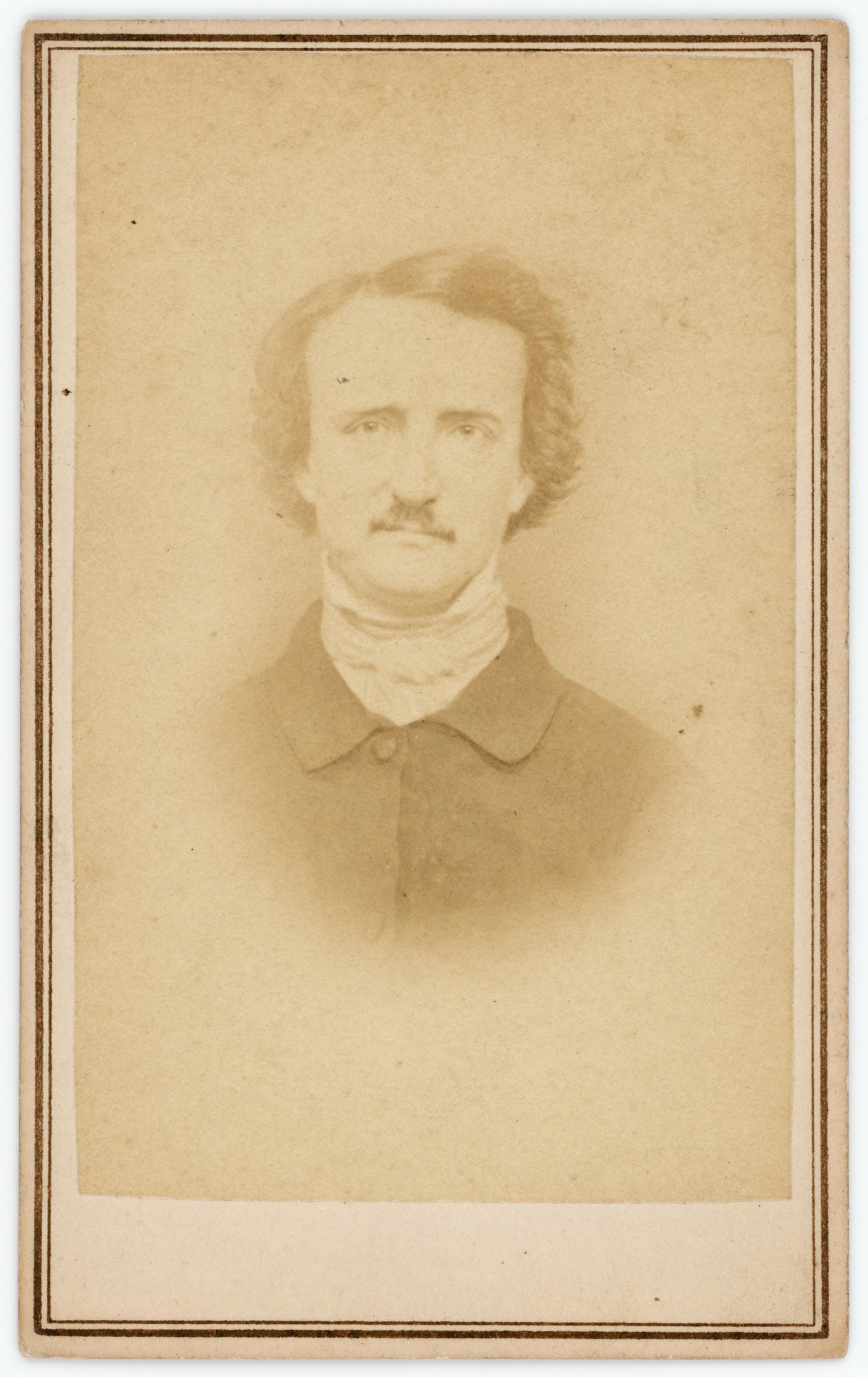

Last week I read a Substack article by Anne Trubek over at Notes from a Small Press newsletter (which I recommend), called: American Publishing is Rooted in Theft: Ripping off authors since 1790. It was a useful attempt at supplying some historical context – otherwise lacking – from the coverage of the Penguin Random House anti-trust case. In the comments I outlined how the same historical process that disadvantages authors in America is also at play in the Australian context. I was only able to speak to that because I am currently working on a biography of an Australian author, Frank Moorhouse, and I have had to examine the cultural and historical background of publishing from the 19th century onwards, to provide some necessary context to that project (Moorhouse led a famous court case here in Australia in the early 1970s that precipitated an overhaul of Australia’s outdated copyright law). As I also noted in my comment to Trubek’s post, in relation to the American scene, the figure of Edgar Allan Poe is also worth looking more closely at, as an example of an author trying to make a living in a world without an international copyright agreement (the Berne Convention only came into effect in 1887, or 38 years after Poe’s death). Previously, in a sidebar post for paid subscribers – on the distinction of reading with intent versus reading with consent – I used Poe’s short story, “The Purloined Letter”, as one of the examples to overturn intentional readings of the fiction, but in doing so I omitted a great deal of background to that story, pertaining to publishing conditions under which it was composed. Here I’m using Trubek’s recent post as an excuse to introduce that background. In doing so, I am leaning heavily on Kevin J. Hayes’ remarkable book, Poe and the printed word (2000); I also (in section 3 below) recycle the consensual reading of Poe’s story from the context of my previous sidebar post (to see the original context you really should subscribe...)

1.

The central thesis of Hayes’ study is to show how the changes in a burgeoning print culture in the early to mid-19th century impacted on the way literature was disseminated and (under-)valued. He also shows how, operating within this changing culture, and in largely thinking against it, these impacts also affected the way Poe approached the writing of his own fiction.

