A brief history of (not) touching art

Or how the apotheosis of sight and rationality has rendered art obsolete

One of the most ubiquitous signs in every museum and art gallery the world over is some variation of the command: do not touch the art. The common assumption – even among those working in these museums and galleries – is that the purpose of this is obviously to protect the artworks from damage – an act of preservation and conservation – and that it is a longstanding tradition. But like most common assumptions which guide our everyday lives, it is neither as longstanding nor as simple as we’d probably like to think; and the preservation rationale was only ever an afterthought.

1.

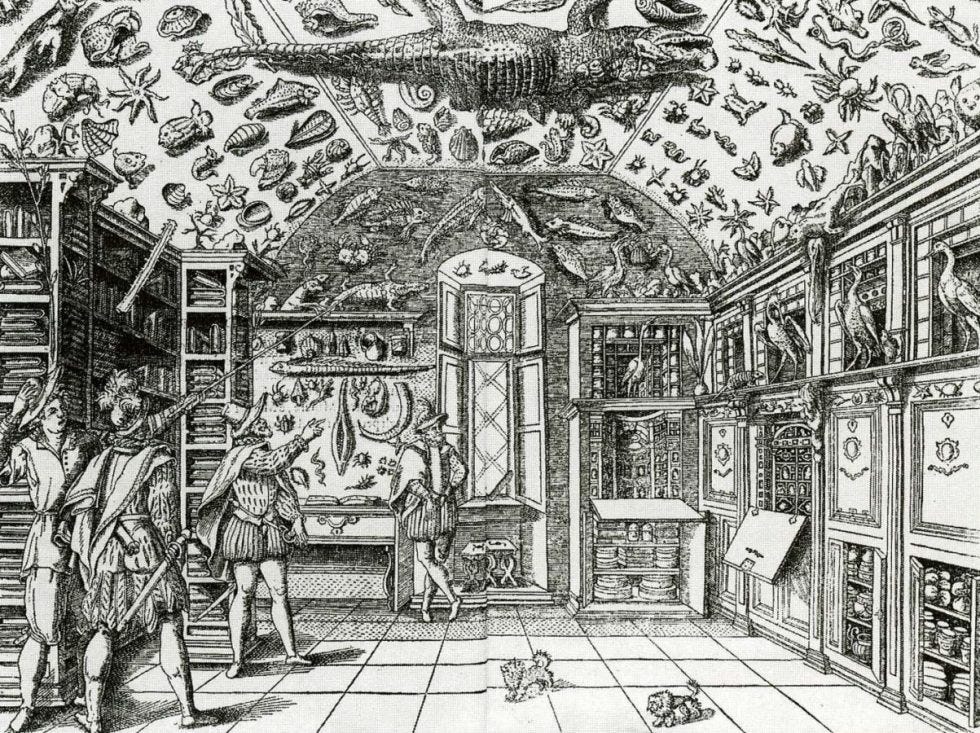

The 17th and 18th centuries was the period of private (rather than the public) museum and galleries, in the form of personal collections, or collections housed by societies (such as the Royal Society). These ‘cabinets of curiosities’ required a ‘wandering rather than a disciplined eye’ (Bennett), in which the sense of sight was not yet elevated in isolation from the other senses, but rather was embedded within an acoustic space, in which touching and handling objects was the norm, both as a prompt to civic conversation; talking and listening to stories about the objects, asking and answering questions about them, and so on.

There was no discernible order to these collections, and so the eye, rather than being pulled away from the collection was pulled into it, ‘caught in a system of side-ways glances between objects whose organization was dialogical’ (Bennett). As an extension of this (albeit elite) civic discourse, private museum tours were often concluded with a meal or with a coffee, usually taken within the collection space, such that the smells of prepared food and drink accompanied the general atmosphere of the collections.

