Notes on Lucienne Rickard’s “Extinction Studies”

Toward an art form for the current moment

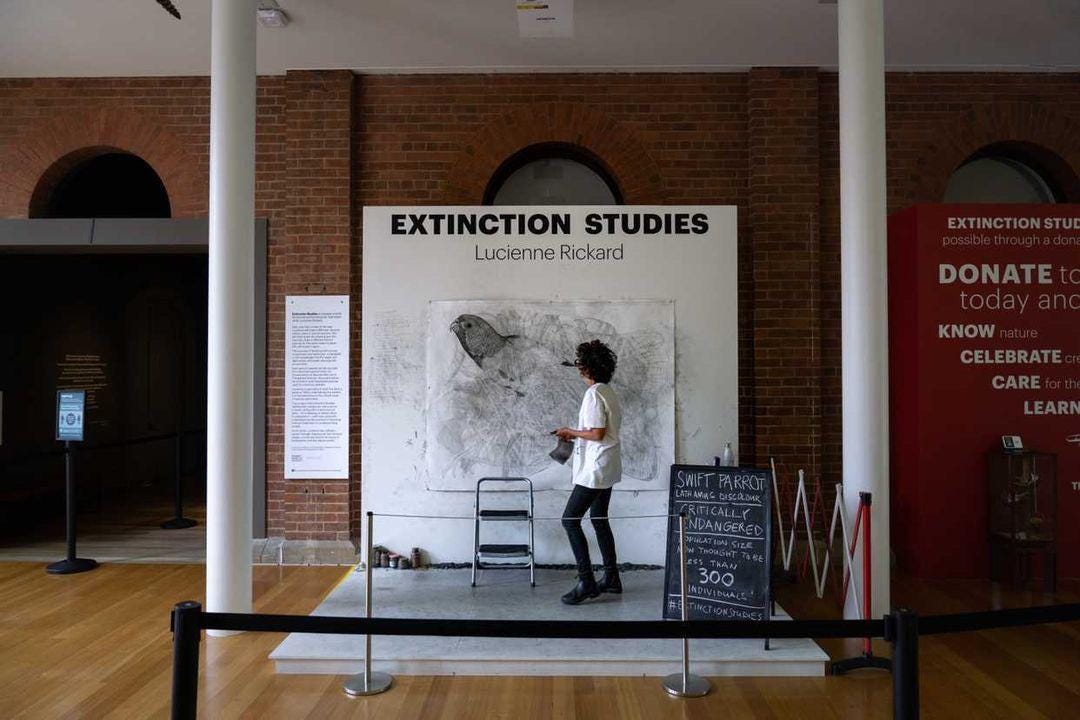

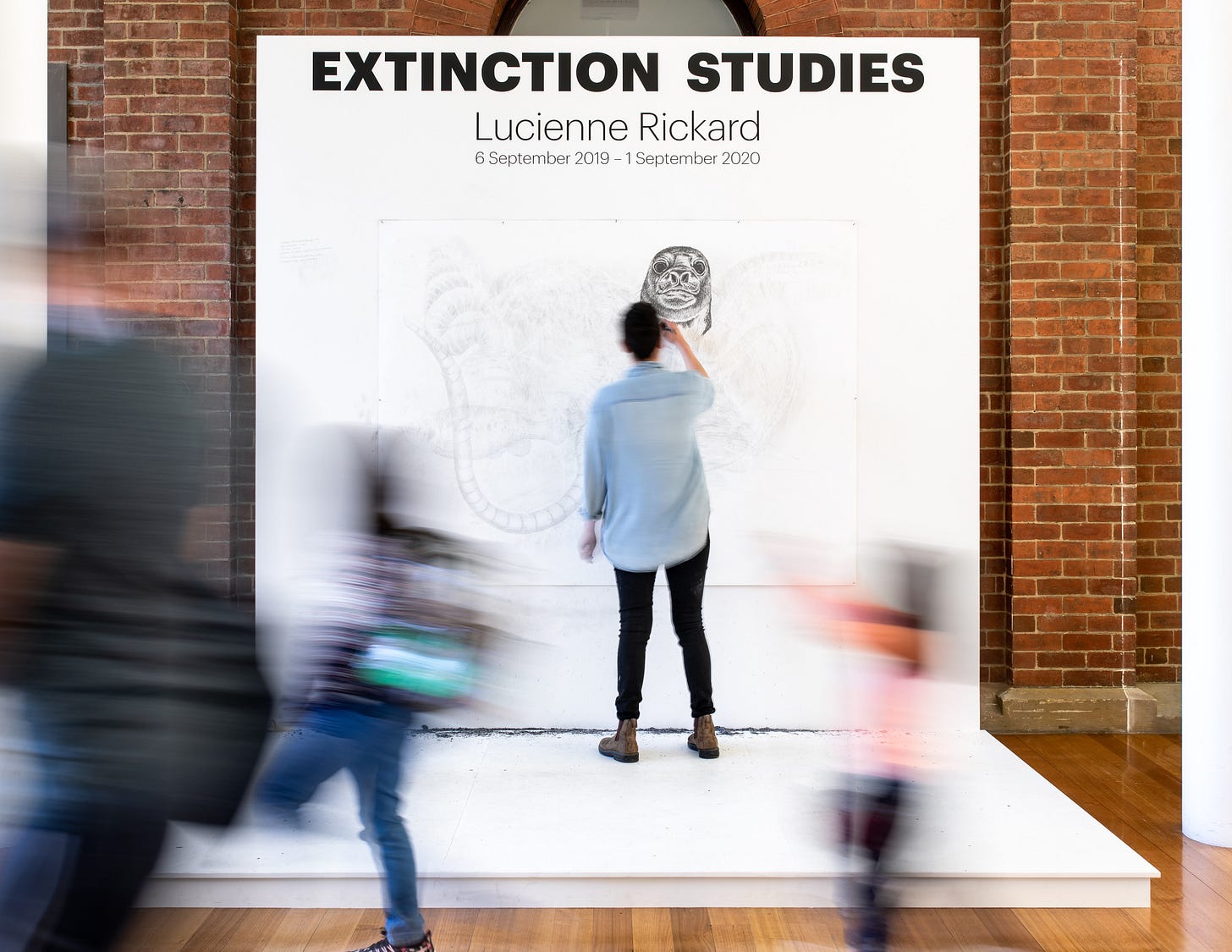

Extinction Studies sees Tasmanian artist Lucienne Rickard undergoing a daily reckoning: drawing, then eventually erasing, a recently extinct, or functionally extinct, species. Beginning each day during museum opening hours, Lucienne draws and then erases, over and over, on the same paper, different extinct species, eventually worn thin by the marks and indents of loss.

Each extinct species is sourced from the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, the authoritative list of extinct and threatened species used by scientists globally.

This project is presented at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. The first iteration ran from September 2019 through to January 2021. The second iteration is currently underway, having started in January 2022 and running through to December 2023.

Extinction Studies merges art and science, a ‘study’ being both a technical art term – for a drawing or sketch done in preparation – and more generally understood as the practice of devoting time and attention to understanding a topic, which, in this case, is the process of species extinction and concerns for the future of biodiversity in the natural world.

1.

In this work, the initial emphasis is on the act of making, rather than on the image made; on the process, and not the terminus. The point is to hold the terminus at bay and to retrieve the process – both in nature and in the act of making art itself.

