In April I gave a lecture at the State Library and Archive of Tasmania, the text of which is below. Enjoy.

1.

What follows will seem haphazard, disconnected, and a little disorganised. But that’s because it is. Ostensibly concerned with the writing apprenticeship of Frank Moorhouse, there will also be several seemingly unnecessary asides regarding other authors, and various other digressions, as I grope toward making a larger claim about the life of writers more generally.

The through line that tries to hold all this together is an idea that I am referring to as ‘literary effort’, by which I mean those aspects of a writer’s life that are often hidden from public view, when they are endlessly writing, rewriting, and trying (and often failing) to get their work published. It is as much about the starting and abandoning of projects as it is about completing and publishing projects. It is about the logistical and material structuring of a life around earning a living while simultaneously carving out time to write.

It may be best to try to define what I mean by this phrase – ‘literary effort’ – by giving you a discrete example. This is the only way to do so because – to my mind, at least – ‘literary effort’ is a set of concrete practices rather than an easily stated abstract concept – and the repertoire of such practices differs from writer to writer; but it also differs for each writer, from project to project, depending on various material circumstances the writer finds themselves in, and the particular literary demands of the projects they undertake.

The example I offer by way of introduction is Jack Kerouac’s novel, On the Road. From this we will be better placed to then take a more expansive look at how ‘literary effort’ plays out in the early life and work of Frank Moorhouse. As I’ve only published the first of a two volume biography of Frank – and I am still allegedly writing the second volume – then that more expansive view will necessarily be provisional and unfinished at this stage. The briefer Kerouac example at least has the virtue of being more self-contained and complete.

2.

[Note: this section is ostensibly a summary of a piece previously published, which you can read in full here]

The conventional view – which many of you may already be familiar with – is that in 1951 Jack Kerouac wrote On the Road in three weeks, on a continuous scroll of teletype paper, high on Benzedrine; the outcome of an activity he characterised as ‘Spontaneous Prose’, which emphasises speed over deliberation, and that the first draft is the best draft; a pure literature, without need of revision.

Almost none of this conventional view is true, however. The reality is very different – and, for me, at least, much more interesting.

In November 1948, Kerouac began work on what he called his ‘road novel’, based on his experiences on the road. But this project would take him three and half years, and five distinct manuscript versions, to finally complete. What is now known as On the Road is only the fourth version. The final version was only published in full posthumously, as Visions of Cody.

Kerouac worked on the first three version of the novel from November 1948 until March 1951. He even wrote one in French – his first language – to overcome the limitations of English. The first version was a conventional realist narrative structure, from the point of view of a protagonist that drew in large part on Kerouac’s own experiences.

By March 1949 Kerouac had abandoned that first version and started again. In this second version Kerouac rejected the conventional realist mode and built the narrative around a spiritual quest. He decentred the protagonist from the first version, making him the narrator that focused on a second character; a similar narrative dynamic that plays out with Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. This version more consciously grounded the narrative in literary history, drawing on old texts such as Spencer’s The Faerie Queene and Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress.

Kerouac became dissatisfied with this version, and through re-reading the novels of Herman Melville (Moby Dick, etc), Kerouac attempted a balance between the naturalistic and the spiritual. This created a third version of the novel, which he worked on from February 1950. He took many additional notes during this period, trying to link particular characters and events to archetypal mythologies.

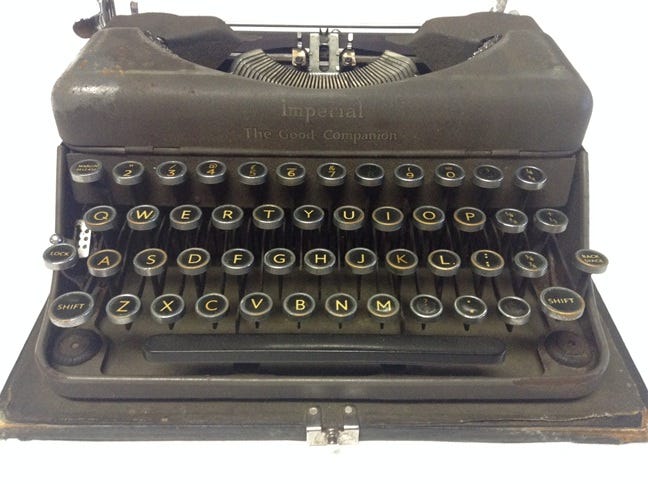

But once more he had become stuck, the links between type and archetype were too forced. He needed to break through and just get a complete rough draft done. It was then, in April 1951, over the course of twenty days, that he was able to finally sit down and type out what became the fourth version of the novel. He used a roll of tele-type paper – that much is true – so that it could be fed continuously through the type-writer without disrupting his concentration.

