A Substacker Reads Luiz Costa Lima in Australia and Bursts into Tears (with apologies to László F. Földényi)

On mimesis, fiction, and the control of the imaginary

1.

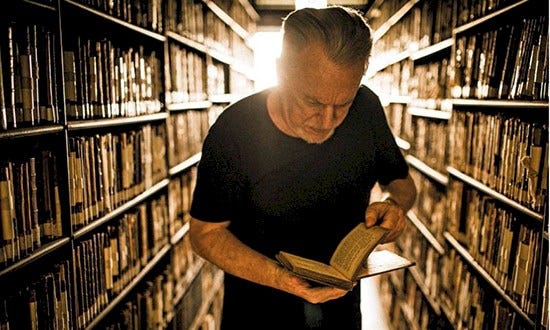

Many years ago I worked in a University library. I would re-shelve books in one particular section and after a while I began to notice that there was one book that I never had to re-shelve, because it was always there, always un-borrowed. A quick look in the catalogue system and I noticed that no-one had ever borrowed it.

Now there are two types of books that people don’t borrow. The first are usually not very good books. They are the majority of un-borrowed books. But the minority of un-borrowed books are usually good books, often very good books, but they are books that have not yet found a home, because what they have to say does not have an existing frame of reference in the intellectual culture. They are like figures without a ground.

Now there are two things I have learnt to be true in libraries. The first is that by far the most interesting books on library shelves are always the ones next to the book you have actually come in to borrow. And I think you can judge a person’s character by whether or not they look at those peripheral books, and whether or not they leave the library with more books than they first intended to borrow. The second thing I have learned to be true in libraries (and in bookshops as well) is that you should always, always judge a book by its cover; or at least by its title.

And this book that was sitting homeless on the library shelf, un-borrowed, had an intriguing title: The Dark Side of Reason: Fictionality and Power (1992). And an equally intriguing author name: Luiz Costa Lima. An author from Brazil, translated from Portuguese. So I borrowed the book and I read it – and I didn’t really understand much of it, but it was an increasingly intriguing state of bewilderment that it engendered. This was clearly the second type of un-borrowed book. So with the full resources of a library with international reach at my disposal, I tracked down two other books in English by the same author, with equally intriguing titles, Control of the Imaginary: Reason and Imagination in Modern Times (1988) and The Limits of Voice: Montaigne, Schlegel, Kafka (1996).

When I read the second book (Control of the Imaginary, although chronologically the first book published in English), I didn’t really understand a word of it. But when I re-read the first book (The Dark Side of Reason), I found a few shafts of light had emerged. Reading the third book (The Limits of Voice) was the same, but now re-reading the second book also made it start to come into sharper focus. I was acclimatising.

I clearly needed more books.

But the problem was: there weren’t any more books; or rather, there were many more books – nearly twenty in all – but none of them were translated into English. A fact I discovered after I had first tracked down (‘cyberstalking’ had not yet been coined) – using the World Wide Web and electronic mail – a bemused Luiz Costa Lima in Brazil. The other fact I learned was that this initial book – The Dark Side of Reason – was actually a selection of pieces from two other books, Sociedade e Discurso Ficcional (1986) and O Fingidor e o Censor (1988) – and that those two books constituted the latter parts of a trilogy of books that began with Control of the Imaginary (originally published in 1984 as O Controle do imaginário).

In lieu of learning Portuguese, I peppered Costa Lima with questions about his other books, and when that process exhausted itself, I managed to persuade a University here in Australia to bring Costa Lima out from Brazil for a symposium dedicated to his work. But really it was an excuse to meet him in person and to continue the interrogation about his works and ideas.

Around the same time I was invited to present a paper at a Latin American Studies conference here in Australia, which I declined because I was ignorant of Portuguese and had only read two and two-half books by Costa Lima. But what struck me as odd was the response I received: I was told by the convenor of this conference that that I should reconsider my refusal because I was, regardless, “Australia’s leading expert on Costa Lima.” Why? Because, as it turns out – and this was the actual response I received when I queried this appellation – nobody else in Australia has read the same two and two-half books by Costa Lima that I have read, and so, expertise being a relative value, I was currently it.