The low status of literary fiction in the 18th and 19th centuries may be measured against the two more socially acceptable forms of literature: poetry and history. The high esteem afforded figures such as Sir Walter Scott should not be seen as exceptions to this, because his novels were permissible solely because they were historical fiction; with the ‘fictional’ being subordinate to the ‘documentary’ elements of the work. The young Poe also participated in what was by then, as Hayes states, a longstanding ‘aristocratic Southern tradition of writing manuscript verse.’ It was a close-knit, gentlemanly manuscript culture, involving the writing of verse in long hand and either passing around the manuscript to read, or else for reading aloud at small social gatherings.

This manuscript verse culture was very much associated with an oral culture, in which the audience is directly known to the poet. But in the 1820s in the United States, daily and weekly newspapers, and monthly journals, began publishing verse. This shifted the oral manuscript culture into a non-oral print culture. Where the manuscript culture was largely a private affair, the culture of print was a public affair and, as such, one of anonymity (where reputation replaces personal acquaintance). And in an era where belles-lettres meets the printing press, this shift created, especially within the domain of poetry, a distinction between that which was worthy of publication and that which was better left for circulation amongst close associates. These domains, however, are not mutually exclusive, with many of the published verses in newspapers and journals, and in book form, usually emerging out of this manuscript culture. Certainly, Poe’s first published book of verse, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827), emerged from this manuscript print culture. Authored by an anonymous ‘Bostonian’, the preface to this work attests to the connection with the manuscript culture by the author asserting that this collection was ‘not intended for publication.’

Another consequence of this burgeoning print culture is the value placed upon the material work itself: with the shift from manuscript to print being at the time a shift from something unique and valued in itself, to something that was to become a mass-produced, disposable commodity, especially with regards to the proliferation of newspapers. By being associated with an oral culture, manuscript verse was not fixed; it could vary with each re-writing (or re-telling). Print culture, however, ensured that the work was fixed, and repeatable only in a uniform manner.