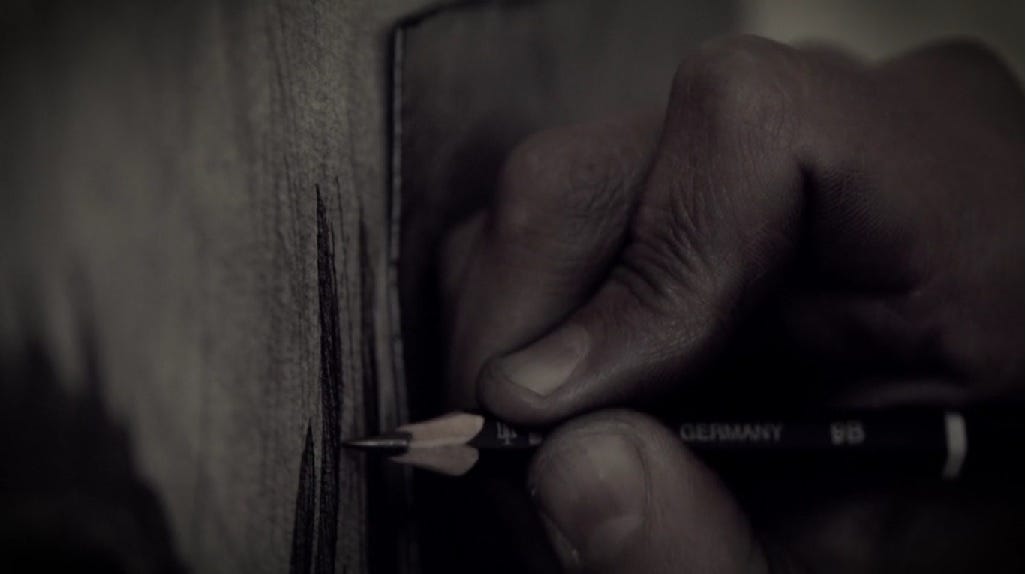

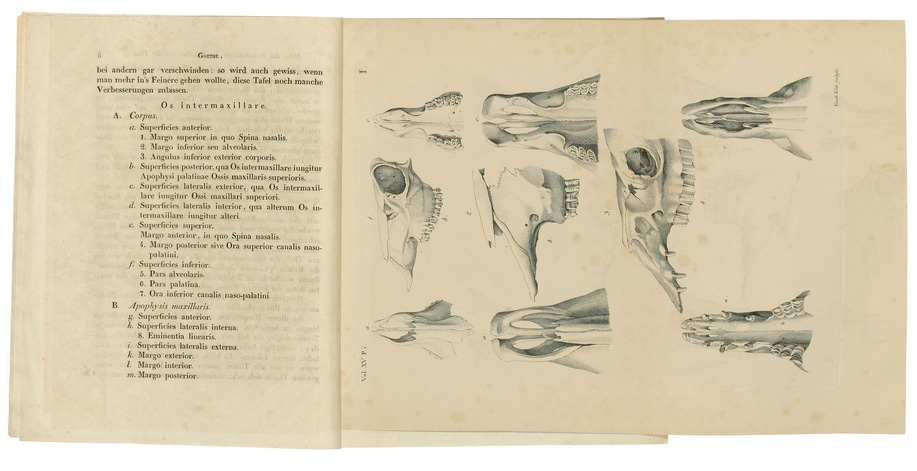

It is the hand that draws, the hand that holds the pencil, the pressure the hand exerts, that makes the marks upon the canvas. It is the hand that makes the images appear. Sight is subordinate to touch, the image to the material. And then only as an invitation to see what is usually left unseen.

The drawing proceeds by each mark overlapping with the next mark, and so on. To overlook this is to overlook the fundamental process of nature and our place within its web, with each figure connected to the next figure, endlessly overlapping, intertwining.

2.