Perhaps I still am. (I also said at the time that I knew nothing about Latin America, and I was told not to worry because “Latin America” is a ‘shifting signifier’ – which certainly didn’t fill me with confidence).

2.

Now I raise this point of expertise or specialisation for a particular reason – almost as if the entirety of the previous section was narratively constructed to lead you, dear Reader, to this point – and that is that the nature of expertise or specialisation is not something which we usually consider. But doing so always reminds me of a comment by media ecologist, Marshall McLuhan, who defined expertise as a process of ‘organised ignorance’. Basically, the process of achieving a state of expertise – in whatever field or discipline you like – involves successfully arranging one’s entire thinking life, and organising one’s whole learning, around remaining ignorant of a very large part of the world that otherwise falls outside that field or discipline.

An expert, in other words, always walks out of a library with the very book they went in to borrow in the first place.

As it happens, Costa Lima himself avers the role of specialist or expert. For example, he opens the Limits of Voice with the following statement:

The author of the present work is not a specialist – not, at any rate, if a specialist is taken to be one who is solely concerned with a narrow field of endeavour. What sort of a specialist would deal with a French author of the Renaissance, Kant, and Kafka? The academic world recognizes the existence of philosophers, historians of philosophy and of literature, Romanists and Germanists; any author who crosses the boundaries between these fields will not seem serious enough to merit attention.

– and it is here that Costa Lima shows his hand, by going on to say –

When he disclaims the status of a specialist, the author defines himself negatively in terms of academic discourse; yet his text can be envisaged in no other terms. This inevitably brings to mind the old joke about the man with two professions: as a doctor, he was good lawyer; as a lawyer, he was good doctor. A philosopher who should happen to read what is said about Kant on the following pages may well evaluate the author as a good Romanist; a historian of French literature, upon reading the chapter on Montaigne, will perhaps feel that he might do better as a Germanist...

- and so on.

It is in this disavowal of expertise, however, where I think one of the keys to Costa Lima’s intellectual project may be located; or, rather, a key hole through which his work may be furtively observed.

And so from this vantage point, in what follows, I’m going to attempt three things, although not necessarily in the following schematic order. The first thing will be to outline Costa Lima’s basic ideas – the rehabilitation of mimesis, the control of the imaginary, and the emergence of fiction. The second thing will be to provide you with some background to Costa Lima himself, and the context out of which his ideas have emerged. The final thing I will do, against this background, will be to make some preliminary observations as to why I find these ideas interesting and important, and why you should, too. And if I can’t persuade you of this, then at least I hope to arouse your curiosity enough, so that if you ever see any of his books on a shelf, you will pick them up and read it.

3.

Cultural historians broadly agree that there was a crisis of sorts in the late medieval/early modern period in Europe, when the temporal structure of human consciousness shifted from being considered circular to being linear in its constitution. Out of this was eventually born the idea of progress, with this idea becoming very quickly conjoined with this underlying sense of linearity. It is commonplace nowadays to question this identification between historical progress and linearity, and to explore the idea of nonlinearity, while at the same time realising that we cannot return to some pre-linear, mythical past; that to question the idea of progress does not necessarily lead to a theory of decline, but requires instead other avenues of thought to be opened up.

Against this common intellectual understanding, Costa Lima’s work emerged from a series of reflections during the late 1970s-early 1980s, which resulted in the publication of his work Control of the Imaginary in 1984 (translated and published in English in 1988). He was initially concerned with exploring the relationship between the development of historical discourse (historiography) – which reached a high point in the 19th century – with what he identified as an associated veto on fiction.