In the 18th century, in private collections, the owner would freely touch what they liked. But it was seen as a courtesy for the host to allow their guests to also touch items. Touching the objects was in part a way of acquiring social prestige: ‘touching with one’s own hands artefacts and artworks which had passed through a succession of distinguished hands in the past.’ (Classen). It was also probably associated with the transferal of semi-mystical power; particularly as many items had royal, religious, or mythological associations, and as such, held a certain cultural aura, which was thought could be accessed through touch alone.

It is worth noting, however, that during this same period, neither owners nor visitors of collections were particularly cognisant of preservation or conservation techniques; either in the way objects were stored, displayed, or handled. There was frequent damage, and also a problem with theft. Some museums were kept locked, not so much to keep people out, but to keep their guests in – until the collector could be sure that everything had been returned to their rightful place, before their guests were allowed to depart.

None of this, however, was seen as reason to desist from touching the art; it was all accommodated into the experience of visiting a museum or gallery. In part, this is because, during the 18th century, touch was associated with certainty, which was consistent with empirical philosophy at the time – such as that of John Locke – and so was used to verify sight: to distinguish between real and fake, or heavy or light, or rough or smooth, and so on. Surface deceptions could be corrected by touch. Sight alone was limited to surface appearance only; touch added depth; but so did, to a lesser degree, taste and smell. Hans Sloane, for example, the founder of the British Museum, used touch – as well as taste and smell – to help classify and describe his collected specimens. It was only later, with the prevalent use of microscopes and telescopes that empiricism itself became more narrowly focused on sight alone, and came to privilege that which could not otherwise be seen by the naked eye – which implied also that which could not be touched by the naked hand.

2.

This legitimacy of touch carried over into the 19th century, but as museums gradually became open more and more to the general public, this legitimacy began to be undermined. In the late 18th century, the British Museum, for example, was open to the public on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Tuesdays and Thursdays were set aside for artists, private patrons, and international visitors. It was closed on weekends and public holidays.

Such measures were used to regulate accessibility to the public, deploying bureaucratic measures to hinder rather than help the public. Visitors, for example, needed to apply for admission. There were only ten tickets available for each allotted hour of the day. But three visits were required to secure these allotments: first to apply for access, second to collect the ticket (tickets weren’t available on the same day as attendance), and then finally to attend. This method privileged more affluent and mobile members of the public, and reduced access to lower class members who otherwise worked long hours and were unable to make the necessary appointments (all during regular working hours) in order to gain entrance.

Across early 19th century, however, this slowly changed. First, same day tickets were allowed; gradually the days open to the public were added; and finally, the museum became open to the public on weekends and public holidays. Eventually ticketing was removed altogether, but replaced with names being registered in a log book upon entry. Even so, all visitors were directed by a guide: no free roaming was allowed. Finally, however, time restrictions were lifted and people could wander freely without a guide.

At the end of the first decade of the 19th century, attendance to the British Museum was less than 10,000 visitors per year. By 1840, there were well over half a million visitors per year. With the increased numbers of visitors came an increased concern over touching, which eventually led to rules regarding this, and those ubiquitous signs. But the underlying rationale is counter-intuitive, and instructive.

The prohibition on touching was essentially class-based. Since the French Revolution in the late 18th century – when statues, for example, were toppled – there had been a growing fear in England that museums and galleries could become the target of the rage of the labouring classes. This is why, in the 19th century, museums and galleries used actual police to patrol the spaces (the precursor of our contemporary invigilators). As these were considered public spaces, the police kept order as they would in the streets. Eventually rules were introduced – such that bags and umbrellas were to be kept in cloakroom; people could not touch the art, they could not speak loudly, and they could not eat in the gallery spaces (because of the smell) – all of which were, quite literally, policed.

