On literacy, the value of reading, and the free circulation of written materials

A brief talk given at the State Library New South Wales, August 2025

A couple of months ago I had to give a brief talk at the State Library New South Wales because my unaward winning book, Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths, was shortlisted for the 2025 National Biography Award. We were supposed to read an excerpt from our books, but instead I said the following…

I don’t have an excerpt from the book to share with you. Instead, I want to tell you a story about Frank Moorhouse, a story that speaks also about where we are today, here in the State Library of New South Wales.

Frank was born in Nowra on the South Coast in 1938. At age 11 he had written his first short story; and he continued writing from that point on – producing throughout his adolescence many short stories and essays, as well as the draft of a novella – before having his first short story published in Southerly journal, when he was 19 years old.

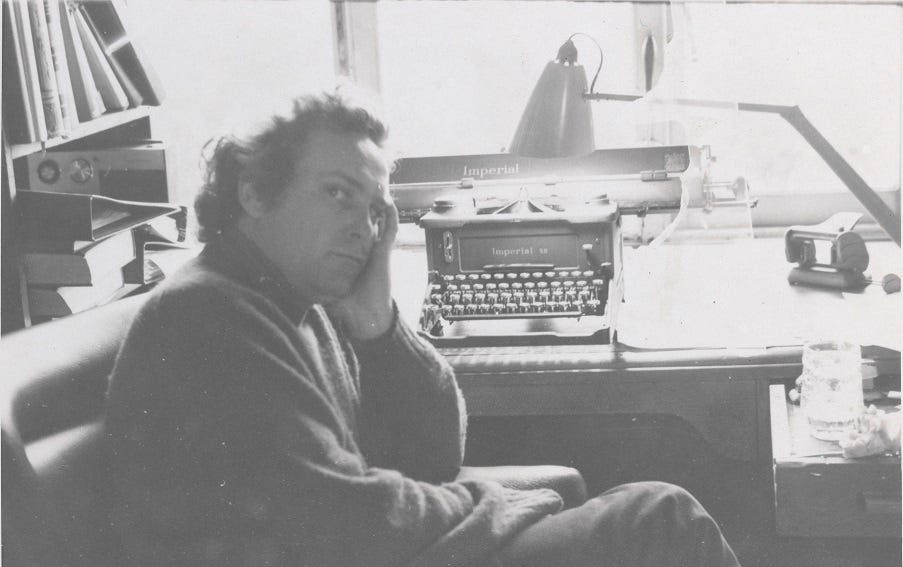

But what interests me is that in the background to this process of becoming a writer there is an equally important process of becoming a reader. And during this same period, Frank read what ever he could get his hands on, which, in Nowra in the 1950s, was not much – but it was enough. Later Frank would categories these sources of childhood reading as coming from what he found in the house – his parents books, newspapers, and magazines – books he was encouraged to read at school (for example, one teacher introduced him to John Buchan) – books given to him as gifts (his Aunt Sylvie, for example, from New Zealand, gifted Frank a copy of Katherine Mansfield’s collected short stories, as well as an Imperial Typewriter, which he used to write everything for the next twenty years) – but also books he found or came across accidentally (including a copy of Ernest Hemingway’s First Forty Nine Stories in a second hand shop on Berry Street in Nowra) – and, finally, illicit or pornographic material (which, for the young bisexual Frank, included Man magazine).

But this was all largely done in a vacuum, because Nowra in the 1940s and 1950s did not have a local library.

At age 15 Frank had to make a stark choice, which was whether to leave school and take on an apprenticeship in his family’s agricultural manufacturing business, or else to complete high school in order to become a writer. He chose high school, because he knew that in order to become a writer he needed to acquire a broad knowledge of the world.

And for Frank, that meant reading, and to do so broadly and systematically. And the most important factor that facilitated this process – at this crucial moment in his becoming a writer – was the State Library of New South Wales. At the time, the State Library provided a service to deliver books to regional centres. Each month Frank received a cardboard box of books on the train from Sydney. It allowed him to read books otherwise unavailable to him in Nowra, unsupervised by parents or school. And he chose books on every subject, from history, psychology, sociology, economics, political theory, philosophy, as well as literature. This reading also introduced Frank to what became a central obsession with the history and impact of communications media and technology, that would underpin his later advocacy for copyright and author’s rights generally as they become threatened by new media environments.

In the 1960s, when he lived in Sydney, Frank continued to be a regular user of the library here, but mainly this was as background to his intellectual work, for his lectures, his journalism, and his non-fiction writing. But in the early 1970s, Frank began writing his first feature film, Between Wars (1974), and, at the same time, his third book of stories, The Electrical Experience (1974) – both set on the South Coast, during the period between the first and second world wars. And so, for the first time, his writing of fiction required historical and archival research. And once more he turned to the State Library.