In this early work, he traced the source of this question back to this crisis in the late medieval period, when individual subjectivity emerged as a necessary mediating strategy in dealing with the lack of flexibility in the dominant (circular) mental structure of the day. This lack of flexibility came from the clash between, on the one hand, a Christian cosmology that provided only a single, pre-determined interpretation to every experience and, on the other hand, a nonlinear temporal structure that could not adequately incorporate social change; while beneath both, the material cultural conditions of the period was generating experiences that could not be easily incorporated into either. It was within this context, for example, where Montaigne developed the essay form, in an attempt to come to grips with this new found heterogeneity of experience.

So as this dominant Christian cosmology was slowly abandoned, experience allowed for multiple meanings to be ascribed to each particular experience, and it was up to the individual to determine which of these competing interpretations was correct. A new guiding logic was thus required. And this logic was offered by the rise of reason. It is this idea that becomes central in modern philosophical discourse, for example, starting with Descartes, and being brought to completion in Kant’s Critiques.

So far this is all pretty standard fare in the History of Ideas. But it is here that Costa Lima focuses on a peculiar aspect of this formation of reason. He states: ‘Reason, then, during the era we are studying, constitutes itself in opposition to opinion and to beauty. Subjectivity admits of all three paths. But, if one chose to speak the truth, the correct option was foreordained.’ In other words, the pattern of formation which Costa Lima began to notice was that reason explicitly established itself through identifying other discourses as being “false” – or fictitious – while its own discourse was elevated – as a consequence of this process – to being considered, in turn, as therefore “true”.

This is sort of like establishing expertise through a process of organised ignorance, writ large. Or, another way of thinking about it: as creating the illusion of flight through clipping the wings of those around you.

In this way, the rise of reason is predicated upon – or so Costa Lima argues – the active suppression of fictionality.

For Costa Lima, the main instrument for this suppression of fiction during the Renaissance was the concept of imitatio (or imitation) by which the subject was rendered subordinate to an approved model. In ethics, this process was played out by the idea of decorum; while in poetics, it was the idea of verisimilitude that allowed reason to mediate between an individual and their experiences.

Now the counter-narrative that Costa Lima tries to introduce at this point turns on a closer inspection of this concept of imitatio, a Latin term which derives from a classical appropriation of ancient texts, in particular Aristotle’s Poetics, where it was, in Greek, first described by the term mimesis.

At the heart of Costa Lima’s work is the idea that mimesis, buried beneath this modern instrument of imitatio, is a mistranslation and a misconception of this prior Greek practice.

Originally, mimesis was directed, not at the reality of things, but solely at their potentiality. ‘Aristotelian mimesis,’ Costa Lima states,

presupposed a concept of physis (to simplify, let us say, of “nature”) that contained two aspects: natura naturata and natura naturans, respectively, the actual and the potential. Mimesis had relation only to the possible, the capable of being created – to energeia; its limits were those of conceivability alone. Among the thinkers of the Renaissance, in contrast, the position of the possible would come to be occupied by the category of the verisimilar, which, of course, depended on what is, the actual, which was then confused with the true.

Or, rather, with being the only truth worth considering.

This double meaning of physis (nature) in Greek is suggested also by Hans Blumenberg, in his genealogy of the idea of “imitation of nature”:

the concept of nature as a productive principle (natura naturans) and produced form (natura naturata). It is easy to see, however, that the overlapping component lies in the element of “imitation” [mimesis]. The task of picking up where nature leaves off is carried out, after all, by closely following nature's prescription, by taking what is inherently given and carrying it out. This interchangeability of art for nature extends so far that Aristotle can say that the builder of a house only does exactly what nature would do, if it were able, so to speak, to “grow” houses. Nature and “art” are structurally identical: The immanent characteristics of one sphere can be transposed into the other.

And yet, as Costa Lima points out, the misconception of mimesis as imitatio – as imitation, representation, copy – which has become the conventional usage of this term, is that it incorrectly focuses on the “imitation” of the natura naturata – the ‘produced form’ (Blumenberg), the ‘actual’ (Costa Lima) – and suppresses the dynamic, creative, aspect of mimesis as it pertains to natura naturans – the ‘productive principle’ (Blumeberg), the ‘potential’ (Costa Lima).