Not touching the art became a way to elicit and maintain respect and authority for the elite culture which the collections of the day represented. Only after the labouring classes gained entry to these spaces did touch become associated with damage, lack of common sense, and lack of justice. The ‘vulgar touch’ of the labouring classes was seen to ‘profane’ the exhibits (Candlin). However, before, during, and after this increased police presence and enforcement of rules of public order inside museums and galleries, there are indications that these fears were misplaced. Fiona Candlin examined the Annual Select Committee Reports from 1830s through the 1850s and found that ‘all commented on the singularly good behaviour of the working-class visitors, stating that nothing had been damaged or stolen.’ And yet, in the period prior to this, when museum-going was largely an elite pursuit, ‘there were repeated complaints about the damage wrought by English “connoisseurs”.’ Upper-class attendees would continue to touch items with abandon, at times resulting in damage.

This reinforces the notion that these rules against touching were initially class-based, because the actual preservation of the art works, for their own sake, was still not largely a concern. The main concern was maintaining control of the masses. As Candlin states:

since exhibiting collections also exposes them to damage. Light, heat, humidity, dryness, pollution in the atmosphere, attacks by insects and bacteria, and the chemical effects of adjacent materials can all affect objects adversely, whilst transporting objects within and between institutions can place objects at far greater risk than handling them when stationary. Far from exhibitions for the eyes being safe, the museum develops ways of negotiating and compensating for these actual and potential hazards in order to keep them on display.

As in the previous century, such damage was expected and accommodated into the experience of visiting a museum or gallery, especially if those visitors were of the right class.

3.

Into the 19th century, and especially by the latter half of the century, the public museums and galleries were guided by a form of paternalistic, civic humanism, in which it was considered that the labouring classes lacked the time and resources to learn, and so should be helped by the simplifying and edifying organisation of the public museum or gallery. Not touching, not speaking, not eating, in turn, emphasised the importance of sight. Art as visual media, and museums as sites of visual learning, became linked to the maintaining and disseminating of certain forms of elite cultural authority.

In this, curators became the harbingers of approved knowledge, whose role was to transmit certain messages to these otherwise uninformed viewers. Collections became arranged to make that ‘message visible’, centring and directing the eye in the process. Gone is the roaming eye of the cabinet of curiosities, to be replaced with the directed eye of the modern museum. This required, for example, establishing relations between written labels and exhibits – as an index of a more general 19th century shift toward subordinating things to words: ‘…the thing is subordinate to the word, and thereby sight to the direction of a controlling intellect (the curator’s)’ (Bennett). Collections, organised by label, became increasingly arranged into a visual system that allowed an underlying rational system to be revealed. Previously, bureaucratic measures were taken to keep the public out; now it was deployed to keep the public in.

By the late 19th century, this underlying rational system was predicated upon Darwinian evolutionary theory. This required museums to become organised along more linear lines, displaying objects from cultures and peoples that traversed the ‘least’ evolved to ‘most’ evolved; with their present moment being the pinnacle, in which the visitors were encouraged to see themselves reflected. This allowed the lower class subjects to situate themselves in global nature and history (i.e. as members of the British Empire).

In this, museums and galleries were public, open spaces, where people were not only seeing the art, but seeing each other. They were being shaped accordingly as members of a public. The organisation of museums and galleries along lines of civilisational progress – which meant national, racial and religious chauvinism – allowed modern citizens to understand themselves within this context, as the apex (and beneficiary) of this perceived progress. Politically, this was part and parcel of a broader range of public amusements designed to organise the labouring classes into deferential patriots. One such example, in Great Britain, in the late 19th century being the Primrose League, in which members were given honorifics, such as ‘Knights’ and ‘Dames’, as a way to situate themselves within God and Queen and Country.

4.

Throughout all of this was the changing role of the curator. By the late 19th century, the role of curators was to perform everything from opening the doors, lighting the fires, cleaning the gallery spaces and the public restrooms, as well as installing and storing the art, creating labels, organising and arranging the gallery spaces, as well as general administration. In short, everything.

Into the 20th century, this role became more specialised, focusing less on janitorial and administrative duties, and more on what we’d now consider the more narrowly defined ‘curatorial’ aspects of the job. In the 1930s, the role became more professionalised, when in 1933, the first formal qualification was launched, a diploma through the Museums Association. Training included the touch and handling of objects, in the tradition which extended back through 17th and 18th centuries, when private collections were the norm; the aura of which ensured that curators would consider themselves distinct from the general public.