The conditions under which the manuscript culture operated included also autograph albums and letter writing. With autograph albums, individuals (usually women) owned bound manuscript volumes which were handed around and inscribed with a custom written verse. The handing over of an album for another to write in was therefore an act of both trust (on the part of the owner of the album) and honour (on the part of the poet). Hayes, citing the work of Donald Reiman, explains the significance of this:

In his fine study of modern manuscripts, Reiman distinguishes three basic types: private manuscripts intended for a single individual; confidential manuscripts often addressed to an individual but shared among members of such close-knit groups as family, friends, or co-workers; and public documents intended for dissemination to a wider readership. Poe well understood the relationship between his writing and his intended readership. Album verse, as Poe realized, were confidential manuscripts written for the album owner and a handful of her close associates with whom she might share the album. Furthermore, confidential manuscript verse could be used as social capital.

Such forms of trust and honour, which increased social capital, also extended to letter writing, which was an even more personal form of writing operating within an already private manuscript culture. Letter writing also had its own rules of etiquette; for example, letters of introduction were normally written by a third person who was already a mutual acquaintance. Poe often broke this etiquette, however, by introducing himself directly via letters to potential connections in the publishing world. But what is interesting about the way Poe approached this breach of propriety is the way he included within his letters a piece of verse. As Hayes concludes: ‘In this letter, manuscript verse again functions as social capital. As album verses heighten the relationship between poet and album owner, this manuscript poem softens the impropriety of Poe’s self-introduction and creates an intimacy between poet and publisher.’

That Poe was keenly aware of the difference between manuscript and print cultures is also evidenced by the fact that he used cursive writing for both his private correspondence and manuscripts, but used Roman print characters when communicating in letters with publishers. This awareness also shaped the way he eventually came to approach the composition of literary fiction. For although of lower status than historical and other ‘non-fiction’ publications, there was during this period a growing market for serial-fiction, with instalments first published in newspapers or monthly journals, and then collected together and printed in book-form. In an initial effort to conform to the market and to the changing demands of print culture, Poe tried his hand at writing such a serial novel. The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket imitated the popular genre of ‘imaginary voyages’ (such as Robinson Crusoe), which operated under similar strictures in relation to travel literature as historical novels did in relation to documentary histories. This work, however, was an unmitigated disaster, commercially and artistically.

Commercially, because the 1837 economic panic and subsequent depression led to a reduction in the number of locally produced novels being published in the United States; the publication of Poe’s novel was therefore initially suspended, and when it came out the following year it reviewed badly and sold poorly. Artistically, because novel writing was governed by many social strictures, moral and educative; but also, because of the length of the novel form, Poe felt that the necessary coherence of an artistic work could not be sustained.

By this stage, Poe had already decided to give up trying to be a professional writer. But by 1840, the lack of money drove him once more to attempt another novel. This work (The Journal of Julius Rodman) was abandoned after the first six instalments, and out of this abandonment a fresh decisiveness emerged in Poe’s artistic endeavours. This decisiveness emerged in two ways, both of which are associated with promoting a growing sense of fictionality in his work. The first is his renewed focus on the short story form, as opposed to the serial novel. As Hayes explains:

In his short stories, Poe had repudiated the idea [that literature must ‘delight and instruct’] in favor of a forward-thinking attitude toward literature as solely an aesthetic object, something which delights yet need not instruct. Being a relatively new literary genre, the short story had yet to receive much critical scrutiny, so it escaped the standards by which book-length narratives were judged. Books, because of their length as well as distinct works, were bound by stricter rules than short stories.... Poe was a meticulous literary craftsman, and he believed that the long story could never achieve the tale’s level of craftsmanship. . . . Short stories allowed authors tight control of plot, action, and character, providing the opportunity to tell a highly compact tale, layering multiple levels of meaning one atop another.

This tightened focus enabled Poe to chart an alternate course between externally imposed social norms and the internally weak structures of longer forms of narrative. It provided a space within which he could focus on fiction qua fiction.