Here we can dispel several falsehoods surrounding what actually happened when Jack Kerouac sat down to write for those three weeks.

First, although it is a considerable feat to write a 120,000 word manuscript in only 20 days, it is not an improbable feat. Kerouac averaged 6000 words per day, but he was a very fast and accurate typist, averaging 100 words per minute. That means he only needed to work for one hour per day. Of course, he worked longer than that, which means that he probably wrote slower, had breaks, deliberated, but still managed to keep the momentum moving forward.

Second, Kerouac did not write on Benzedrine. He had once tried doing so, but found what he produced was nonsensical. In writing the scroll draft of “On the Road”, he drank coffee. But this was not such a frenetic activity as has been largely assumed. It was driven by inner discipline rather than externally sourced stimulants. He even worked to a daily outline and structure of events that he wanted to get through each day; drawing upon an already established general conception of the whole work, a high degree of organization, and pre-planning.

Third, Kerouac had already worked on three versions of the novel over the past two years. He had lived the raw material, still fresh in recent living memory; he had kept a journal while on the road, wrote long letters and notes about it; and he received long letters from friends who shared the experience. He had worked over this material many times already before he finally sat down for that twenty day period to once more write it all out – for the fourth time – something which he could only do because of this prior effort.

Fourth, the main reason Kerouac was psychologically able to complete this task was because when he sat down that April it was to undertake what he planned as a compositional exercise only. This was never intended to be the final form of the novel. That pressure removed, he allowed himself to write more freely.

Finally, almost immediately upon finishing this exercise, in May 1951, Kerouac spent a month retyping the scroll onto standard paper, revising the text, breaking it into paragraphs, chapters, and sections. Technically, this is not the fifth version of the novel at all, but simply a revision and tidying up on the fourth version.

You will notice that there has been no mention of ‘spontaneous prose’ in the composition of On the Road – for which it is most famed – and the simple reason for that is because Kerouac did not develop this technique until October 1951 – five months after he had already written and revised the scroll version of the novel.

That technique coincided with the fifth and final version of the novel. What eventually became known as Visions of Cody was written over a five month period, from October 1951 to March 1952; which, at the time, Kerouac considered to be the true and final version of “On the Road”.

It took another five years before the novel was published, however. The publisher rejected the Visions of Cody manuscript and chose instead to publish the prior, revised scroll version. The media conflated ‘spontaneous prose’ with the three-week writing stint in 1951, and so a legend was created that does not tally with historical reality.

From my point of view the difference between the conventional view of the writing of On the Road and the more realistic, historically accurate view is that the popular view removes the fundamental experience that literary effort played in the writing of the novel.

Omitting such effort from our understanding of On the Road does a disservice to the novel, as a work of literature; it does a disservice to Jack Kerouac, and his literary reputation; and it does a disservice to readers – past, present, and future – whose experience of the novel is largely distorted by reading it by the dim light of this conventional view.

This point generalises, to most writers, and to most books, worth their salt. By not considering the effort required to write a literary work we also fail to ask ourselves what degree of effort is required of us in reading such a work. We let ourselves off the hook. In doing so we also avoid the more critical question of whether or not this or that work is actually worth such an effort.

And that absence of judgement does a disservice to our literary culture. In Australia, it does a disservice to our writers, to our readers, and to our literature.

It is in this broad context – and with these questions in mind – that I have approached the life and work of Frank Moorhouse. And the biography is an invitation for you to do the same.

3.

I recently gave a talk at the National Library of Australia. They hold Frank’s papers, from age 12, up to and including the publication of his first book, Futility and other animals, in 1969 – at age 31. That talk focused on Frank’s juvenilia. The term ‘juvenilia’ is used to describe the writing done as a child and adolescent – usually up to the age of about 21. This forms the background to their later, more mature or adult works.