However, institutional changes, educational reforms, and increased class numbers, led to a bifurcation in roles and qualifications of curators. In 1953, a specialty course focusing on the practicalities of collection maintenance, conservation, preservation, and so on, was first introduced; with ‘curatorship’ being once more separated out, and yet again more narrowly defined, becoming less hands on, and more theoretically oriented through instruction in art history, and later art theory, all of which privileged sight and rationality.

But even from the beginning of the professional role in the 1930s, curatorship began functioning within the paradigm of the relatively new disciple of modern art history. Fiona Candlin shows how modern art history formed as a discipline in the early 20th century, circumscribed mainly by the pioneering work of Aloïs Riegel, Bernard Berenson, Heinrich Wölfflin, and Erwin Panofsky; all of whom constructed a framework within which touch was considered ‘primitive’, child-like, non-rational, and pre-modern; with sight being associated with modernity and rationality.

Aloïs Riegel’s Late Roman Art Industry (1901) traced the separation of sight from touch by looking at the development of art during the period from Egyptian (tactile), through Greek (tactile-optical), to Roman times (optical). These sensory characteristics are linked to ‘national character’, and to religion (from Egyptian paganism to Late-Roman Christianity), the movement from each to each marking the progress of civilisation.

Bernard Berenson’s Florentine Painters (1897) suggested a similar progression from touch through to sight, albeit in individual (instead of national) terms: infancy is a time for learning through touch, but maturity is characterised by learning through sight. Berenson separated the ‘cannibal’ senses – touch, taste, and smell – from the higher senses – sight and hearing. This separation was seen in terms of the Western philosophical tradition that separates mind from body, and associates art with transcendence. Touching and profane materiality became associated with non-Western cultures.

Heinrich Wölfflin’s The Principles of Art History (1915) distinguished between the material and the immaterial, with art being concerned with the latter, associated with transcendence. Touch was associated with the ‘childhood of civilisation’ (Candlin). A mature cultural art was associated with appearances only. Lower, material art was associated with an unthinking nation. Interestingly, France was considered such an unthinking nation: Germany was, after all, at war with France at that point, and the boundaries of art history were being drawn according to national chauvinisms and competing empires.

Erwin Panofsky’s Perspective as Symbolic Form (1927) traced the development of perspective in art as being an index for degrees of abstraction and rationality, from lower to higher forms. Candlin:

Panofsky predicated modern empirical knowledge, enlightenment philosophy and the future of science on the shift away from tangible sensory experience towards an abstracted system of visual representation. Touch could only be subjective and limited... From the Renaissance onwards, “the compasses – namely, sound judgement – [were] in one’s eyes and not in one’s hands.” For Panofsky at least, touch was antithetical to modern knowledge and rational thought.

Together, these figures demarcated the field of modern art history, by creating a framework predicated upon the separation of touch from sight. Art became a disembodied visual experience, supported increasingly by history and philosophy in the form of art theory. Modern curators then instrumentalised this history within museums and galleries.

5.

Even when the paradigm of visuality and rationality was contested in the mid- to late-20th century, in both theory and practice, it tended to perpetuate, rather than replace, the division and hierarchy between the senses; and to bring into sharper relief the role of discursive theory over the experience of things; and so ultimately reinforced the old paradigm of sight and rationality, with exceptions only proving the rule.

This is because the dominant paradigm was first constructed by establishing a binary opposition between sight, on the one hand, and the other senses, on the other hand. And then building a hierarchy around this, with sight being privileged over the other senses. This formal structure remains in place even when somebody, for example, replaces isolated sight with isolated touch or smell. The senses are still abstracted and separated out from each other, and one is still given a privileged position over the others. Reversing the order of the content of a hierarchy does little to remove the hierarchy itself.