The second way Poe’s new artistic decisiveness emerged was in his awareness of the hybrid form of writing out of which fiction was created. In this, Poe’s sense of fiction emerged from the coming together of manuscript and print cultures, and with his use of the conventions of manuscript culture within his writing to undermine and question the dominance of print culture. Four examples (drawn from Hayes’ study) from Poe’s writing may attest to this:

a) In 1844, Poe published a story in a newspaper that has since become known as “The Balloon Hoax.” At the time, however, it was printed uniformly, alongside ‘real’ news stories in the paper, complete with a headline, a by-line and woodcut illustration. By mimicking the format of the print media, while deploying the tall-tale of oral culture, Poe undermined the print culture’s pretension of authority and ‘objectivity.’

b) In 1835, Poe wrote an article in which he drew upon the conditions of the manuscript culture. Entitled “Autography,” this series of small sections contained, first, a type-set print of the text of a letter (which he made up himself), but he then attributed it to an existing author; second, this was followed by a wood-cut facsimile of the actual author’s signature; third, Poe then analysed the ‘chirography’ of the author (which allowed him to be more critical than in his usual literary criticism); and so on.

c) Another article, combining manuscript and print cultures, was Poe’s series on “Marginalia.” Here Poe printed the margin notes inscribed in various books and printed them together in a magazine. Such marginalia acts to personalize the ownership of particular print books, bringing it in line with the conditions of manuscript culture. But Poe complicates matters by printing these margin notes without reference to the books they inhabited. In other words, he removed the marginalia from their print context. This is complicated further by the fact that Poe fabricated the notes in the first place. The personal library which he informed the reader he inhabited, the books he claimed to have been perusing and in which he found the marginalia, as well as the marginalia itself – were all acts of fiction.

d) For Poe never had a library, and he could not even afford to use the circulating libraries currently appearing in American cities. He received books from reviews, and from friends, but sold both to second hand shops almost immediately. But his imagination was filled with libraries, and libraries in turn fuelled his imagination.

Print culture afforded an author a greater distance and anonymity from his audience than with the manuscript culture, which relied upon closeness and personal acquaintance. And Poe exploited this difference, to undermine the supposed ‘objectivity’ of print culture, by creating for himself – as a literary critic and article writer – a fictional persona. For the main, this persona enabled Poe to project the image of what he was otherwise not: a well-to-do gentleman with a vast personal library. It was within this imaginary library that Poe found his reported ‘marginalia’, gathered his ‘autographic’ materials, and reported on worthy news stories (like a trans-Atlantic balloon crossing). It was also out of this imaginary space that he wrote his literary fiction.

It is interesting to note also how the image of the library and of books operates within Poe’s fiction as cues for the imaginary, for entering into fictional space. Hayes identifies this recurring ‘library’ motif in much of Poe’s fiction. For example, regarding the story “Bernice,” Hayes states: ‘The narrator personally identifies with the library. . . . Indeed, the imaginative world the library represents has affected him so profoundly that he loses the ability to discriminate between the imaginary and the real’; regarding “The Fall of the House of the Usher,” Hayes notes that most of the books in Usher’s library which obsess him so are either imaginary journeys or geographies: ‘Placing such voyages within Usher’s library, Poe reinforced the significance of the imaginary world over the real’; while regarding “The Sphinx,” Hayes offers a description of the narrator which may well describe also Poe himself: ‘The book, in other words, leads to a new way of perceiving the world. Succumbing to the library’s influence, the narrator transforms elements of actual topography and entomology into a landscape of the mind.’

2.

It is against this material-cultural background that we are better able to see the fictionality of Poe’s story “The Purloined Letter.” It was first published in 1844 in The Gift, an annual gift-book that mimicks the autograph album of the manuscript culture. During this period, as we have seen, Poe was concerned with the interaction between this manuscript culture and a burgeoning print culture. One of the aspects of this burgeoning print culture that Poe was most concerned with was the lack of international copyright law. In the late 1830s, the pamphlet novel was the cheap paperback of the day. The lack of international copyright meant that British and European novels (in translation) could be effectively stolen by American publishers and reproduced on poor quality paper, with small font, and sold cheaply. More cheaply, in fact, that the locally produced novels, which had to pay author’s royalties and rights. This led to a glut in the market for foreign novels in the United States. But this trend also worked the other way, with American novels being stolen by overseas publishers and reproduced in Britain and Europe (in translation), with the authors receiving no payment.