Mimesis, then, by simulating potentiality, is characterised rather by what Costa Lima calls the production of difference, but one which operates within an horizon of similarity. Or in Blumeberg’s terms, “art” and nature may be ‘structurally identical’, but substantively different.

For Costa Lima, this ‘horizon of similarity’ is characterised by being a socially acceptable standard which the individual initially attempts to identify with, or assimilate to; however, this is accomplished, or actualised, to a degree of lesser or greater difference. An exact copy is never achieved, even if aspired to.

One way of thinking about mimesis is by an analogy with magnets. Identical poles of two magnets when brought together repel each other. And it is this repulsion, this aspect of difference, within this otherwise shared horizon of identity, which creates a certain dynamism, or movement, that can only be overcome, if temporarily, by great force.

That force – what Costa Lima would describe as a control of the imaginary – is initially supplied by various instrumental concepts – operating under the precept of the imitatio – such as decorum, or verisimilitude, which are deployed by what he calls ‘reality-discourses’ – those authorised by reason – which attempt to impart truths about the world. Philosophy and History are two such discourses. But against this, there is another form of discourse – which Costa Lima calls ‘imaginary-discourses’ – which are authorised, not by a perception of the actual, but by the imagination, that is by a conception of the possible.

It is within this context that Costa Lima then reconsiders the emergence of fictional discourse – as an admixture of both reality- and imaginary- discourses. And such a discourse that exploits the potential for a greater difference that operates within mimesis, and the critical remove this allows. It is a critical remove which thus operates outside of the standard of true or false, and so is concerned more with questioning the socially established ‘truths’ – or standards of assimilation – than with replacing it or erecting fresh standards to be followed.

Fictional discourse is therefore not concerned with imposing truths onto the world, but rather with questioning truths that we are otherwise being subjected to or subordinated under at any given time and place. And it is this questioning force of fiction that is most disagreeable to the establishment of reason, and is why (advocates of) reason remain constantly vigilant against the proliferation of uncontrolled fiction; not because they are necessarily ‘false’ (which is a category that does not apply to fiction), but because they potentially raise uncomfortable questions about what we otherwise consider to be settled truth. In modern times, such questions are not censored or excluded – as in Plato’s Republic – in fact they are permitted, but only if they operate within prescribed limits. In other words, they are controlled. A contemporary form of such control, when faced with a work of literary fiction, is to be found in various academic literary theories and practices of literary criticism. (See, Notes on Reading, No. 1, where what I call ‘reading with intent’ is an example of this practice).

Rescuing fiction from this marginal position where it has been placed by reason – and institutionalised by universities, enforced by political regimes and various ideologies – is the initial motivation of Costa Lima’s intellectual project; for him, overcoming this requires a rehabilitation of mimesis, reconsidered as the production of difference (and not as imitation or representation). And it is this that has occupied him since the 1970s, tracing the contours and variations of this control across different cultural and historical contexts (that’s what his many, many books, untranslated into English, are concerned with).

4.

In stating all of this, I do not want to give the contradictory impression that Costa Lima’s work offers a model of interpretation that ought to be imitated or applied to texts in a prescribed way, such that those texts be used to illustrate the ‘truth’ of the control of the imaginary or of mimesis as the production of difference, and nothing more. That would be counterproductive (and hypocritical).

It is this questionable practice of interpretation that Costa Lima orients his work in direct opposition to – against what he calls industrial practices. As he states, in discussing Kafka, for example:

Although it is fitting that writers should state their intentions, it is no less advisable that they should avoid treating their object as the mere illustration of a hypothesis. The interpretation of a work runs the risk of turning into an “industrial” practice when the raw material must be laminated in order to fit the specifications required for the product. Thus, we have had a Freudian Kafka, a Heideggerian Kafka, a religious Kafka, a revolutionary Kafka, and so on. I do not mean that such appropriations are arbitrary, but that they overlook the tension that is characteristic of Kafka’s text and ignore its fictional specificity.