There is a period that overlaps this, however – and extends beyond – that is referred to as a writer’s ‘apprenticeship’. It is this broader period I want to focus on tonight, in relation to Frank Moorhouse. But as Frank’s apprenticeship began when he was 11 years old, this necessarily covers also his juvenilia, in the 1950s. So I will need to briefly outline – without repeating too much of the detail – of that previous talk on juvenilia [which you can read in full here]. I will then examine Frank’s more mature apprentice works in the 1960s. But I will recast this entire discussion in terms of what I am referring to as ‘literary effort’.

In that previous talk, in order to truly appreciate the value of Frank’s early material, I needed to make a more general argument for why we should value a writer’s juvenilia. The term itself carries negative connotations, as a source of embarrassment that writers tend to abandon or even destroy as a necessary but best forgotten stepping stone to what comes afterwards.

So to make that case I drew on a relatively new field in the humanities called Juvenilia Studies. These scholars have argued for a more positive view of juvenilia that involves considering childhood writings as a body of literature in their own right, and they achieved this through comparing a writer’s juvenilia with the juvenilia of other writers; to examine what is unique to such writing more generally, and to locate commonalities among otherwise distinct writers.

I would argue, however, that there is also a positive aspect to the otherwise negative view of juvenilia. The negative view is based on the assumption that the writing one does as a child is not as good – whatever we may take that to mean – as the writing one does later, when one is older. In other words, that it is through practice that a writer improves. At a very basic level, what I am referring to as ‘literary effort’ drives this improvement. I would also argue that this does not contradict the findings of juvenilia studies. For when we ignore the value of the effort, we lose one of the fundamental supports that gives the outcome of such effort its value. And it is the necessary relationship between an author’s juvenilia, their later apprentice works, and their more mature or established works, that brings this broader value into sharper focus.

Now Juvenilia Studies points out that when we look for literary representations of childhood and adolescence our attention tends toward a literature written about childhood that is written by adults. Juvenilia Studies argues that this overlooks the possibility of a literature written by children, and of recognising the child’s expression of their own subjectivity and authenticity.

I agree with this. But I also want to make an obvious point that when adult writers write about childhood they often draw upon their own experience of childhood; that something of this earlier subjectivity remains within the adult writer’s literary imagination and can be recovered – to a degree.

One of the most canonical examples of this, of course, is James Joyce’s A Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man. It was published in 1916 when Joyce was 34 years old. There is an earlier attempt at writing this same story – called Stephen Hero – that Joyce wrote between the ages of 22 and 24. Joyce himself considered this an apprentice work, and treated it as such, attempting to destroy it by fire, but it was rescued and posthumously published.

But which is the better account of adolescence? A Portrait of an Artist is technically a more accomplished work. But an argument could be made for Stephen Hero as being a more authentic, more emotionally resonant account of the same experience. As a writer develops in technical skill, what do they gain, and what do they lose, by also (hopefully) developing emotionally out of adolescence? But at the same time, what do they retain of those earlier experiences, unshadowed by adulthood?

If I could be indulged for a moment longer, I want to briefly make the case for an author other than James Joyce that has produced a better account of a portrait of an artist as a young man – the work of mid-20th century Italian-American author, John Fante, and his quartet of books on the childhood and adolescence of an aspiring writer, Arturo Bandini.

John Fante’s final book, after writing 6 novels and numerous short stories, was called Dreams from Bunker Hill. It is also the final Arturo Bandini novel, where our hero is still only in his early 20s, and still struggling to be a writer, having only one short story published. This is the final paragraph of that novel. There is a reference to a real novelist, Knut Hamsun, a Norwegian author, whose 1890 novel, Hunger, was also about a struggling author. Fante’s final book ends like this:

I stretched out on the bed and slept. It was twilight when I awakened and turned on the light. I felt better, no longer tired. I went to the typewriter and sat before it. My thought was to write a sentence, a single perfect sentence. If I could write one good sentence I could write two and if I could write two I could write three, and if I could write three I could write forever. But suppose I failed? Suppose I had lost all of my beautiful talent? … I had seventeen dollars in my wallet. Seventeen dollars and the fear of writing. I sat erect before the typewriter and blew on my fingers. Please God, please Knut Hamsun, don't desert me now. I started to write and I wrote:

`The time has come,' the Walrus said, `To talk of many things: Of shoes — and ships — and sealing wax — Of cabbages — and kings —'

I looked at it and wet my lips. It wasn't mine, but what the hell, a man had to start someplace.

