Reading Aurelian Craiutu’s “Why Not Moderation?” in a moment of uncertain polarisation and partisanship

Or, ‘Political labels be damn’

1.

If there is one point of agreement between those on both the political left and right – progressives and conservatives alike – it is a mutual disdain for political ‘moderates’. Such figures are held to be weak and indecisive, lukewarm in their political passions, and ultimately disloyal. The left dismiss them as being reactionary and hopeless, while the right condemn them for their perceived political cowardice. Both suspect that such figures, at the end of the day, are really closeted advocates for the other side, either through acquiescence or resignation to their opponent’s agenda.

This view, however, is predicated on the child-like assumption that in any given situation there can only ever be two alternatives – and only one can and must be correct.

‘Moderates’ disturb this view by putting the lie to both parts of this assumption. They consider there to always be more than two options in any given situation, and they understand there is no pre-established standard by which to assess in advance which option is correct. And yet, they accept that we must still choose, and we must deliberate upon those choices, and accept responsibility for the consequences. That should be enough for any person who takes politics seriously to want to consider more deeply the question of political ‘moderation’, its history, ideas, and practice. And yet, few have (you can draw your own conclusions from that). But one person who has done much of the heavy lifting for the rest of us over recent years is the scholar, Aurelian Craiutu.

The outlines of his project began with the 2006 volume, Elogiul moderaţiei [In Praise of Moderation], still untranslated from his native Romanian. In 2012, A Virtue for Courageous Minds: Moderation in French Political Thought, 1748–1830 was published – with a long threatened second volume set to cover the period 1830-1900 – which began the process of uncovering a broad and variegated history of this political experience. In 2017, Craiutu published Faces of Moderation: The Art of Balance in an Age of Extremes, profiling several 20th century individuals – ‘representative authors’ – from European and American backgrounds, who, as Craitu states, ‘defended their beliefs in liberty, civility, and moderation in an age when many intellectuals shunned moderation and embraced various forms of radicalism and extremism.’

More recently, Craiutu has written Why Not Moderation? Letters to Young Radicals (2024). It is very much a distillation of his previous books, bringing to bear the historical ballast of A Virtue for Courageous Minds with a focus on individual agency characteristic of Faces of Moderation.

In contrast to the opprobrium and false images projected by ideologues onto the figure of the ‘moderate’, the various chapters of this latest book examine ‘moderation’ as a ‘fighting creed’: a practice predicated upon the political virtues of modesty and humility, civility, prudence, realism and pragmatism. Craiutu addresses the general scepticism (and dismissal) of ‘moderation’ and what its critics tend to (wilfully) miss or ignore. In turn, he rescues ‘moderation’ from caricature and reasserts its practice as an alternative to ideology, an antidote to fanaticism, a limit to moral certainty, and a challenge to political Manichaeism. It is a creed, in other words, for the adults in the room.

2.