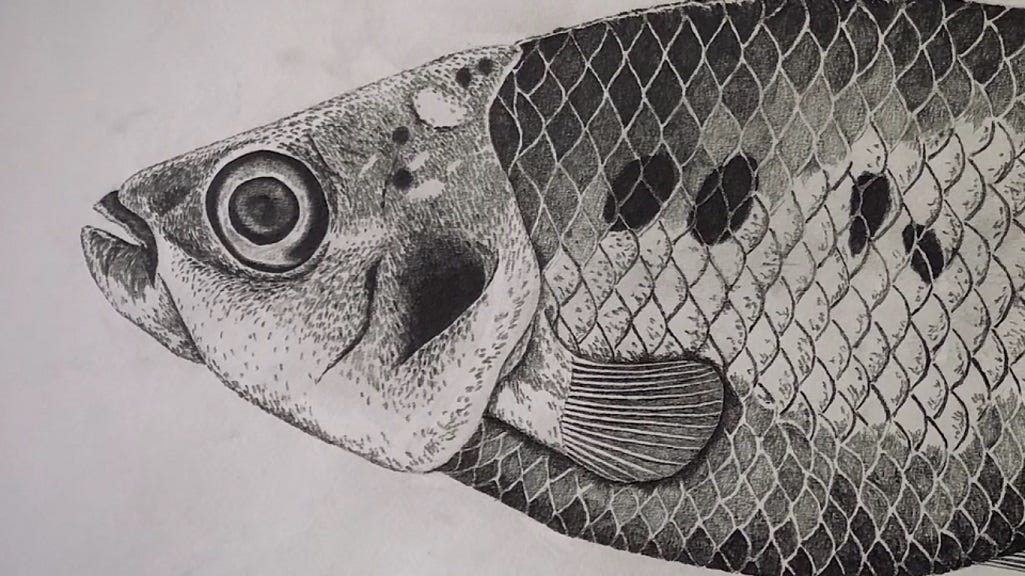

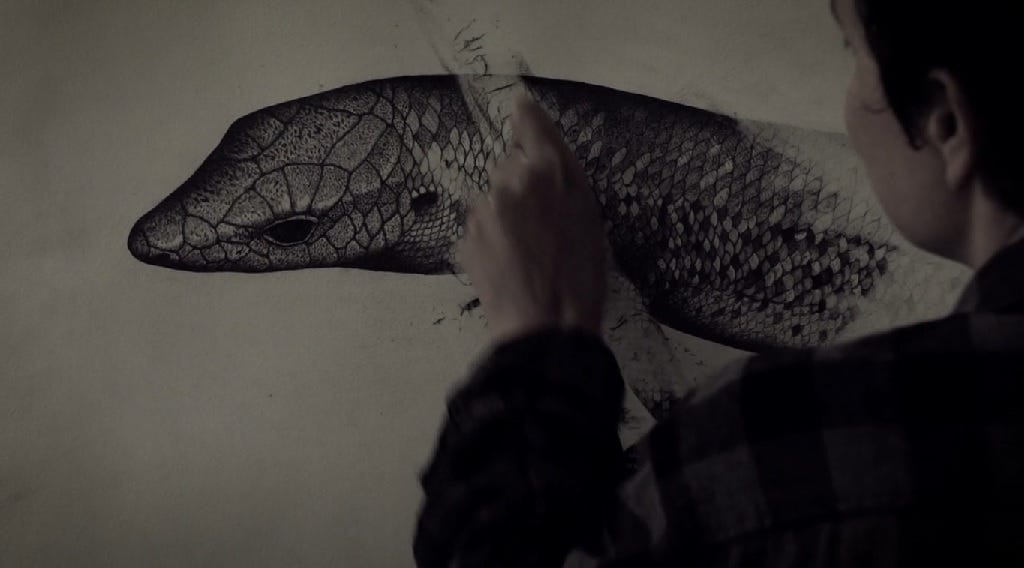

And as these drawings progress, as the detail emerges, there are elements of the hyper-real, of the photo-real, in each, in the sense that the emphasis is on making the image as accurate a depiction as possible. A bird, a plant, a lizard.

As much as possible, the human self is kept out of the making – no impression, no expression, no abstraction, no emotion, no concept – as though to disallow the human conceit to interfere into the natural process of making; to not interfere any further, that is.

And yet, this detachment is not without self, not without emotion – there is an anger, a grief at play – but these are redirected by the artist into an act of restraint, into the hand that draws, and into the overlapping marks that appear upon the canvas. Even as a motivating animus, these emotions are directed toward restraint, to undo certain processes, to refocus our attentions elsewhere – both in nature and in the act of making art itself.

In part, this shift in emphasis is from self to other, on the process that underpins both self and other, on the making and not the maker, on the natural conditions for making and not what is made.

3.

And yet, this shift in emphasis at the same time also breaches the dictates of the hyper- or the photo-real.

These drawings are not representations of reality, because what is being depicted is no longer part of reality, they are no more: the bird, the plant, the lizard, is already extinct or else functionally extinct.