What is remarkable about this – really his final word – is that Fante is able to recover that adolescent experience of starting out. He captures that impulse to write, even when you do not yet have anything original to write about. It is the compulsion of form, even when you do not yet have the experience to substantiate it. It is this process that Juvenilia Studies seeks to explore and reconstruct, as it is happening. Just as it is the literary effort required to do justice to that impulse to write that is of interest to me.

4.

Juvenilia Studies has examined various 19th century child writers, out of which we can discern a general schema of development shared by many child writers. I will only offer a few examples here for context.

First, it begins in physical play, the acting out of scenes from books or stories that a child has read or has been read to. The Brontë sisters, for example, as children, playacted scenes from historical stories derived from Sir Walter Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather.

Second, child writers learn through imitating the books and periodicals found in the family home or given access to at school. Continuing the playacting and physical activity of earlier forms of storytelling, these children not only write, but they also make their own family newspapers or books.

Virginia Woolf, aged 9, for example, made the “Hyde Park News”, a family newspaper that ran into more than a hundred issues. Here the child writer learns through doing: the work of editing, reviewing, designing, illustrating – the act of physically making a newspaper or book.

Third, through imitation of what they are reading, child writers also channel and express their ambition. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, for example, the 19th century English poet, at age 13, wrote an epic poem in imitation of Homer. She was asserting her ambition.

But through this process of imitation, the child writer eventually develops their own critical thinking. A process of differentiation begins, within which individual style, individual concerns, unique to the child, develops. It is through this process of imitation and differentiation – and the effort that accompanies this – that the adolescent writer sets out on the path to become an adult writer, and (hopefully) to begin producing more mature, original works of literature.

In my talk at the National Library I go into this in far more detail, but what I’ve said here is enough to sketch how this shared schema underpins Frank Moorhouse’s own childhood and adolescent experiences.

Like the Brontë sisters, Young Frank play acted. At primary school in Nowra, on the New South Wales South Coast, in the 1940s, Frank Moorhouse would play act scenes from the stories about Gallipoli he was taught in school. He also playacted at making a newspaper. At Wollongong Technical College, in the 1950s, Frank participated in making an actual student newsletter, where he also wrote stories and essays. At Nowra High School he started his own student newsletter, with himself as editor. This newsletter was also a ploy to work on a project with his high school sweetheart, Wendy Halloway, and when he left for Sydney to work on a real newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, his fantasy was always to edit a country newspaper with Wendy as his wife. Before he was 20 years old, this had come true – like Virginia Woolf, his childhood playacting, his adolescent fantasies, at making his own newspaper, were a rehearsal for achieving the real thing.

But where Frank was very much a child of the 20th century – and this is where he differs from child writers from the 19th century – is that although Frank grew up with books and newspapers and periodicals – models to be imitated – he also grew up with cinema and radio. These also provided models of imitation.

The first story Frank wrote, when he was 11 years old, was one Saturday, after seeing a Western film at the Roxy Theatre. Afterward he wrote out the story he had just seen on the screen. This is an example of what John Fante was evoking: that first impulse to write, even when you don’t have anything original to write about. It is the form and the narrative that grabs you initially, rather than the content or the story. For Frank it was the effect of experiencing that story that captured his attention; the thrill of the experience – and he wanted to recreate that experience for himself in his own writing.

Frank’s first encountered short stories in The Australian Women’s Weekly. These became the initial models for his own stories. But these models quickly evolved as his reading and writing evolved. Like Elizabeth Barrett Browning, through imitation, Frank asserted his ambition. In middle school, for example, he rewrote Shakespeare’s play, As You Like It. This is Frank, age 14. He states: ‘It always puzzles me to understand why teachers say that Shakespeare is England’s greatest writer. So I, being a benevolent humanitarian, have decided to write, on behalf of our honourable and esteemed system of education, a modern and up-to-date edition of Shakespeare’s work.’

But here we see also the beginning of this process of critical differentiation, freeing himself from his earlier models of imitation, in order to become his own writer. Frank marked this in High School Frank by writing an ill-advised letter to the editor of The Australian Women’s Weekly. We know that Frank had submitted one of his stories to that magazine, and was rejected. But it is unclear if that was before or after this letter. Or worse, this could possibly be the cover letter he used to submit his own story.

In 1955, The Australian Women’s Weekly published a short story by Frank Shew, an 18 year old Victorian. The story was called “Mr Blogg Goes Home”. 16 year old Frank Moorhouse took exception to this story, and so wrote:

Dear Madam, The Women’s Weekly have started something in this Teenage short story section which had been lacking for some time[:] that of encouragement to young Australian Writers. But I consider that the printing of the short story by Frank Shew was not fair to the author or to the readers of the magazine itself.