And it is to confront this ‘fictional specificity’ in any given text – over and against the backdrop of these various attempts at controlling it – that Costa Lima orients his work. This does not, however, simply result in a “Costa Liman Kafka,” for example. And I think this is one of the great strengths of his work; but also one of the more difficult aspects. Costa Lima begins by facing a work with the (informed) assumption that it is labouring under certain controls, but where this leads him is in no way predetermined by anything other than the specific text he is examining, in the first instance; but the processes of mimesis also requires, in the second instance, the active participation of the reader, dependent upon their own particular cultural context, in order to follow the fictional specificity of a given work, and to allow the critical perspective it offers to be deployed. And a reading or interpretation of a text is precisely the product of these two intersecting vectors – which do not persist long enough to be rendered into models to be imposed elsewhere.

Now what this means is that, being initially aware of the control of the imaginary, and of mimesis, in no way guarantees the outcome of any act of reading. Costa Lima certainly does not authorise any particular reading – and this is the difficult aspect of his work – because it places the onus upon the individual reader. It is not just a matter of simply applying a theory to a text and recording the pre-determined result. It is so much easier – and in terms of specialised academic discourse, producing bankable research and publication outcomes – so much more likely to be accepted in institutional circles, if we continued pursuing such ‘industrial practices,’ and keep trotting out, for example, Freudian Kafkas, and Heideggerian Kafkas, and religious Kafkas, and revolutionary Kafkas, and so on. But that doesn’t interest Costa Lima. It doesn’t interest me.

And it shouldn’t interest you.

5.

At this point, I’d like to step back and reframe the whole discussion in an attempt to contextualise some of these ideas, and hopefully make them more accessible.

As a Brazilian, Costa Lima is acutely aware of the position of being – geographically and culturally – a peripheral intellectual; that is, peripheral to the centres of global culture or intellectual metropoles. His later work often refers to this relationship between periphery and metropole.

And yet, what he never mentions – so this is my own interpretation, for what it’s worth – is that there appears to be an explicit connection between his understanding of mimesis and his self-reflective understanding of his own cultural and institutional position.

In short, he describes the situation of what he calls a ‘tropical intellectual’ as struggling against two prejudices. The first prejudice is that you are not taken seriously in your own intellectual community unless your work is authorised by the importation of some externally derived, metropolitan intellectual fashion (or model). For example, I had no problem doing a Phd in philosophy in Australia, on the work of Albert Camus, but would probably have struggled to find a University to accept my doing a Phd in Philosophy on the work of Jack McKinney, for example – unless, of course, it was in order to consider how McKinney’s work was related to either the Continental or Anglo-American philosophical traditions; because, of course, Europe or Britain/America is where ‘philosophy’ comes from, and not from some sheep farmer-soldier from rural Australia.

For Costa Lima, it was only as a populariser of German thinking – through his Portuguese translations of various works from the Constance School of Reception Theory in the 1970s that cemented his early academic reputation in his own country. Likewise, his Phd dissertation in the late 1960s (later published as his first book) could look at the work of fellow Brazilian, Clarice Lispector, for instance, but only through using the ideas of Sartre and Merleau-Ponty to help translate its Brazilian obscurity, so that other Brazilian intellectuals could learn to appreciate one of their own.

The second prejudice, coming from the opposite direction, is that if, as a tropical intellectual, you do happen to attempt an independent line of inquiry, one that issues from your peripheral cultural context, you run the risk of being misunderstood or ignored; or of your work being considered by your fellow tropical intellectuals as being, at best, parochial, or at worst, propagating nationalistic, ideas. This means that you will not be taken seriously at home and your thinking will be seen as being irrelevant abroad, because it is not mature enough to operate at the level of accepted metropolitan thought.