Poe – along with every other American author – was caught in the middle of this. ‘Without an international copyright law,’ he wrote in a letter in 1842, ‘American authors may as well cut their throats.’

During this period, in Britain, many of Poe’s contemporaries and friends had work pirated and reprinted in bowdlerized versions. In 1841, Poe’s only novel was published in Britain as Arthur Gordon Pym: Or, Shipwreck, Mutiny, and Famine. This was followed by other stories, such as “The Gold Bug” and “The Facts of M. Valdemar’s Cave,” which was passed off as a true account of mesmerism. Poe’s stories were also translated in French in the 1840s and it is through these pirated copies that Charles Baudelaire first became acquainted with his work. Baudelaire later translated many of Poe’s tales and essays, and produced biographical sketches, that spread Poe’s fame in France. It is through Baudelaire that Stéphane Mallarmé first became interested in Poe, resulting in him learning English solely to translate Poe’s poetry into French. What is interesting to note about all this international attention to Poe’s work is that, being based upon pirated translations, it was instigated at no material reward to Poe himself. And, of course, this continued long after Poe died (in 1849 from alcoholism and poverty), when Baudelaire first published Histoires Extraordinaires in 1856 (which included a translation of both “The Murders in Rue Morgue” and “The Purloined Letter”).

Poe’s reaction against this culture of publishing piracy also made its way into his fiction. William Harrison Ainsworth was a British author whose pirated novels were successful in the United States; Poe named Ainsworth as one of the men in “The Balloon Hoax” who crossed the Atlantic, from England to America. This story – written the same year as “The Purloined Letter” (1844) – was therefore, in part, a reaction to this lack of international copyright; or, as Hayes calls it, ‘a comment on the swiftness with which mediocre British literature made its way to America.’ Charles-Paul de Kock was one of the French authors whose popular pirated novels also annoyed Poe; so much so, that Poe gave the name ‘De Kock’ to one of the lunatics in his story, “The System of Dr. Tarr and Professor Fether” in 1845 (a year after writing “The Purloined Letter”).

Although it seems odd that Poe should blame the authors for their work being pirated, this background possibly highlights two initial aspects of “The Purloined Letter.” First, it suggests that Poe purposely chose a French setting and protagonist for this story (and the previous Dupin tales) to appeal to his fellow countrymen’s appetite for foreign literature. And second, it points to the significance of the conditions of a manuscript culture, which has been compromised by the print culture, by describing the interception (by an individual act of piracy) of a letter from its intended audience. And so, I would argue, it is where this manuscript culture and print culture meet that provides the necessary fault lines for the emergence of Poe’s fiction.

The first two stories of the Dupin trilogy – “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “The Mystery of Marie Roget” – are focused on private individuals being murdered in the public arena. Their deaths are reported in the newspapers, and it is through an analysis of the information detailed within this print culture that Dupin first becomes acquainted with the crimes. Significantly, it is through the exercise of his imagination, and through focusing on what the newspapers ignore, that Dupin is able to solve each crime. What’s more, it is through undermining the authority of such print culture, and by resorting to fictional techniques, that Dupin is able to solve each crime. In “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” for example, Dupin places a fake advertisement in a local newspaper – in much the same manner as Poe presented his “Balloon Hoax” – in order to lure the owner of the Ourang-Outang out into the open. While in “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” Poe takes an actual murder (of Mary Rogers) and transposes it into a fictional key. It is then through these seemingly innocuous differences (for example, setting the murder in France rather than the United States, and so on) that Poe’s narrator is able to create the necessary critical remove to enable him to solve, not only the fictional crime – or Marie Roget – but also the actual crime – of Mary Rogers; as Poe inserts in a footnote to the later republication of the story:

Herein, under pretence of relating the fate of a Parisian grisette, the author has followed, in minute detail, the essential, while merely paralleling the inessential, facts of the real murder of Mary Rogers. Thus all argument founded upon the fiction is applicable to the truth: and the investigation of the truth was the object. . . . It may be important to record, nevertheless, that the confessions of two persons (one of them the Madame Deluc of the narrative), made, at different periods, long subsequent to the publication, confirmed, in full, not only the general conclusion, but absolutely all the chief hypothetical details by which the conclusion was attained.