The story was not of printable standard. It lacked originality or freshness. The story was overloaded with coincidence…

Frank then proceeds to list all of the problems with the various plot points in the story, using terms like ‘hackneyed’ and ‘unrealism’. He then concludes: ‘Though I am by no means a second Maupassant or O. Henry I do think my criticisms are just and that my effort at a short story is at least better than Frank Shew’s even if it is not worthy of printing.’

Fortunately, Frank stopped writing letters like this, and in 1958, when he was 19 years old, he had his first published short story in Southerly journal – called “The Young Girl and the American Sailor”.

I asked earlier: As a writer develops in technical skill, what do they retain of those earlier experiences, unshadowed by adulthood? Around this time Frank described in his journal how writing makes him feel:

i must express the inner excitement i feel

after i have written a short story

i get up and walk around and around

...

i lose all self consciousness

and a feeling replaces it

i am inclined to strut

i feel as though the story was a part of me

and after great pain and effort i have torn it

away

...

a gladness that the piece of me has been removed a pride in the place removed

and a relieved happy feeling in my self

We saw earlier how John Fante, at the end of his largely unsuccessful writing career, was still able to tap into that youthful experience that initially motivated him to write. What makes John Fante’s example more poignant is that Dreams from Bunker Hill, his final novel, was dictated to his wife, because Fante could no longer physically write or sit at a typewriter. Because of his diabetes he was at the time blind, and bedridden, his legs amputated. And yet, under these harrowing circumstances, a 73 year old John Fante could still evoke the feelings associated with the adolescent desire to begin writing.

And what Frank suggests here in his journal is how that inner excitement and joy that first motivates a child to write continues to motivate as the writer develops in technical skill and experience. With the publication of “The Young Girl and the American Sailor” at age 19 we catch a glimpse of Frank developing out of a period of juvenilia, but still operating very much within that period of his writing apprenticeship. He’s published but not yet established.

During the years 1958-1962, he works as a journalist and newspaper editor, gets married, and has his second short story published – but he was struggling to find further acceptance for his stories. He returns to Sydney, his marriages ends, and although he has found full time employment outside of journalism he finally extricates himself from this second job, so he can focus – for the first time, full time, on his writing. What follows, from 1962 to 1968, is an intense seven year period of writing and increased public engagement. One of the results of which is his first book being published in February 1969.

What I want to focus on here is a close reading of the story ledger that Frank maintained throughout this period, where he listed all of the stories he has written – when he finished writing them – where and when he submitted them to various publications – and both the rejections and acceptances he received. I would argue that this can be read as a catalogue of Frank’s literary effort.

5.

So between 1962 and 1968 Frank wrote 50 short stories. One way we could consider this is to say that Frank wrote on average 7.14 stories per year. But that is far too abstract and doesn’t really tell us anything concrete. And certainly nothing about the effort required to write 50 short stories. So let’s try another way.

Each story underwent at least six drafts. Each draft was retyped in its entirety before moving on to the next draft, incorporating Frank’s handwritten revisions at each stage. In this, Frank followed a general plan, and he actually kept a checklist of what he had to consider during each draft.

The first draft was written directly on the typewriter. The second draft was a general revision; it was then retyped. The third draft repeated this, but Frank focused on character development and story consistencies. He then put the story aside for a week or two, what he called a ‘time lapse’, before revisiting it afresh.

The fourth draft focused on key incidents, dialogue, and on removing what Frank called ‘parasite sections’ – characters, sentences, and plot redundancies otherwise unnecessary to the story. The fifth draft considered spelling and punctuation, and Frank would check his prose for what he called ‘tiredness’ or ‘clumsiness’. After another ‘time lapse’, he did a final revision and produced a final typed version.

Frank didn’t like to think or talk too much about the creative process because he felt that it risked making his work too cerebral. He didn’t want to question where ideas for stories came from or what stories mean or are about, because he was worried that they would dry up and he'd stop having them. He did state, in a letter in 1968: ‘I sometimes become sweaty and fearful when I cease being the hot creator (say in the first draft) and in a later stage of the same work become the cold editor-reviser. I wonder what sort of damage the editor reviser is doing to the work.’ You can hear echoes of Kerouac here – an author Frank was very much familiar with.