They are drawn in black and white, rendered in grey-scale, and not in living colour. In part, this is done to put the image in stark relief, to make more visible. In part, this is done against a white background, separated from the natural background that otherwise supports these natural figures – for such support, their habitat, has been undermined, made uninhabitable, itself made blank.

In nature, the colours of these animals, these plants, are markings of survival – to disguise from predators, or to attract mating partners, in order to continue the species. But such invisibility has been their downfall, camouflaged from human concern they have been condemned into extinction, to such a degree that even their extinction is largely unnoticed, unconsidered.

Such colours have kept them out of sight. The lack of colour here, the lack of background, is to bring them into the light, for us to consider what is usually left unseen.

4.

The scale of each drawing also defies the dictates of verisimilitude. Each image is proportionately larger than the actual figure depicted – the animals, the plants, otherwise small in nature, inverse to their importance and worth – and this is because what is being depicted is not an individual animal or a particular plant as such, but a species entire.

And yet, at the same time, to the extent that each drawing may be of a particular plant, or a particular animal – this bird, this butterfly – it is only such because it is among the last of the species, if not the last, or else is a depiction of what is already past; a species reduced in number to its final individuals – that can be counted on human hands – or to nothing at all.

The scale works also to magnify, to put into perspective, to consider in detail what is otherwise overlooked, ignored, unseen. Or else, at the same time, by contrast, the scale is to place the human auditor of the work in a subordinate position, to reduce the human proportionately, to put ourselves into perspective, as part of, rather than separate from, a particular natural process otherwise overlooked, ignored, unseen.

5.

It is the selfsame human hand that makes each image that also makes each image also disappear. It is the hand that erases, the hand that holds the eraser, the pressure the hand exerts, that unmakes the marks upon the canvas, cuts across the web of overlapping marks, and removes them altogether.

The erasing is done in long strokes, not as controlled as the multiple, smaller strokes of the pencil that created the image in the first place. There is also a disproportionate amount of time between making each image and its erasing. The days, weeks, months, to create a single image, set against the brief moment it takes to destroy.

The millennia, the evolutionary process, that it took to create this species, or that species, and the human lifespan, the generations it has taken to undermine that process, to render extinct, and the disproportionate amount of time that stands each to each. This is the reckoning of the work.

Destruction is easy; creation requires effort.

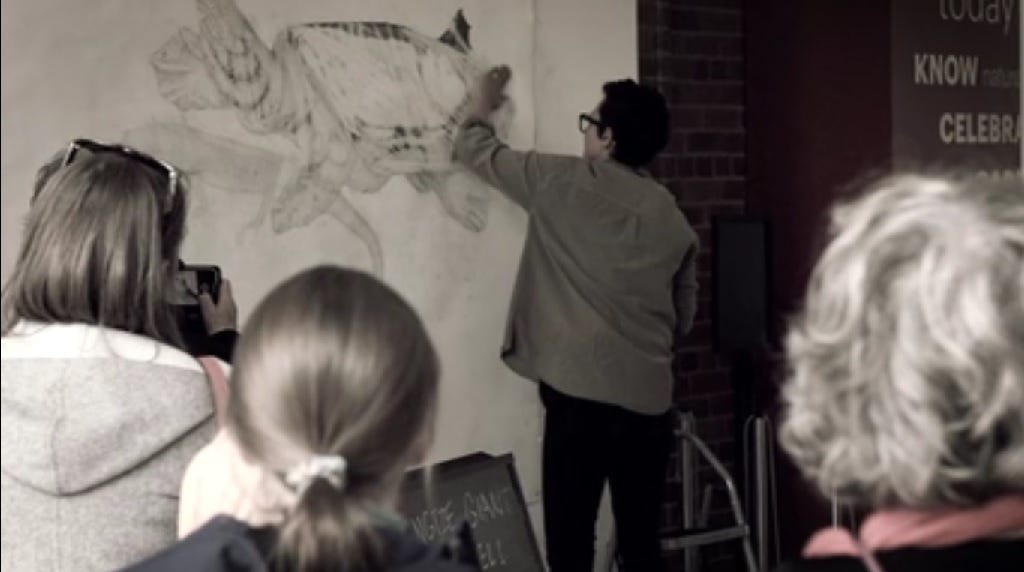

And yet here the hand that makes is the same hand that erases. The emphasis here is on the act of erasing as an intention, a choice. The artist implicates themselves in this process, and they implicate also the audience that stands back and watches each erasing, without intervention, as spectators to our own indecision, our own inertia.