“The Purloined Letter” differs from these earlier stories, however, by the fact that the crime investigated is not a murder (it is a theft), the victim is not a private citizen (but is the Queen), and the media deployed is not a print-newspaper (but is a manuscript-letter). “The Purloined Letter” is therefore focused more on the conditions of an aristocratic manuscript culture, with the emphasis therefore placed on a breach of trust (the Minister intercepts a letter addressed to the Queen alone), and the possession of what is a unique an inherently valuable material object: the letter. The value of the letter is thereby measured against the background of an oral culture, which conditions the manuscript culture; it is at the same time distinguished from the print culture, by not being fixed or repeatable only in a uniform manner.

What is common to this trilogy of stories, however, is the method by which Poe (and Dupin) arrive at these dénouements: the critical use of the imagination. ‘But it is by these deviations from the plane of the ordinary that reason feels its way, if at all, in search of the true.’ In this, Poe’s narrator confirms a distinction initiated by Coleridge, between fancy and the imagination, and finds in this distinction, the necessary route by which to deviate ‘from the plane of the ordinary’: the analytic use the fictional. ‘Between ingenuity and the analytic ability there exists a difference far greater, indeed, than that between the fancy and the imagination, but of a character very strictly analogous. It will be found, in fact, that the ingenious are always fanciful, and the truly imaginative never otherwise than analytic.’

This shared context is reinforced by the persistent link that unites Dupin and his narrator: libraries and books. They first meet, in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” in an ‘obscure library’, while both men are in search of the same, rare volume. This is repeated in the opening section of “The Purloined Letter” which finds Dupin and the narrator sitting in Dupin’s ‘book-closet’, discussing their previous cases and their initial meeting in another library. In this connection, it should be recalled that the image of a library is a recurring motif in Poe’s work, reinforcing, as Hayes has said, ‘the significance of the imaginary world over the real’; this leads to ‘a new way of perceiving the world,’ as Hayes has concluded: ‘Succumbing to the library’s influence, the narrator transforms elements of actual topography and entomology into a landscape of the mind.’ Against this imaginary background, then, fictionality emerges.

3.

This leads us to a reading of “The Purloined Letter” that goes against much that has otherwise been said about this story by philosophers and critics and academics over the past several decades, many of these turning on the claim that the stolen letter supposedly has no content – is an empty ‘signifier’ – and that this absence apparently structures the interactions with all the characters in the story, underpinning the narrative itself, which thereby exists beyond all materiality. In other words, the story illustrates a theory, while the theory obliterates the story.

And yet, in the context of the story itself, the contents of the stolen letter are known, and to an ever increasing circle of people. And the purpose of the actions within the story is precisely to ensure that this circle doesn’t increase any further. In the story, when the Prefect first tells Dupin, and the narrator, of the stolen letter he describes it as ‘a document of the last importance,’ that it is ‘from the nature of the document’ that may give ‘its holder a certain power in a certain quarter where such power is immensely valuable’; that is, it ‘would bring in question the honour of a personage of most exalted a station.’ Already, a reader may feel safe in assuming that it is not the letter’s empty form alone that has endowed it with this significance; but rather, its contents.