For The Electrical Experience, it was here he read through the history of soft drink and cordial manufacturing in Australia, which he placed in the broader context of our technological development. He even began working on a non-fiction companion work to be called, A Technological History of the South Coast. For the film script, it was here where he combed through medical journals from the 1950s and 1960s, looking at obituaries for individuals in the medical field who had died during that period, and who seemed unconventional for the times. He then worked backward through the archives, tracing the arc of their careers in Australia, amalgamating these figures into a single, fictional character – to become the protagonist of his film.

The central historical figure he found during this research was Reginald Spencer Ellery, a controversial Australian psychiatrist and author, who died in 1955. Frank also read Ellery’s 1945 book, Psychiatric Aspects of Modern Warfare (1945). Importantly, Ellery was an advocate of the League of Nations. And so it was in this book – amidst this research – here in this library – where the seeds were sown for a project to write about the League of Nations that came to dominate much of the second half of Frank’s life.

The point of this story – and why I am telling it to you today – is because literary biographies tend to focus, for obvious reasons, on what their subjects wrote. After all, it is what they wrote that made them significant enough to have a biography written about them in the first place. But I would argue that it is also through their reading that made them the writers they would become. And so – for me, at least – literary biography is as much about reconstructing the reading lives of our great writers as it is about reconstructing their writing lives. In practice, the two are inseparable.

And this shared culture of reading is also what provides the fundamental common ground between the subject of such literary biographies and us – the reading public. After all, it is through reading what the subject wrote that we are able to make the argument that their life and works are significant enough to have a biography written about them. But it is only through reading such biographies that we are able to consider the full scope of that argument. But even this is only a means to an end. Because – for me – the main purpose of a literary biography is, first and foremost, to provide enough background to encourage people to read or re-read anew the subject’s works for themselves.

A biography is not a substitute for doing so.

And Frank Moorhouse produced an extraordinary body of work. All of his fiction is connected, his many books – from his first in 1969, to his last in 2011 – share characters, histories, and experiences, narrated across generations, across stories, across books, together covering much of the 20th century. It’s really one big book, told in many parts, kept vital through the use of the discontinuous narrative form. It is, in sum, an attempt to re-imagine the very foundation of Australia’s cultural history, and from that new foundation it is a call for us to re-imagine our social arrangements and our political activities anew. Frank’s fundamental claim is that the basis of a national culture is not the capacity for war, but the capacity for making and sustaining peace; it is not about internal conflict, but about building consensus and a politics of ongoing negotiation.

In this, Frank’s books all add up to one of the most sustained feats of critical imagination in Australia’s literary history. And yet Frank is given little credit for this achievement. The literary ambition in enormous, but we have not yet begun to find its measure.

I mentioned earlier Frank’s lifelong intellectual obsession with media and communications technology and their impact on our public culture. In the 1960s, even before his first book had been published, he was concerned about the impact of emerging technologies on the fate of literature. And on the public infrastructure that supported literature. His famous copyright court case in the 1970s was very much concerned with these questions – the photocopy machine as forerunner of Google. In his final years, he spoke out about the impact of the internet, and on the threatening potential of Artificial Intelligence.

What I’ve concluded from that line of inquiry is that in the current moment, literary biography also takes on an additional purpose and responsibility, which I can only see becoming greater in the future. In reconstructing the long, slow process by which Frank developed as a writer, it has become clear that there are no shortcuts in making literature. And there are no short-cuts or substitutes for reading literature. There are no efficiencies to be gained by outsourcing our imagination to generative AI. Literary biography is a record and account of the all-too-human struggles and triumphs that go into creating works of literature; it is a testimony to the value of literary effort, and how literature is fundamental to the value of our public culture, itself predicated upon such ongoing human effort.

And that literary effort – that long, slow process of becoming a writer, of becoming a reader – begins in childhood. But more importantly, this human potential is only realised against the background of a public infrastructure that supports literacy, the value of reading, and the free circulation of written materials. When we pass over an author’s reading life, we are passing over those pre-conditions that made their writing life possible; we are taking for granted the very infrastructure that necessarily supports our literary and public culture. And so we risk losing them.

And if literary biography is concerned with reconstructing the human effort behind our works of literature, it can’t just be the story of an individual author and their individual efforts, but it must also tell a broader story of a culture and the efforts of many individuals, over many generations, in creating, maintaining, and defending, our necessary cultural infrastructure – central among this are our libraries and archives.

For what it’s worth, this biography is an invitation for us to follow Frank Moorhouse in contributing to that ongoing effort.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter as it will allow me to write this newsletter more frequently, and pay for whiskey and books).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

On Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths

1. With the recent publication of my book Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths, I thought it important to take a moment to reflect on the project, particularly as it is an ongoing concern. This book is the first in a projected two-volume cultural biography of