We could choose otherwise.

6.

And yet, this is not a performance. The artist is simply doing in public what could otherwise be done in private, bringing the backstage of the studio to the front stage of the gallery, to allow us to see what is usually left unseen.

And what is usually left unseen are the by-products of the making of art, the waste. But here is the canvas, the eraser detritus, the pencil shavings, and pencil nubs.

And here the public are not positioned as an audience, separate and silent, but as auditors to interact with the artist, to disrupt the making of the work. Here the artist is embedded, responding to questions and comments. But the verbal interactions are not didactic, the artist is not transmitting any information that is not already publicly available, that should not already be widely known, but is simply showing how each of us are implicated in the ongoing processes of making and unmaking, the creation and destruction, of both nature and culture.

In this work, the act of erasing depicts the erasing of nature, the process of extinction, but it also depicts the erasing of art itself, the destruction of the work, emphasising that without the ground of nature, art itself cannot exist. As a result, no commodity is produced, there is nothing to sell: this project operates entirely outside the art market, while at the same time showing that the art market - indeed, the general market itself and all economics - is grounded in, and dependent upon, the natural world, and not the other way around.

Yet, there is here no room for displacing responsibility to others, no innocence. These erasings, these extinctions, are the result of human intention, human choices, constantly made and remade daily.

But the work calls on us to make different choices, to reconsider our intentions anew, and, in the process, to re-imagine art.

7.

Pre-modern art, in traditional societies, was based upon a relationship with nature in which the status of humans was precarious, and nature was both abundant and threatening to their survival. It was in responding to that overwhelming natural order that art first emerged, to give that order shape, a human form.

Modern art was then based upon a reconfiguration of that relationship in which humans were beginning to achieve a position in the world that was less precarious, in which nature was still considered abundant, but less threatening. Humans aspired to dominate their environment. And in that aspiration, in those ordered shapes and human forms, we retreated into the self, as if - but in reality not - separated from and set against that natural order.

The current moment is different again, and is based upon yet another reconfiguration of the relationship between human beings and nature. The status of humans is once more precarious, and nature is once more threatening to our survival, but at the same time nature is less abundant: it is itself under threat, and that threat is predicated upon the continued human aspirations of dominance over the environment; the result of which is, for humans, ultimately self-defeating.

It is this new configuration which requires an art that is responsive to the present moment, to that precariousness, that deficiency, and that self-imposed threat.

New ways of doing art, and thinking about art, are required, consistent with this new configuration. But such thinking remains stuck in that previous moment, which no longer exists, and which probably never really existed except in aspiration.

Works and practices and ways of thinking that do not account for this new reconfiguration, that operate as if the older configuration still prevails, are at best an anachronism, the avant-garde becoming a rear-guard movement, protecting a market, a reputation, a privileged status; that is, protecting the status quo. At worst, such works, such practices, lacking a necessarily new aesthetic, become anaesthetic, and fail at being art, settling instead for being an apologetics for various forms of cultural, economic, and political denial.

But among the works that do account for this new reconfiguration – this precariousness, this deficiency, this self-imposed natural threat – among the only works that today really matter, and may now be considered art – there is Extinction Studies.

Follow Lucienne’s progress on her Instagram. Many of the stills above are taken from this short film, where you can hear Lucienne discussing the project in her own words.

Sidebar: Toward a form of art criticism for the current moment

In legal terms, a sidebar is a discussion that occurs in a law court between the lawyers and the judge held out of earshot of the jury; in journalism, a sidebar is a short article placed alongside a main article, containing additional or explanatory material; but to my mind, a sidebar is also a small bar off from the main bar where a small group can sit over a quiet drink and converse, away from the din of the crowd. These sidebar pieces – for paying subscribers and special guests, my judges – are a combination of all three.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.