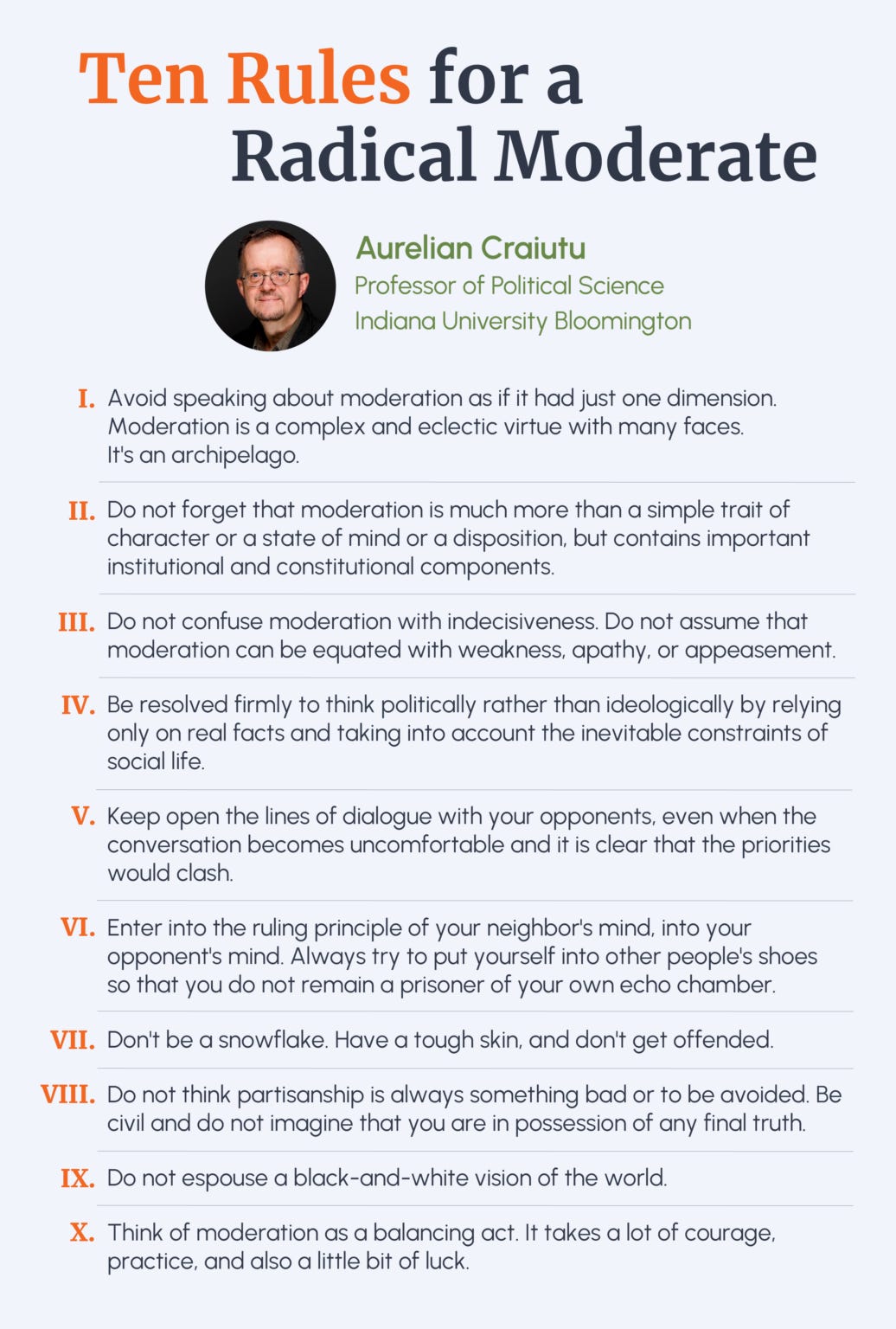

Why Not Moderation? concludes with outlining ten rules for a ‘radical moderate’ – ‘radical’ in the sense of getting back to the root of what political ‘moderation’ is, in practice, concerned with.

I am tempted to suggest an amendment to this list – paraphrased from George Orwell’s rules for writing – which, in this new context, would say something like: Break any of these rules sooner than saying or doing anything outright barbarous.

This link between politics and writing is not arbitrary, however. And what I find most interesting about Why Not Moderation? are the ways it draws attention to the question of form, its own included. This is not to draw attention away from the content of the book. After all, one of Craiutu’s substantive claims is that form does much to constitute the content of any work – just as social forms operate in any given situation, defining the scope of practicable action. In this, Craiutu reminds us of how little effort and attention is usually given to considering the forms of political thought and action, how these shape our political realities, and how we come to understand them. We often do not consider how, through such forms, we come to consider possibilities and select courses of action; or, alternately, how such courses of action are imposed upon us, delimited by ideology, reducing the range of our thought, speech, and the scope of our political will.

Why Not Moderation? is written in the form of short essays, letters, and a series of questions and answers. The common factor is that they are all dialogic, incorporating alternative standpoints into the narrative, as distinct and valid – but also, always, partial. This enacts Craiutu’s main point, regarding a ‘close link between moderation and dialogue’. The imagined interlocutors include ‘Lauren’ – from the political left – and ‘Rob’ – from the political right. So as not to create straw men (or straw women), Craiutu draws on certain left-wing publications – Jacobin, In These Times, and n+1 – to buttress Lauren’s position, while right-wing publications – First Things, The Claremont Review of Books, and The American Mind – are cited to support Rob’s position.

