Frank’s biography begins – when Frank is first approached by the National Library, to begin collecting his archive. The result – for the National Library – is the Papers of Frank Moorhouse, 1951-1970. But the after-effect of this – for Frank – was that this experience came at just the right moment, when he was already undergoing a process of re-examining his own childhood and adolescence. What the National Library provided was both a framework and an opportunity for Frank to do so more systematically. It was the act of going through and sorting his own papers that actively reshaped Frank’s literary imagination.

For Frank, this became what he would later call the ‘archival imagination’ – which structured pretty much everything he was to write for the remainder of his life – the foundation for which was this initial process of archiving his own juvenilia. So you can appreciate why this early body of work, and this period of his life, is fundamentally important, not just to the first volume of his biography, but to the second volume as well.

In fact, this ‘archival imagination’ was reinforced in the early 1980s when Frank received the Harold White Fellowship, here at the National Library. Ostensibly provided for historical research, Frank was the first fiction writer to receive the fellowship, which he used to explore the archives for traces of Australia’s involvement with the League of Nations. Where other people would go on ‘fact-finding’ missions, Frank referred to his ‘fiction-finding’ missions.

But even before then, one of the immediate outcomes in the late 1970s, for Frank in archiving his juvenilia, was that he started working on a series of stories, called “The Oral History of Childhood”. These pieces pull together a list of maxims, clichés, sayings, lore, and rote phrases used in childhood. Concerned with such topics as mechanical aptitude, pledges, vows, and the rules for passing notes, playground justice and notions of fairness, as well as the tests of childhood: tortures, jealousies, and the art of toughening up. Here Frank is both rewriting and appending his own juvenilia to create an anthropology of childhood – both the formal and informal, official and unofficial rules and rituals of growing up in Australia.

Another example: In 1980, Frank had published a book called Days of Wine and Rage, an anthology of texts drawn from his own writings, and the writings of others, from the 1970s. It was his attempt to define that decade. What is not publicly known is that straight after that book came out he pitched to his publisher another anthology, which he never finished, but which he worked on extensively. It was going to define the 1950s, pulling together contemporary texts about Australia written during that decade – the cold war, the debates over communism, the role of national service, but also the rise of the ‘teenager’, and the beginnings of American cultural and economic imperialism in Australia. In other words, everything that we just been discussing. And the anthology was to be interspersed with Frank’s own juvenilia, written during that decade.

Another example: In 1988, Frank had published the book, Forty-Seventeen. It is about various characters – including the 40 year old protagonist – looking back at their lives as 17 years olds, across different generations, and the contrasts between that early period and their later lives.

It should not surprise you, then, that two of the stories from this book are drawn almost verbatim from Frank’s archives, from the period of the 1950s. There is a story called “A Portrait of a Virgin Girl (Circa 1955)”, which is actually a selection of excerpts from letters that Frank’s high school sweetheart, Wendy Halloway, had written to Frank from Nowra, when he was a cadet journalist in Sydney. These are only slightly revised. The second story, called “The Story Not Shown”, is lifted directly from Frank’s 1957 journal, describing an evening when he and a friend visit a prostitute in Sydney’s King’s Cross – which doesn’t end well.

I could go on. The final Edith Campbell Berry book, for example, Cold Light, is set in the 1950s. Written in the early 2000s, it is grounded in the research from that uncompleted anthology of the 1950s that Frank started twenty years earlier. And, of course, one of the final books Frank was to have published, called Australia Under Surveillance, is a non-fiction work that re-litigates his positions against censorship, his argument for free-expression, and how the life of the writer should be in constant renegotiation with the conventions of their own society. The central conceit of that book being the fact that Frank had discovered a file that ASIO had started keeping on him – when he was 17 years old.

You will notice a theme recurring here.

As I am still working on volume two – and so I am still considering the consequences of Frank’s juvenilia – I have only provisional observations to offer in closing.

One aspect of Frank’s life that I didn’t have time to talk about this evening is his lifelong intellectual obsession with media and communications technology and their impact on our public culture. Once more, this is something that started in his childhood, with one of the first essays he wrote, when he was 13 years old, being on the history and impact of the printing press. In the late 1960s, even before his first book had been published, he was concerned about the impact of emerging technologies on the fate of literature. And on the infrastructure that supported literature. His famous copyright court case in the 1970s was very much concerned with these questions – the photocopy machine as forerunner of Google. In his final years, he spoke out about the impact of the internet, and on the threatening potential of Artificial Intelligence.

I’ve written about this elsewhere so I won’t belabour the point here. But one of my conclusions from that line of inquiry is that in the current moment literary biography takes on an additional purpose and responsibility, which I can only see becoming greater in the future. In reconstructing the long, slow process by which Frank developed as a writer, it has become clear that there are no shortcuts in making literature. And there are no short-cuts or substitutes for reading literature. There are no efficiencies to be gained by outsourcing our imagination to generative AI. Literary biography is a record and account of the all-too-human struggles and triumphs that go into creating works of literature; it is a testimony to the value of literary effort, and how that effort – in both writing and reading – is fundamental to the value of our public culture.

I only mention this here, because it reinforces what I have also come to see as the value in Juvenilia Studies, in inverting the negative connotations conventionally associated with such early works of our established authors. Because that literary effort – that long, slow process of becoming a writer – begins in childhood and adolescence. But more importantly, this human potential is only realised against the background of an infrastructure that supports literacy, the value of reading, and the free circulation of written materials. When we pass over an author’s juvenilia, we are also passing over those pre-conditions that made such juvenilia possible; we are taking for granted the very infrastructure that necessarily supports our literary and public culture. And, in doing so, we risk losing them. Central among this are our libraries and archives – these vital centres.

And so if literary biography is concerned with reconstructing the human effort behind our works of literature, it can’t just be the story of an individual author and their individual works – and in this, my book on Frank Moorhouse is not just a biography of a writer, it is also a biography of a reader, and of one of our more remarkable citizens – but such literary biographies also need to tell a broader story of a culture and the efforts of many individuals, and many generations of individuals, in creating, maintaining, and defending, our necessary cultural infrastructure – if only at those points of contact where it intersects with our immediate subject.

In doing so, I am only suggesting writing biography in the same way that Frank himself read biographies, in order to achieve what he called ‘the relief of biography’ which is to read literary biographies in order to remind ourselves that – and I quote from Frank – ‘we are not alone / others have gone this way before us’.

Thankyou.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter as it will allow me to write this newsletter more frequently, and pay for whiskey and books).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

Find where to buy the book here