Add to this a very real frustration that regardless of what you write – especially if it is in Portuguese – the chances are you will not get the work translated and read overseas anyway. And if we remember that of the 20 or so books which Costa Lima has written, only two and two-half books are available in English – and only one in German – then you can begin to see why he has built up over the decades certain, understandable resentments, which require him to adopt what he calls an ‘ironical pose.’

And yet I think this negative self-perception is misplaced, because it is precisely this peripheral context that produced his ideas on mimesis and the control of the imaginary in the first place: I don’t think he would have arrived at these ideas had he himself come from a metropolitan context. To see what I mean, we need to reconsider the situation of the tropical intellectual – this tropical intellectual, in particular – from the perspective afforded by his rehabilitated mimesis. In this, what I am arguing is that Costa Lima has in his own work taken hold of both horns of this prejudicial dilemma, which he himself describes, and turned them into creative and productive projects.

On the one hand, he has resisted the idea that thinking emerges from some self-generating culturally internal myth, while on the other hand, he has resisted the idea that thinking must proceed through merely turning oneself into a copy of some external model of accepted (metropolitan) thought. In other words, thinking mimesis – as the (peripheral) production of difference within an (international) horizon of similarity – was itself the product of enacting such a mimesis from the perspective of his own cultural context. And it is the critical remove that this position as a peripheral intellectual provides, which makes this work so valuable and interesting. Because it means that we can, and should, engage with metropolitan ideas, but against our own peripheral cultural background, even if this is not explicitly stated in the works we produce. For example, The Limits of Voice examines 400 years of European cultural history, from Montaigne, through Kant and the German Romantics, up through to Kafka. But, I would suggest, it is not a book that could be written anywhere other than from the peripheries – and that is its value. And – I think – it is what makes this work also relevant to my own cultural context, Australia being itself a peripheral culture. It is relevant, however, only to the extent that it helps us raise questions that we should be asking, but it does not provide any ready-made answers that could be easily applied.

Or, as Billy Bragg says: ‘You can borrow ideas, but you can’t borrow situations.’

6.

In order to explore this line of inquiry further – and really, this is only a speculation - I want to ground it more in Costa Lima’s own personal context and background. There are two events, or moments, I want to offer for consideration.

The first is that Costa Lima, in the early 1960s worked closely with Paulo Freire – who later produced the idea of a pedagogy of the oppressed. Freire was, in fact, Costa Lima’s next door neighbour, during Costa Lima’s formative teenage years. When I asked Luiz about Freire he said that he was his ‘first real master and lifelong friend’ – and it is only within the context of Freire’s thinking that we can appreciate that ‘master’ and ‘friend’ are not exclusive terms. In his Letters to Cristina (1994), Freire lists Costa Lima, amongst others, as helping him set up the Cultural Extension Service (SEC) at the University of Recife, Brazil, in the early 1960s. He then singles Costa Lima out as being ‘fundamental’ to this process, especially with regards to his coordinating programs in literary theory and Brazilian literature, and his being the executive secretary of the “Cultural Journal of the University of Recife, Literary Studies”.

I don’t think it is too much of a stretch to consider how from this experience certain ideas took seed which would later develop in terms of a particular rethinking of mimesis. For a pedagogy of the oppressed implies a generally discernible control of the imaginary that must be overcome. After all, Freire’s basic idea is that the relationship between a teacher and a student is oppressive if the student is merely to become a carbon copy of the teacher – that is, if the relationship is based an oppressive imitation. And the revised, liberatory teacher-student relationship – as a more interactive and creative learning process – is certainly transposable to a reinterpretation of the author-reader relationship that is more in line with Costa Lima’s rehabilitated mimesis of production. It is this form of thinking, I would argue, against this background, that would later, in the 1970s, come into contact with the ideas of the German Reception Theorists – a set of practices that provide a creative and essential role for the reader, whom exists, in an otherwise peripheral position, vis a vis the author and the work. But it is a set of practices that Costa Lima approaches and reinterprets from a very Brazilian context.