Earlier I noted the relationship between juvenilia, apprentice works, and mature works, and the degree to which the play and spontaneity of this earlier stage is not lost but is rather carried over into these later stages, even as they also progress is technical skill. I want to suggest here that for Frank – and this point generalises to most writers – these stages that play out across a lifetime also plays out within each work they produce across that lifetime, from the playful and spontaneous first draft – the hot creator – through to the more mature, more technically adept, final version – the cold-editor revisor; from the juvenile writer to the mature author, over the course of each work. We’re always starting again, as if from scratch. The best we can hope for is that the final version still retains that initial spark that initiated the creative process in the first place. And that becomes the internal measure for each work against which revisions are shaped. That process is also part of what I would call ‘literary effort’.

There is another way we can consider the effort involved in this practice. Frank’s stories were between 6 and 16 typescript pages in length. That means that for each story – working through the six stages of drafting – Frank typed 36 to 96 pages. Or between 1800 and 4800 pages, in order to complete all 50 stories.

Even as I say these numbers out loud, I know they don’t mean anything. What I am groping for is a way to indicate the underlying activity that produced them. The physical activity of sitting at a desk, writing. It is the hours upon hours required to produce this number of pages rather than the pages themselves that matters. Literary effort is often overlooked because it is unquantifiable. But it is not ephemeral, because literary effort is also a physical effort. And that has physical consequences. A frequent refrain in Frank’s letters throughout his life is that he apologises for not replying sooner because after a day writing he is too physically exhausted to keep up with his personal correspondence. We can suggest measures for that activity – number of pages, number of words, number of hours – but these always fail to account for the accompanying mental and physical exhaustion. But that is part of what I want to consider.

Earlier I mentioned an average – that Frank wrote 7.14 stories per year, or 257 to 685 pages each year, over this seven year period. But Frank didn’t write that consistently. For two of these years, 1962 and 1968, Frank only wrote 2 and 3 stories, respectively. For another two of these years, 1964 and 1966, Frank wrote 12 and 13 stories, respectively.

But this does tell us something about the broader material context of literary effort. The years that Frank wrote fewer stories were the years he was working full-time – as Secretary of the Workers Educational Association, or as a journalist at the ABC – and the years he wrote more stories were the years he worked less or not at all. But even here, it was on the money saved during the periods he worked full-time that covered the costs of living for the periods he was writing more. And those periods were foreshortened by the money running out, and Frank needing to return to paid work.

6.

When we think of literary effort, I think we should consider this broader material context: consciously structuring one’s days and weeks in order to carve out the time to write from the time needed to earn the money to buy the time to write. For parents – particularly mothers – this involves also buying the time to write through paying for child care.

The physical and mental effort exerted in whatever job that is done – in order to earn money to buy the time to write – becomes the financial means to that literary end; and so is also very much part of what I am calling literary effort. We tend to try to keep them separate, but I would argue that this would be a mistake.

And yet, I want to stress that literary effort is not reducible to economic terms. I intentionally chose the word ‘effort’ rather than ‘labour’ or ‘work’ in order to show that although there is an obvious (and obviously inadequate) economic component to what writers do, such effort often surpasses whatever economic return a writer may receive. But the flipside of this is also important to keep in mind: that the value of literature to our society is more cultural than economic. That said, we should not lose sight of the fact that there remains a stubborn economic component to such effort.

Rosemary Dobson, for example, worked variously as an art and art history teacher, as a proof reader at Angus & Robertson, and as a printer – which supported her while she wrote poetry. Likewise, David Foster worked as a motorcycle postman. These jobs were not something separate, but integral to their broader literary effort.

One goal, for many, is to be a full-time writer; that is, that the money earned to free oneself from necessity comes from writing itself. This was very much Frank’s goal in the 1960s. For others, however, it may be about striking an equally elusive balance between (paid) work and (unpaid) writing, or writing that pays, but not enough (never enough) to keep writing without a subsidiary income.

7.

So far we have only considered the effort Frank put into writing each story, and the effort he put into creating the material conditions to allow him to write. But Frank was also trying to have his stories published. This is where his story ledger adds a further dimension to his literary effort.

Of the 50 stories he wrote during this period, Frank had 29 accepted for publication. That sounds pretty good: a 58% publication rate. But in order to achieve that he made 140 submissions to various publications. This suggests an administrative aspect to literary effort. Frank had to type out 140 copies of his stories and post them to various publications. That meant an additional 840 to 2240 pages of typescript – as well as 140 cover letters – during this seven year period. And he maintained a ledger to keep track of all of this.

