5. On the influence of the purge on Camus’ thinking, 1944-1945

Or, how Camus came to oppose the death penalty and political violence more generally

1.

There is a further complication to the temptation to tie the plague symbol too dogmatically to the period 1942-1944, beyond what has already been shown in previous instalments of this newsletter: that Camus conceived and wrote the first version of the novel before this period of occupation, and then during it he was more concerned with elaborating the theme of separation than the resistance, and when he did incorporate material concerning the resistance into the novel it was in order to downplay it, albeit without dismissing its importance. The further complicating factor is, for Camus, not so much the six months he worked for the Combat newspaper prior to liberation in August 1944, but rather the fifteen months he worked for Combat during the immediate liberation and post-liberation period that followed. This period 1944-1946 proved relatively more important to Camus’ overall thinking during the final composition of The Plague, and more influential in shaping the underlying ethical structure of the narrative, than the previous few years of drafting. And when these previous experiences and ideas were incorporated into the final drafts of the novel – including the resistance against occupation – they were revised in accordance with these more recent, post-liberation experiences and critical self-reflections.

It was during this period that what became known in France as the purge began, in both its official and unofficial forms. The purge was concerned with the identification, removal, and punishment of French citizens who had collaborated with the Nazi occupation and the Vichy regime over the previous years: from the heads of government, down through the civil service and magistrates, as well as all industries, including publishing. Intellectual collaborators, writing for particular collaborationist journals and newspapers which were allowed to operate freely during the years of occupation, who promoted, justified, and propagandised for the Vichy regime were very much targeted. Such figures were the public face which provided cover for the Vichy government.

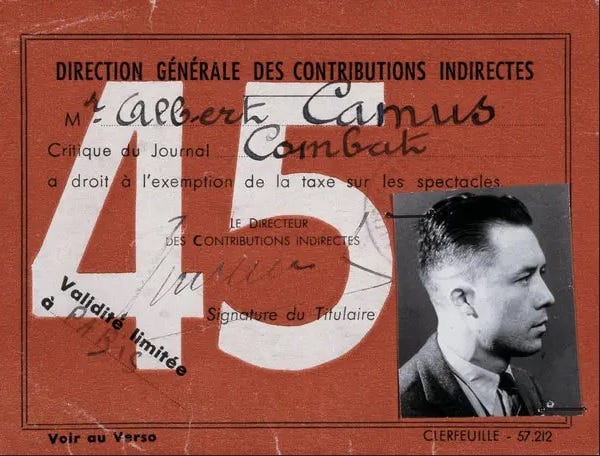

The Combat newspaper, which began in 1941, was a clandestine publication during the occupation, which relied on the underground network of the resistance, with links to allies outside of France. It operated independently from, and in opposition to, the Vichy regime. So it had already accumulated a great deal of moral capital prior to Camus becoming involved in its production. His involvement with the newspaper prior to liberation, however, and the point when he became involved, was unknown to the general public, its staff operating under a shroud of anonymity. But he had, at the same time, personally achieved some public notoriety and fame as the author of The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus, both published in 1942. And he had a play that started its theatre run in Paris in June 1944. So when Combat emerged above ground in August of that same year, in the first days of the liberation, with, for the first time, the actual names of the editorial staff and writers printed in its pages, the moral heft of the newspaper and the intellectual clarity and fame of “Albert Camus”, the author, fused into creating a public figure propelled onto centre stage during the heady period of the purge, and the fierce intellectual debate it reaped. It is this image of “Albert Camus” that would later distort readings of The Plague when it was finally published in 1947.

2.

The initial position of the newspaper, and of Camus personally, was in favour of the purge. The masthead motto of Combat was: “From Resistance to Revolution”. In many respects, the purge was seen as a necessary stage in achieving that revolution, continuous with the previous stage of resistance under occupation. These ideals were also fuelled by the personal memories of close friends and colleagues in the resistance who were tortured or killed under the Vichy regime. Camus was among the many voices that called for swift punishment for collaborators, which in practice included the death penalty. At one point he became involved in a protracted and bitter dispute with François Mauriac, a conservative Catholic writer, but also a resistant, who, in the pages of Le Figaro pleaded for charity, while Camus in Combat responded with calls for absolute justice.

Official courts and rules for proceeding with arrests and trials of accused collaborators were quickly established, but not quick enough for many in the community, who initially took matters into their own hands. During the period of the unofficial purge, groups and individuals acted independently of the authorities to track down other individuals who were known collaborators, or even suspected of being so, who were then beaten or summarily killed. Women who were accused of being ‘horizontal collaborators’ for consorting with German soldiers – often as a mode of survival – were taken out into public spaces, stripped naked, their heads shaven; they were humiliated, beaten, and at times killed.

Even when the official courts were established, due process was not often adhered to. There were also practical problems which undermined the integrity of many of these proceedings. If all the magistrates who served under the Vichy regime were removed from their posts, then there would not have been enough qualified magistrates to operate the courts. So some magistrates who worked under Vichy, and previously judged according to the laws of that regime, including racial laws and laws against resistors, were now sitting in judgement on fellow collaborators – including other magistrates – but collaborators who were deemed in advance by some arbitrary rule as being somehow more deserving of punishment. Jury selection also proved difficult with it being nearly impossible to have juries who did not include victims of the Vichy regime, those who were related to or associated with those who had died or who had been in the resistance. Many jurors had also been in the resistance themselves. What further complicated matters was that those figures who were higher up the chain of command in the Vichy regime, and so were arguably more responsible, were afforded longer court proceedings, at later dates, when much of the initial heat had died down, which resulted in often lighter sentences. Meanwhile those lower on the chain, with less responsibility, were sentenced earlier, and more quickly, and so were more likely to be given the death sentence. All of this led, in practice, to not only an uneven distribution of justice, but more often as not the perpetuation of injustice.