And this leads me to the second moment. In 2007, Stanford University Press published an edited book called Crowds, examining this social phenomenon from various perspectives. It included a very brief piece by Costa Lima, in English. Now it is not the topic of crowds that I am initially interested in here, but rather the biographical meditation that Costa Lima wrote in response to this topic. In true Costa Lima fashion, it is at once understated and oblique, but forceful and direct at the same time. He describes how in 1960-61, after completing his undergraduate studies in Brazil he travelled to Franco’s Spain for further study. There he experienced firsthand what it is to lives under a right-wing regime, which he abhorred. On returning to Brazil in 1962, he started his work with Freire, in spreading literacy in Brazil. Then, in 1964, there was in Brazil a military coup d’état, and the beginning of a period of living (once more) under a dictatorship. Along with Freire, and many others, Costa Lima was arrested many times over the next several years, was involved in violent street clashes, had his passport revoked, lost his university position, and so on. Then in 1972 he was arrested again. He describes his firsthand experience of the advances that had been made in the use of electrical torture since 1964 – how the measures of repression had been professionalised – and how in 1972 his torturers were now expert, specialised – as if they had arranged their lives over the previous decade around remaining ignorant of a very large part of the world that otherwise falls outside the practice of torture and oppression – and how, then, after several days of experiencing their ‘professionalism’ first hand, blindfolded and kept in isolation, he was finally released, half-naked, into the street.

And this was only a few weeks before having to defend his doctoral thesis on the work of Clarice Lispector.

What is interesting about this otherwise horrific experience is that he contextualises it in terms of his response to the question of crowds. He begins this piece by discussing the right-wing idea of a people as a mass, which he experienced under Franco; he then discussed the left-wing idea of a people as a public, which he saw Freire’s Marxism as aspiring toward, before the coup d’état. He then describes how, as he states, the ‘mass = public equation became obligatory under the dictatorship, for one’s writings had to rely on code-words, and secret small group assemblies were the rule. My face-to-face contact with the multitudes was limited...’

After describing his experience with torture, Costa Lima offers this rather cryptic reinterpretation of his own earlier attitude:

That day came when, blindfolded as always, I was thrust in a car by my captors, who forced me to keep my head down. The vehicle advanced for several minutes, after which the blindfold was ripped off and I found myself tossed out into the street. Dressed in a T-shirt and underpants, I viewed the urban masses anew. And what I saw was neither a public nor a crowd: just a busy agglomeration of individuals.

Now this remains a cryptic conclusion if we don’t reinsert it back into his ideas developed later in that same decade; or rather, if we don’t consider these later ideas against this background. But it is here also that I should state something I purposely failed to make completely clear during the initial discussion of Costa Lima’s ideas, particularly in relation to the emergence of fiction.

Costa Lima distinguishes the term fiction from the term literature, and he does so intentionally, because fiction must be considered under two aspects. The first, and most common aspect, is that of literary fiction – this is defined by the coincidence of fiction and literature. Randolph Stow’s 1965 novel, The Merry-go-round in the Sea, which looks at the consequences of the Australian nation at war, is an example of a work literary fiction. But nations themselves are an example of what Costa Lima calls a necessary, conventional (or non-literary) fiction – it is fiction that operates outside of literature, and is located more in reality-discourses, which, as you will recall, establish themselves, through the control of the imaginary. Philosophy and historiography in the 19th century, for example, along with legal, theological, political, and scientific discourses, are examples of reality-discourses, that helped create the fiction of nations – a move that preceded, and provided justification for, for example, such nations in the 20th century to go to war with one another.

The idea of a nation is, of course, a very high-order fiction – but precisely one that Costa Lima describes fiction as being: that which is neither true nor false, that which lacks substantive reality in itself (because it only exists in the relationships between particular real entities, individuals, things, landscapes, and so on), but one that which – through a process of a control of the imaginary – takes on the aspect of being somehow ‘true’, and, somehow, fundamentally so. Anyone aware of Benedict Anderson’s notion of ‘imagined communities’ will understand what Costa Lima means by this. (As an aside, I should say that Anderson has only popularised an idea that finds its first (and better) expression in the work of Harold Innis, and later Marshall McLuhan – and it pains me greatly to have to play to the gallery by citing Anderson).