Craiutu’s own narrative standpoint is located outside of these positions, but in dialogue with them – and, as importantly, it provides the conditions for a dialogue between them. Filtered through this narrative form, Why Not Moderation? enacts a critique of, and provides a viable alternative to, the limiting form of political ideology.

Such ideological forms are characterised by being fundamentally monological, righteously dichotomous, and characterised by short-term thinking. In contrast, ‘moderation’ is dialogical, modestly plural, and characterised by long-term thinking. The paradox this comparison reveals is that ideologues – who usually take themselves to be fiercely political – are in practice seeking a cessation of politics; they long for a certain endpoint, a moment of rest and respite after which politics would be no longer required. It is an end-point that reflects the state of political innocence, which marks their prelapsarian starting point, which they are trying to defend, and to reclaim. Political ‘moderation’, however, understands politics to be, as Craiutu puts it, ‘an endless task’. For the world is always in flux, so we, too, must be in flux, but consciously so, and often counter to the welter and waste of the world around us, if only to maintain a relative, temporary stability.

Meanwhile, ideologues desire a world that remains still, where fixed principles can be applied mindlessly, mechanically, and forever.

3.

Of course, one problem with that description is that it threatens to reassert the selfsame dichotomous form that political ‘moderation’ is otherwise attempting to leave behind. It can be all too easily reduced to a claim of ‘moderation’ versus ideology, thus inviting the rest of its formal assemblages to return through the backdoor: the monologue, short-term thinking, and the desire to dominate and bring politics to an end. In other words, it risks turning ‘moderation’ into yet another ideology.

This is not Craiutu’s position, however, and this is precisely what his project seeks to erect a bulwark against in others and to resist in itself. In this, Craiutu is constantly reaching outside this formal, dichotomous constraint, to establish a more independent position, even as he recognises the risk that this language may be misconstrued, that this position may be co-opted back into more orthodox ideological forms, particularly by inattentive readers. In the caveat lector that opens Why Not Moderation?, for example, Craiutu foresees his book being misunderstood in this way. ‘The author will be seen as too far left (and too “woke”) by his ultra-conservative friends, and too far right (and quite “reactionary”) by his liberal readers.’ And yet, elsewhere in the book, he argues:

‘One does not need to be a socialist to complain about the inequalities generated by the market, nor must one be a capitalist to criticise the waste of resources due to flawed welfare and social programs. Similarly, one does not have to be a committed left-wing activist to point out the moral costs of capitalism and its externalities, nor be a right-wing conservative or a committed libertarian to talk about the undeniable material benefits of capitalism and its underlying virtues that sustain economic progress. The center allows everyone to do just that without becoming wedded to a single ideological perspective forever.’

This recalls how Craiutu previously framed the individuals he profiled in his earlier book, Faces of Moderation:

‘The thinkers discussed or mentioned in these pages came from several national cultures (mainly France, Italy, England, Poland, and the United States) and belonged to different disciplines (political theory, philosophy, sociology, literature, and history of ideas). Not all of them identified themselves primarily as moderates; some preferred to be seen as liberals or conservatives, while others rejected all labels. What makes them fascinating and noteworthy is precisely their syncretism as illustrated by their different trajectories and ideas as well as by the fact that many of these thinkers, brave soldiers in the battle for freedom, refused narrow political affiliation and displayed political courage in tough times.’

I would suggest that the problem with that previous description and Craiutu’s attempts to escape it – as with so many of our social and political problems – starts and ends with how we use the language at our disposal. Craiutu himself recognises this, when, in Faces of Moderation, he argues that ‘transcending the conventional categories of our political vocabulary’ is paramount to his project. And yet, I would suggest, that his language often remains squarely within the frame of reference established by these conventional categories, and this picks at the thread of his more substantive and important arguments, which thereby risks coming apart.

Many of the terms used here to describe the experience of political ‘moderation’ – including the term ‘moderation’ itself, which is why I place it in quotation marks – comes from a frame of reference established and defined by the ideologies of left and right. The popular understanding of the term ‘moderation’ – linked also to the language of ‘centrism’ – is premised upon the unquestioned assumption that politics operates along a directional scale from left to right, and that in any given situation, mid-way between these extremes, is the political ‘centre’ – a ‘moderate’, or ‘centrist’, being a person who occupies such a position.