Further, Candlin argues that the general binary of touching versus not-touching is also reinforced if we simply overturn it completely and suddenly allow unrestricted touching of the art. It doesn’t necessarily add anything to our appreciation of all art and its wholesale application is as unthinking as the wholesale rule against touching art. Candlin uses Duchamp’s Fountain as an example: touching it wouldn’t add anything to the experience of seeing it (moreover, we don’t touch actual urinals when used as urinals). Furthermore, contemporary video art doesn’t require touching at all in order for it to be fully experienced (although it usually requires to be heard as much as watched).

Candlin takes as an example for this tendency a strain of feminist art theory operational in museums from the 1970s that took the dominant paradigm to mean that sight equals privileging the male gaze, and that therefore (or so they surmised) the exclusion of touch equals the exclusion of women. So exhibitions of art works that privilege touch were then created with the assumption that this in some way undermined the dominant (male) paradigm. Candlin argues, however, that this doesn’t undermine the dominant paradigm at all, but is actually consistent with it: it is still predicated on accepting that sight = masculinity and touch = femininity. Moreover, by continuing to allow art theory to direct curatorial thinking in this way omits the more complicated history that touch was actually part of male artisanal culture as much as female domestic culture; it also further excludes female painters and visual artists from inclusion.

6.

Subordinating experience of art to the rationality of certain theories of art – which is an extension and enhancement of the 19th century practice of subordinating things to words, under a new guise – also contradicts other attempts in the late 20th and 21st century to ‘democratise’ galleries and museums, by making them more accessible to the public. The initial contradiction here is that this greater access is offset by the increased assumption that knowledge of art theory and art history is a prerequisite for experiencing the art in the right way. This immediately excludes many intellectually and socially who are also, at the same time, given greater physical access to collections. These social and intellectual barriers still exist, even when physical barriers are removed.

Particularly in the 1990s and beyond, attempts were made to break away from the bureaucratised, organised collection-based museum and gallery, and new spaces were reconfigured as ‘laboratories’, and experiments in inclusivity, of breaking down barriers between institutional and social spaces. This was seen as a move against the hierarchies and exclusivity of sight and rationality; such moves were often accompanied by a discourse of liberation or emancipation, under a veneer of a ‘rhetoric of democracy’ (Bishop).

This is, of course, a misunderstanding of democracy, and assumes that any space that brings many people together is automatically ‘democratic’. It’s not. Mobs, for example, are not democratic, and crowds in a shopping centre or in a sporting arena are not necessarily democratic either. Other conditions are required for such spaces to be considered democratic (for example, discussion and deliberation and power to make decisions).

Moreover, inclusion is always (albeit counterintuitively) defined against exclusion, and so it becomes a question of how aware one is of the levels of exclusion that exist, many of which remain invisible. Each new act of inclusion reconfigures new areas of exclusion (as in the example above: a ‘feminist’ exhibition that privileges touch over sight would exclude women visual artists).

As Candlin (drawing on Bishop, who in turn draws upon the work of Rosalyn Deutsche) argues, initial moves in the 1980s toward inclusivity and access in galleries and museums were accompanied by an economic shift from a goods- and commodity-based economy to a more service-based economy; one in which people sought ‘experiences’ rather than things, and these laboratories of inclusivity and access became marketable spaces, as forms of leisure (tourism) and entertainment. Bishop further argues that such ‘experiences’ became curated, ‘staged’ and ‘scripted’, with the curator maintaining their hierarchical position as stage-manager of such marketable experiences.

The resultant collapse of the barrier between institutional and social space – under the auspices of a marketable space – created ‘microtopias’ (Bishop). The achievement of (consumer) microtopia has replaced the aspiration for (political or social) utopia. Instead of confronting the complexity of long-term, real-world problems, in the service of some future ‘utopia’ (as an ideal only, which it is understood may never be achieved, but must be striven for), such complexity is eschewed for immediate, short-term, personal satisfaction, and withdrawal into a ‘microtopia’; in which participants lose themselves in some curated collective activity, under the shared illusion that it is somehow inclusive and an inversion of the dominant power structures in the larger society (spoiler: it’s not).