The Prefect goes on to describe the scene of its theft, and in doing so, the Queen’s actions are stated clearly: ‘During its perusal she was suddenly interrupted.’ So, we may assume, the Queen had enough knowledge of the letter’s contents, after her ‘perusal’, to know that she did now want her husband, the King, to know of it. ‘The address, however, was uppermost, and, it contents thus unexposed, the letter escaped notice.’ But here the Minister ‘recognizes the handwriting of the address, observes the confusion of the [Queen], and fathoms her secret.’ The ‘secret’, of course, at this stage is not necessarily the exact contents of the letter. What the Minister notices, however, is that whatever this content may be, the Queen does not want the King to know it. Even so, at this early stage of reading the story, the impetus for this first scene is clearly not, as some would have it, because the letter is an empty signifier, as it is the Queen’s knowledge of the contents of the letter that makes her hide it from the King, and subsequently makes the Minister curious enough to steal it.

Later, when Dupin asks the Prefect for an ‘accurate description of the letter,’ the Prefect produces ‘a memorandum-book’ and ‘proceeds to read aloud a minute account of the internal, and especially of the external appearance of the missing document’ (italics added). Would it be safe to presume that what is meant here by the ‘internal… appearance’ of the letter is the text, and subsequently the content, of the letter that is being referred to? Any such ‘minute account’ would surely include this information. But let us not rely on this point alone.

Later, when Dupin retrieves the letter from the Minister and hands it over to the Prefect, the Prefect is said to have ‘grasped it in a perfect agony of joy, opened it with a trembling hand, cast a rapid glance at its contents, and then, scrambling to the door, rushed at length unceremoniously from the room and from the house’ (emphasis added). So, yes, it is therefore safe to assume that there is explicit evidence in the text of the story to claim that not only did the Queen know of the contents of letter, but that the Prefect did also; and from this one could then assume that the contents were at some time revealed to the Minister, and even to Dupin (to facilitate its retrieval).

Whatever one assumes, one would certainly not be safe in presuming – as decades of literary theory and academics’ intentional reading practice has had us believe – that just because we as readers of the story lack explicit knowledge of the content of letter, that the characters within the story must also share this ignorance.

A skeptical reader may raise doubts on our assumption that the contents are known to the characters in context of the story. But this leads us to the essential point of the story: that the contents of the letter are only secondary to the power or influence given to the person who possesses the letter. This is clearly stated at the beginning of the Prefect’s story, when he says that it is known that the item is still in the Minister’s possession:

“How is this known?” asked Dupin.

“It is clearly inferred,” replied the Prefect, “from the nature of the document, and from the non-appearance of certain results which would at once arise from it passing out of the robber’s possession; - that is to say, from his employing it as he must design in the end to employ it.”

“Be a little more explicit,” I said.

“Well, I may venture so far as to say that the paper gives its holder a certain power in a certain quarter where such power is immensely valuable.”

This point is reinforced on the following page:

“It is clear,” said I, “as you observe, that the letter is still in possession of the minister; since it is this possession, and not any employment of the letter, which bestows the power. With the employment the power departs.”

In other words, it is ‘the paper’ – the material possession of which – plus the ‘contents’ of the letter, which gives the Minister his power over the Queen. By retrieving the physical letter from the Minister, relieving him of its possession, Dupin has relieved him also of his power over the Queen. Why? The Minister may repeat the contents, in the form of a verbal rumour, in order to disparage the Queen, but without the physical proof to corroborate those aspersions – which come from both the content and material existence of the letter, in support of that content – that rumour lacks the power to inflict permanent reputational damage. In other words, according to “The Purloined Letter”, the stolen letter does indeed have content, and it is this content, and its physical character – in the form of the very paper it is written on – that structures the interactions with all the characters in the story, underpinning the narrative itself, which is thereby grounded in a sense of materiality.

4.

We have examined, in part, Edgar Allan Poe’s place within a shift in culture, from manuscript to print; but this is only a slice of a much longer historical process, from oral to literacy, within literacy from auditory to silent reading, and again from manuscript to print, and from print to digital. That longer story would require us to take a foray into the field of media ecology, of Marshall McLuhan and co. But that will be a story for another time.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.