But just like the establishment of reason, in the 17th century, or fields of expertise, in the 21st century, necessary fictions, such as nations, assert themselves through a process of organised ignorance – that is, an ignorance of anything outside the nation, or by actively clipping their wings, in order to create the illusion of flight (by using torture, for example). Nations may be fictional – like their lower order counterparts: institutions such as the media, the university, the law, the economy, etc - but there are very real consequences of their asserting themselves as being otherwise.

At this, Costa Lima would argue: yes, nations may be necessary fictions, but it is only through literary fictions – such as Randolph Stow’s The Merry-go-round in the Sea, for example - that a critical perspective can be shone upon the fictional nature of nations and the real consequences of their assertions of reality: Randolph Stow’s novel, of course, being about an Australian soldier returning to his rural home after serving in the Second World War; significantly, it is a novel that was written and published in Australia in the 1960s, during our involvement in the Vietnam war.

It is at this point that we can hazard an interpretation of Costa Lima’s cryptic conclusion to his text about crowds, that, after having his blindfold removed, ‘what I saw was neither a public nor a crowd: just a busy agglomeration of individuals.’ In other words, beyond the necessary fiction of ‘public’ or ‘crowd,’ he saw only individual entities, we beings who endlessly suffer the consequences of the assertion of such necessary fictions, and the mechanisms of control that initiate and maintain these consequences. It is at this point that we can consider the possibility that Costa Lima’s excursions into the medieval crises of Christian cosmology, and beyond, his rethinking of mimesis, his investigation into the control of the imaginary, and the subsequent emergence of fiction – both literary and necessary, is not exactly a disinterested academic pursuit.

It is very much political.

For his first mature book, Control of the Imaginary, was conceived, written and published in Portuguese, in Brazil, during the second half of this military dictatorship that he, and many others, lived through (and, in many respects, live through still). In that context, the question of control takes on a certain political urgency, but also raises the problem of how to locate a space where this question can be considered within this otherwise controlled context. And this raises the importance of mimesis, and the role of fiction, but also the limits of such discursive inquiry. And this, I think, is what is really interesting about his work, and it is what allows it to resonates beyond his own context, and beyond the texts he reads. It is, at the same time, an invitation for us to consider what is beyond our own (institutional) blindfolds, beyond our own contexts – these conventional fictions – or the texts we read (or in the conventional ways in which we read them).

7.

Costa Lima slips into his book, Control of the Imaginary, the following statement:

The power of fictionality’s questioning of habitual norms does not presume the presence of any sort of revolutionary program “illustrated” by the text. How the reader is to cope with day-to-day existence on the basis of that questioning is a problem that does not concern the theory of the fictional in itself. To be sure, it can be linked to a political position of interference in the established order, but that will take place because the theoretician of fictionality is also, hopefully, a person of political convictions.

In this, if Costa Lima’s work was only about literary fiction, and ways of reading it, presented within an institutional discipline of comparative literature, then I would suggest that it is only of passing interest. But his work uses an examination of literary fiction to also bring into play a more radical questioning of the necessary fictions that surround us, and which shape our experience of the world, particularly within our institutional settings, the validity of which we tend to take for granted, feel entitled to, but which, after all, are not enough to sustain us.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

>In lieu of learning Portuguese, I peppered Costa Lima with questions about his other books, and when that process exhausted itself, I managed to persuade a University here in Australia to bring Costa Lima out from Brazil for a symposium dedicated to his work. But really it was an excuse to meet him in person and to continue the interrogation about his works and ideas.

I did this too! But with Sting. Which I guess symbolises all that is different, and the same, about the two of us.