But that administrative activity is freighted with an accompanying psychic burden: being rejected. In getting 29 stories accepted for publication, Frank received 111 rejections: 21 of his stories were deemed unpublishable. In reality, Frank had a 20% success rate (submissions versus acceptance). Only 1 in 5 of his submissions resulted in publication. Which means 4 out of 5 submissions resulted in rejection.

We’ve already noted a positive emotional component to literary effort – the ‘joy’ or ‘inner excitement’ that for Frank accompanies writing a story – but there is also this negative emotional component, associated with rejection. Recall Frank’s adolescent response to The Women’s Weekly – anger.

During the 1960s, Frank noted also feeling heartbroken and disheartened at rejection. He still maintained anger, however, referring to editors of literary magazines as ‘stupid shits’. We are reminded here, of course, of Gwen Harwood’s acrostic poem, ‘FUCK ALL EDITORS’. We tell that story as an amusing literary anecdote, but we don’t consider what that was an emotional response to: how it was related to the unrecognised, unacknowledged literary effort that went into creating the rejected work in the first place. As Albert Camus wrote in his n

otebook in response to a published criticism of his first published novel: ‘Three years to make a book, five lines to ridicule it, and the quotations wrong.’ For when a writer fails to get published, fails to get that contract, this grant or fellowship, or that prize or award, it is felt keenly as a wholesale rejection of that prior effort.

But rejection can also be a learning experience, especially when one doubles down on one’s subsequent efforts. In the 1970s, Frank wrote a letter to Stephen Murray-Smith, the editor of Overland journal. Overland had only published Frank once, ten years earlier, but had since rejected 5 more of his stories. But this is the opposite type of letter to what Frank had previously written to The Australian Women’s Weekly. I quote: ‘I was guiltily surprised to find how much encouragement you gave me in the early sixties and the trouble you took to write notes rather than straight rejections. I now of course, realise that the rejections were correct judgement which at the time (and in the comfortable illusions of memory) were thought to be mistaken. I’d like to thankyou – you were good at handling arrogant, and vulnerable, young short story writers.’

The flipside of rejected works, of course, are abandoned works and projects. Oddly, we only consider the final work an author may have unintentionally abandoned at their point of death – the work they left unfinished because they died before completing it – but we never really consider the works and projects that authors intentionally abandon, because they are alive and have other things to do – life rather than death gets in the way.

For example, we take seriously Albert Camus’s unfinished manuscript for a novel called The First Man – the first 100 pages were found with him when he died in a car crash in 1960. But few people know that in the 1940s, while writing his novel, The Plague, Camus also worked on putting together a fictional archive of material – to be published separately – about the plague – news reports, official communiqués, medical reports, sermons, essays, diary entries, letters, etc – all fabricated by Camus himself.

And although some fragments of this remain, the archive itself was ultimately abandoned. But considering this is as important to our understanding of the intellectual life and creative process of Albert Camus – the enormity of his imagination – as are a consideration of his published works and public pronouncements.

Or take, for example, Hannah Arendt. Even before The Origins of Totalitarianism was published in 1951, Arendt had started working on a prequel. She abandoned the project in 1954 – the final attempt bore the working title: “A Book that Can’t Be Written.” And yet, the ideas she worked through in all of these draft attempts became the seeds for work she published over the remainder of her life.

Likewise, in the early 1970s Frank wrote a screenplay called “Maurice Anderson: Printer and Pelmanist”. The title character is a printer, and the story maps industrial and labour changes in the printing industry, rendering Maurice’s job obsolete. The project was abandoned, the script remained unproduced, but the effort bore fruit in a subsequent work, a book called The Electrical Experience, published in 1974 – with the theme of obsolescence being transposed to short stories about soft drink manufacturing on the South Coast. There are numerous examples like this in Frank’s archives. Many of which I will be tracing in the second volume of his biography.

The point is that rejections and abandonments are rarely wasted, but often become the compost out of which other ideas and projects grow. They are fed on, and continue to feed, the literary effort of an author, whose professional career never proceeds in a straight line, but has many turns, unexpected stops, and various cul-de-sacs. But these are not normally given equal weight in the story of a writer’s life – we prefer the edges smoothed out. And yet, an understanding of The Electrical Experience, for example, is expanded by considering the prior effort given to writing the “Maurice Anderson” screenplay. Omitting such rejections and abandoned works, I would argue, overlooks the broader, messier extent of literary effort undertaken by our authors, and so overlooks much of what makes such lives interesting and worth considering in full. Especially when such efforts eventually pay off.