Certainly, some political actors do operate under this thoughtless calculation, hedging their political bets. But this is not the broad experience Craitu is trying to articulate. The experience under scrutiny here proceeds by questioning this underlying assumption, rejecting that scale as inadequate to the task of understanding and organising the complexity of our political reality. And it is to name (or rename) that process that we need a new dictionary.

So, for example, when Craiutu states that ‘[o]ur instinct is to explore and understand what each side says and figure out what, if anything, might be derived from it that has some value’, I would simply add that this also requires being aware that these are not the only options, and that much more is probably left out of ‘what each side says’ – the discovery of additional, new ideas, or the revival of very old ideas – which may also be valuable and worth reconsidering. But this can only begin when we relinquish the narrow framework of ‘what each side says’ – and consider what, in each side, remains unsaid.

This critical process of extraction of ideas from ideology begins by acknowledging that the categories of ‘left and right’ are simply spatial metaphors, not to be taken literally, and not to be conflated with reality – and as such they can be abandoned and replaced with more adequate metaphors. The degree to which a person cannot appreciate this – that cannot distinguish between the metaphoric and the literal in their own thought – is the degree to which that person has abdicated their critical intelligence to ideology. For such a person, the stakes of their political life have reflexively been about assuming a position vis a vis one’s opponents, and not so much with judging or changing political situations. The claim that the mainstream media is biased or untruthful, for example, was once a left-wing notion, but in more recent times it became a central claim of the right; a universal basic income has become one of the arguments pursued by the left, but the idea emerged from 1960s free-market conservatism; in the 1990s globalism was seen as an ascendant right-wing, free market structure that the left wanted to dismantle, but 20 years later globalism is a right-wing canard; the flipside of this being where the right now demands closed borders and the left promote open borders, 20 years earlier, it was the left that demanded closed borders against the right’s promotion of free-trade and global free-markets. Such examples proliferate in what passes as political discourse, this disconnection between vocabulary and reality being the norm rather than the exception.

4.

But if we truly are to transcend the conventional categories of our political vocabulary the first thing we need to do is jettison old terms, establish new ones, and then argue over the rescuing and rehabilitation of particular words which have been otherwise corrupted, distorted or rendered meaningless through misuse or overuse. Such a critical project begins by clarifying the language we use.

I’ve already suggested that many of the terms used to describe the experience of political ‘moderation’ – including the term ‘moderation’ itself and its metaphoric entailments, such as the notion of a political ‘center’ – derive from a frame of reference defined by the metaphors of left and right. This experience has hitherto been defined negatively against these prevailing political dogmas. What is needed now is a more positively defined terminology against which such dogmas are recast as being secondary or derivative. But this would require also reconsidering the terms ‘moderation’ and ‘centre’.

My preference is that the term ‘moderate’ only be used – if it must be used at all – to describe the concrete negotiating and aligning of thought and action to the contingencies of reality, and not used to describe balancing or mediating between the abstractions of two ideological extremes. The emphasis should be on the verb, ‘to moderate’, and not on the noun, as in defining a person as ‘a moderate’, in which the activity of moderating is collapsed into simply the expression of an individual’s identity. For starters, moderation is not circumscribed by an individual, but operates between individuals; it describes how we interact with each other, how we work together – or against each other – to establish an adequate definition for each particular situation we find ourselves in.

As such, moderation – as an activity – does not presuppose a single, fixed position, but suggests instead a multi-perspectival view, a plurality of individual stand-points. In any given situation, some views will be more plausible than others, just as those views may become useful in other situations. Moderation is the process of considering the situation, and the available options, and winnowing down to a workable and always provisional plan of action. It is always provisional because the motive for each decision is born of a particular context, and once a decision is made, once a course of action is initiated, the context will inevitably change, too. And this will introduce new motives, new decisions to be made, and open up additional courses of action to be taken – or not. It is the ‘endless task’ of politics, without a prior state of innocence to retreat into, or a final goal to be reached, whereby all the interim actions will be vindicated.