The ‘rhetoric of democracy’ in this case is, in reality, a withdrawal from democracy as a working possibility.

7.

One of Marshall McLuhan’s four laws of media is the law of reversal; or the idea that if you push a particular media far enough it will reach a limit-point, beyond which it reverses direction and flips into its opposite.

In one sense the subordination of art objects to art theory may be seen as an example where the visual index of rationality has been reversed and art objects are no longer clearly seen in their own right. They cease to be objects of art and become, first and foremost, illustrations of some particular art theory or philosophy.

But a more practical example of McLuhan’s law of reversal can be seen with the introduction of the internet, and mobile screen devices, especially with photo imaging capabilities. So ubiquitous have these devices become in the early 21st century that it is largely impossible to police their use in galleries and museums; where previously photography wouldn’t be allowed, it is now the norm. This enhances the museum or gallery as a visual space, but it has also reversed into its opposite with art no longer being directly seen or looked at, but only mediated through the lens and screen of a mobile phone that takes digital images of the object – sight itself being deferred, kept for a future time when the image may be ignored or merely glanced at once outside the gallery space.

This has already begun to flip further into its opposite with more and more people taking ‘selfies’ with the art, which literally requires them to turn their backs on art. There has also been an increase in instances when doing so has inadvertently knocked over or damaged the art trying to get a selfie. Such as the case of the Los Angeles gallery in July 2017 when a woman, taking a selfie, reversed into a plinth that had a domino effect, knocking over more than half a dozen plinths, damaging over 200k worth of art.

These images may have another use. In 2018, a fire at Brazil’s Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro destroyed a 200 year collection. In response, curators and others put out a call for everybody who had attended the museum in the past decade, and has taken mobile digital photographs of the exhibits, to submit those images to the museum, so they can create a database of images to effectively reconstruct the exhibits virtually, to replace the otherwise destroyed physical collection. This was to supplement the work already done by Google to develop a virtual tour of the museum.

8.

So the situation we find ourselves in is this: from the elevation of sight in the mid-19th century as a way to minimise the ‘vulgar touch’ of the lower classes, to the rule of no touching in the early 20th century to ensure art is not damaged, to the present moment, when such elevation of sight leads to certain practices – use of mobile screens and digital photography – that directly overlooks, bypasses, and, in the process, may otherwise damage, art. We’ve moved from touching art, to not touching art, to no longer even having art to touch. The situation in Brazil suggests that the apotheosis of sight and rationality is complete. Art itself is no longer required; only images in a rationally organised database – and one that is privately owned by a company.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

Works consulted

Bennett, Tony, “Pedagogic Objects, Clean Eyes, and Popular Instruction: On sensory regimes and museum didactics” Configurations, 6:3, 1998.

Bishop, Claire, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics”, October, vol 110, 2004.

Candlin, Fiona, Art, museums and touch, Manchester University Press, 2010.

Classen, Constance, “Museum Manners: The sensory life of early museums”, Journal of Social History, 40:4, 2007.

Classen, Constance, & Howes, David, “The Museum as Sensescape” Western sensibilities and Indigenous artifacts”, in Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Cultures (ed. Elizabeth Edwards), chapter 7, 2006.

Deutsche, Rosalyn, Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics, MIT Press, 1998

McLuhan, Marshall, Laws of Media: The New Science, University of Toronto Press, 1992

Great piece. Love the story of the selfie-taker and the cascading plinths.

The discussion reminds me of a time I visited a relative who worked in Geology Department of Melb Uni (late 70s-early 80s, can't remember) and they had a piece of moon rock on display. It was "protected" in a class cabinet, but my relative, for some reason, had access to a key and he he opened it and let me hold it in my hand. Changed the experience completely.