For Frank, in February 1969, he had his first book published. Over the next six years – which, incidentally, takes us up to the end of the period covered in volume one of the biography – Frank published three books. He also wrote several short films, and a feature film, Between Wars. And he became a regular columnist at The Bulletin.

Over this six year period Frank also wrote another 43 short stories (remarkably close to his average for the previous seven years, which indicates, if anything, that Frank maintained his efforts, and did not rest on his laurels). 28 of these new short stories were published. That’s a 65% publication rate. But more importantly, this was on the back of only 52 submissions. So this marks also a 52% acceptance rate. Frank went from 1 in 5 stories being accepted – in the 1960s – to 1 in every 2 stories being accepted in the 1970s.

This was because he had become more established. He had a reputation. This still required literary effort – and, of course, half the time he was still suffering rejection – but he was becoming more justly rewarded for his effort. He had shifted from his writing apprenticeship to being an established author. But it took 24 years to reach that point. And that, ultimately, is the outward expression of this broad notion of literary effort that I am struggling to articulate.

8.

But why is this important? The popular view of Frank Moorhouse, particularly in the 1960s, is that he was hedonistic, drank a lot and screwed around. In the late 1960s, Frank became an editorial advisor for the girlie magazine, Chance. His biographical note described him as being ‘well known as the biggest libertine in the Libertarian movement… More handsome that Norman Mailer and never carries a knife.’ But that was his public image, that in part he cultivated. But for various reasons – which I explore at length in the biography – privately, this was not necessarily the case.

But undue emphasis on those social aspects of his life overshadows the underlying literary effort that also occurred at the same time. It is not really that important what Frank got up to at night, what matters is what he did the next morning when he got up and dragged himself to his desk. It is what Frank wrote and the enormous effort that went into organising and shaping his writing life – and not who he screwed or drank with – that has ultimately established a life that deserves our attention. I would even suggest that what made Frank such an interesting companion, a charismatic personality that people sought out, was the outcome and expression of the literary effort he undertook; an effort that was largely conducted in isolation, out of social and public view. And if we don’t understand what that entails – in all its various aspects – then we will not even begin to understand him or his works.

I don’t think this is unique to Frank Moorhouse. It generalises to most authors of any note. Nothing I have said this evening is original. All of these aspects of the writing life are already known, especially by writers, but these are usually confined to the guild confessional – and there are many more I’ve not been able to go into. But my justification for stating the obvious is that although all these aspects are known – the mental, the physical, the creative, the administrative, the economic, the emotional, and so on – we tend to keep them separate, and to consider them only in isolation. They are also largely conducted in private. My point is that they are all interdependent and we need to consider how they work together, and we need to do so publicly. And that is what I am trying to make the phrase ‘literary effort’ cover.

9.

Furthermore, when we do so we encounter two paradoxes.

First: that although breaking down the various activities that feed into and support the writing life establishes a sort of division of labour, this does not necessarily lead to an increased productivity or efficiencies or specialisation, because these various tasks are performed by the same person: the writer.

And second: that although such effort manifests in a very particular, very concrete set of activities, occurring in specific places, within specific timeframes, it remains largely unquantifiable, and resists all known metrics.

For the record, I do not think these paradoxes are a negative. In fact, I would argue that they are a positive attribute of the writing life. Surely, in our endeavours, the more points of contact we have in reality, the more stable and grounded our endeavours will be. I would suggest, further, that the problem actually lies in overproduction, that there is virtue in the inefficient – with more opportunities for serendipity and discovery – and that we should all be attempting to become balanced generalists, rather than retreating into narrow specialisation.

But I would also suggest that these positive attributes associated with literary effort put writers and their work at a distinct disadvantage in the contemporary world where if it is unquantifiable or of little economic value it is largely ignored.

And yet, I do think this is something that literary biography is uniquely positioned address. Biography is a testimony to the value of such literary effort; it is a record of the all-too-human struggles and triumphs that go into creating works of literature; and an account of how such literary effort – in both writing and reading – is fundamental to the value of our public culture.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter as it will allow me to write this newsletter more frequently, and pay for whiskey and books).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.