This is consistent with a metaphor Craiutu has frequently used, lifted from the treatise, The Character of a Trimmer, written by the Marquess of Halifax in 1684/5. As Craiutu describes this, in a recent interview: ‘Trimming is a nautical metaphor that can be applied to politics: trimming the sails of the ship of the state to keep it on an even keel. This is what great statesmen and stateswomen can do. This is what bad statesmen and stateswomen cannot do, which is they cannot keep the ship on an even keel.’

Ideologues tend to misinterpret this metaphor pejoratively, to describe a person who changes with the wind, as if such a person is indecisive or easily swayed. But this misses the context for the metaphor, which is that on a boat at sea, when the wind changes, the crew must shift the sails, in order maintain their course. Far from being indecisive, trimming is a deliberate act; far from being swayed, it is often concerned with going against efforts to knock one off course. Such a misinterpretation suggests a person who has never sailed a boat, or floated a metaphor.

5.

I don’t have a ready-made or final answer to what this new political vocabulary could look like. It is part of that ‘endless task’, to find the right words. It is also a task to be performed in dialogue with others, and not to be predetermined and prescribed. It is task that others have already tried before us, and so we are always entering into an already ongoing conversation or discussion. None of these ideas are new; they just remain unheard.

I am thinking, for example, of Siegfried Kracauer’s essay, “The Group as Bearer of Ideas” (1922), where he offers one way of describing what we lose as individuals when we subordinate ourselves to an ideology, ‘the idea’ which otherwise constitutes the group. ‘Just as the tuning fork is tuned to only one pitch,’ Kracauer states,

the group is completely attuned to the one idea it champions. The moment the group is constituted, everything unrelated to this idea is automatically excluded. The people united in the group are no longer full individuals, but only fragments of individuals whose very right to exist is exclusively a function of the group’s goal. The subject as an individual-self linked to other individual-selves is a being whose resources must be conceived as endless and who, incapable of being completely ruled by the idea, still lives in realms located outside the idea’s sphere of influence. The subject as a group member is a partial-self that is cut off from its full being and cannot stray from the path which the idea prescribes for it.

This distinction between an ‘individual-self linked to other individual-selves’, set against the ‘partial-self’ of the group subordinate to ‘the idea’, is also a thread pursued by Albert Camus, from the 1930s through to the 1950s, as I have stated previously:

Under what conditions, then, should one therefore think and act? This marks one of the most consistent threads that runs through Camus’ work: the necessity of thinking and acting without the prop or support of abstract systems, doctrines, or ideologies, on the grounds that each operates through the false promise of alleviating from the individual the responsibility for their life, and their responsibility to others. This underpins his criticism of the philosophical suicides in The Myth of Sisyphus, and the political nihilists (philosophical murderers) in The Rebel; but it is an idea which he first articulated in 1939. ‘Everything I am offered seeks to deliver man from the weight of his own life,’ Camus states, in his lyrical essay, “The Wind at Djemila”: ‘But as I watch the great birds flying heavily through the sky at Djemila, it is precisely a certain weight of life that I ask for and obtain.’ In 1942, in Sisyphus, he states: ‘I understand then why the doctrines that explain everything to me also debilitate me at the same time. They relieve me of the weight of my own life, and yet I must carry it alone.’ Then, in a 1943 review-essay on the language studies of Brice Parain, Camus writes: ‘What we can learn from the experience Parain sets forth is to turn our back upon attitudes and oratory in order to bear scrupulously the weight of our own daily lives.’ Finally, in 1951, he opens The Rebel, with an attack on the type of person who ‘through lack of character, takes refuge in a doctrine.

Here Camus is rejecting the ‘partial-self’ subordinate to ‘the idea’. Kracauer would suggest, however, that this weight of accepting the ‘individual-self’ is made all the more bearable when we are ‘linked to other individual-selves’ as ‘a being whose resources must be conceived as endless and who, incapable of being completely ruled by the idea, still lives in realms located outside the idea’s sphere of influence.’

It is to such realms as these, occupied by such ‘individual-selves’, that Craiutu is referring to in his own work.

6.