For Camus, it quickly became obvious that the purge was failing and had become largely discredited, the practice being at odds with the intent, justice bleeding into revenge.

3.

The turning point for Camus came in late January 1945 when he was asked to sign a petition to commute the death sentence of an infamous collaborationist journalist, Robert Brasillach. He was a novelist, a literary and film critic for the popular right-wing newspaper, Je Suis Partout. During the 1930s and early 1940s, Brasillach moved from being a French nationalist and fascist, to self-confessed Germanophile and anti-Semite, and finally to Nazi collaborator in an occupied France, writing pro-Nazi propaganda in his newspaper columns, and openly denouncing French Jews. Brasillach, more clearly than anyone, represented those ‘men of betrayal and injustice’ Camus wrote about in an editorial in Combat on October 25 1944. ‘Their very existence poses the problem of justice, for they constitute a living part of this country, and we must decide whether we will destroy them.’

More remarkable still was the fact the petition for Brasillach originated with François Mauriac – although it was presented to Camus via a third party, the author Marcel Aymé. Camus must have wondered why Mauriac would bother getting Aymé to approach him at all, considering his very public position on the purge. Their pubic quarrel was then at its peak. The last editorial Camus had published, on January 11, before receiving the petition, was a response to a direct attack Mauriac had made on Camus, and Camus had replied in kind. But there was perhaps something else. Throughout his journalism Brasillach had heaped insults upon Mauriac, attacking his talent and his relevance, accusing him of being too old, and most notably, since Mauriac’s struggle with throat cancer a decade earlier, which affected his speaking voice, of referring to him in the press as that ‘squeaky old bird.’ Camus must have also wondered how Mauriac’s charity would extend to such a personally disdainful man.

The petition statement which Camus received had requested a pardon for Robert Brasillach’s life on the grounds that his father had already given his life for France. Lieutenant Brasillach was killed in battle on November 13, 1914, before his son was even six years old. Camus himself was a war orphan. His father was wounded in the Battle of the Marne, and died soon after in hospital on October 11, 1914 – one month before Brasillach’s father was killed. Camus was less than a year old and he retained no memory of his father, other than what his family later told him.

Thirty years later, in the chaotic days before the liberation of Paris, when it was clear that the Nazis would soon be overthrown, most collaborators fled the city. Brasillach, however, remained, hiding in a converted maid’s quarters. He was hidden there when Paris was finally liberated, and when the roundup of collaborators commenced, with his name nearing the top of the list. On August 21, 1944, Brasillach’s mother and stepfather were arrested, for no other reason other than the fact they were Brasillach’s parents. His stepfather was soon released, but his mother was held in a prison used to hold women criminals and prostitutes. Three weeks later she was transferred to a prison reserved for ‘horizontal collaborators’. Brasillach’s mother was kept there, amongst other so-called political prisoners, while the authorities used her incarceration as a means of flushing her son out of hiding.

It worked.

When he finally got word of his mother’s captivity, Brasillach turned himself in, knowing full well what was in store for him. After his surrender, his mother was released. Later, after the trial and the death sentence were handed down, it was Brasillach’s mother who first wrote to François Mauriac, pleading with him to intervene on behalf of her son. Camus would almost certainly have disapproved of the state using the mother in order to reach her son, but Brasillach’s response would have also given Camus pause. As Camus had written in one of his lyrical essays in the late 1930s, regarding the code of morals among Algerians: You “don’t let your mother down.”

Mauriac perhaps sensed Camus was wavering on the purge, and that a private, rather than a public approach, would be more effective. It was a gamble that paid off. Camus paced long into the night of January 26, considering the petition, and his own thinking, against the background of the faltering purge, and the previous years of war and occupation. The next morning he signed the petition. He also wrote a letter to Aymé, explaining his decision:

I have always been horrified by death sentences and I decided, as an individual at least, that I could not participate in one, even by abstention... That’s all, and it’s a scruple which I imagine would make Brasillach’s friends laugh a lot. And as for Brasillach, if he is pardoned and if an amnesty frees him, as it must, in a year or two, I want this letter to tell him the following, from me: I did not add my signature to yours for his sake, nor for the writer, whom I consider as nothing at all, nor for the person, whom I despise with all the force that is in me... You say that randomness enters into political opinions, and I have no idea about that. But I know that there is no randomness in choosing what dishonours you.

The petition failed, however, and, on February 6, 1945, Brasillach was executed.

4.

There is a rider to this tale. In January 1948, in a letter to Grenier, Camus relates how during the purge he quietly sat in on one of the purge trials. ‘The accused was guilty in my eyes,’ Camus wrote. ‘Yet I left the trial before the end because I was with him and I never again went back to a trial of this kind. In every man there is an innocent part. This is what makes any absolute condemnation revolting. We don’t think enough about pain.’ It is unclear, however, precisely when this event took place, whether before or after the Brasillach petition. We don’t know if this event prepared Camus for his response to the Brasillach petition, or if afterward it confirmed for him his decision. Either way, what Camus decided at this time was that being horrified by the death penalty was not enough, and that henceforth his political thinking would be guided by a principled opposition to the death penalty, in all its forms, including the use of political violence. It was a position he held steadfast to for the rest of his short life, and which would be enormously consequential in shaping the course of his remaining years, including the final revisions of The Plague.