I am thinking also of the work of Hannah Arendt, who, in the 1950s and 1960s, pushes this discussion even further. It is here that Hannah Arendt offers us a vocabulary that begins to shift us away from the terminology of ‘moderation’, albeit remaining squarely within its political form. For example, she uses instead the verb, ‘to regulate’, to describe the political experience of individuals interacting with other individuals in particular situations – reminiscent of Kracauer’s ‘individual-self linked to other individual-selves’. It is an experience which depends, Arendt states, ‘upon our common sense which regulates and controls all other senses and without which each of us would be enclosed in his own particularity of sense data which in themselves are unreliable and treacherous. Only because we have common sense, that is because not one man, but men in the plural inhabit the earth can we trust our immediate sensual experience’ (emphasis added). Alternately, Arendt speaks of checks and controls: ‘In this general understanding, common sense is the indication in the human condition that man exists only in plurality and therefore checks and controls his particular sense data against the common data of others...’

For Arendt, this fact of plurality replaces the language of some narrow political ‘center’ (upon which isolated individuals are said occupy) with a broader, more dynamic and fluid language that describes ‘that realm which western men established as the world of living-together, which lies between us and which therefore we all have in common. The world of common public concern...’ In practice, this works to de-centre our thinking about politics, in two senses: first, it shifts ourselves from thinking that such a thing as a fixed political ‘centre’ exists, and second, it shift ourselves from acting as if we can and should occupy such a position. And what, for Arendt, this shifts us toward is a much more expansive sense of what she calls ‘the world’ that stands ‘between us’: ‘What reveals itself to us is the world which we all have in common, which is between us and at the same time unites and separates us; it is this common world which reveals itself in distinct difference and singularity to each of us.’

For Arendt, this de-centres our political thinking, away from ourselves, as isolated individuals – susceptible to easy answers and comfortable postures of ideology – and toward the possibilities of the world that opens up between us, and of our own plurality. ‘Strictly speaking,’ Arendt argues,

politics is not so much about human beings as it is about the world that comes into being between them and endures beyond them. To the extent that politics becomes destructive and causes the world to end, it destroys and annihilates itself. To put it another way, the more peoples there are in the world who stand in some particular relationship with one another, the more world there is to form between them, and the larger and richer that world will be. The more standpoints there are within any given nation from which to view the same world that shelters and presents itself equally to all, the more significant and open to the world that nation will be.

Likewise, Aurelian Craiutu, although he uses the term ‘center’, he also points to its own redundancy when he calls for a redefinition of such a ‘center’ that ‘does not have to be entirely dependent on what happens at the extremes but can follow a logic of its own.’ A position which, instead, ‘tries to see beyond such dichotomies which are oversimplifications that may further deepen our rifts.’ But here I would risk one more pedantry by suggesting that even this language of ‘beyond’ is flawed, because it is predicated upon permitting that dichotomy to continue to be held as primary, and legitimate, thus reinforcing it even as one attempts to move ‘beyond’.

The real question, I would suggest, would be to consider what is the prior complexity within which we live (and continue to live) before it becomes distorted by the binary logic and simplification of ideology. And then to ask ourselves how we are to deal with that reality; how we are to moderate (verb) our political behaviour to that shared world that opens up between us.

7.

I am thinking also of more contemporary figures, such as the example of Eddie Glaude, who we have witnessed, over recent years, and in real-time, coming to grips with the self-same questions and concerns that have occupied these figures, stated above; questions which Aurelian Craiutu has explored in depth in his own research and scholarship. But where Craiutu speaks of ‘radical moderation’, Glaude has instead invoked the language of ‘pragmatic political realism’, albeit suggesting an otherwise common political form. In a recent statement – which I will close with, as a précis for all I’ve struggled to articulate above – Glaude has stated:

I have embraced what can be called a pragmatic political realism: where certain moral and ethical considerations drive my engagement with the political order. A politics released from the constraints of dogma but motivated by an abiding concern for a more just world – a world in which we stand in right relation with one another. You don’t leave your commitments at the door when you engage the powers that be. Instead, you try, within and outside of current political constraints, to open space for a different kind of imagining of politics. The concern here is less about the appearance of being right (the performance of a certain kind of political virtue) and more about the circumstances of the most vulnerable among us (to reduce the suffering of the least of these as we work for a more just world).

To which he adds, in sum: ‘Political labels be damn.’

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter as it will allow me to write this newsletter more frequently).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.