14. On the transposition of The Myth of Sisyphus into an argument about language

Or, the influence of Brice Parain’s philosophy of expression on Albert Camus

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: please consider signing up to this newsletter (or updating to a paid subscription).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

1.

In Part Four of The Plague, when Tarrou uses the word ‘plague’ for the first time, within the context of the novel, in its metaphorical sense, to connote ‘abstraction’ – claiming, in that moment, “that everyone carries the plague inside them, because no one, yes, no one in the world is immune” – he suggested also how best to counter its effects: “I understood that all human sorrow came from not keeping language clear. So I chose the side of clear speech and action, to put myself on the right track.” This resolution, of course, contains within it a deeper set of problems pertaining to the very nature of language itself. It is an ambiguity which Camus was fully conscious of, and which he confronted directly.

In late 1943, when Camus first moved to Paris, he was given a paid position as a reader at his publishing house, Gallimard. There he became friends with one of the editors, the writer and intellectual, Brice Parain. Parain had published two books during the 1930s, but in the early 1940s he published another two books which explored the relationship between philosophy and language. It was these last two books, in particular, that caught Camus’ attention.

Parain was a friend of Jean Grenier (Camus’ teacher and mentor in Algeria), from his own days at Gallimard. In March 1942, Grenier informed Camus that Parain had read Camus’ first collection of lyrical essays – The Right Side and the Wrong Side (1937) – and liked it a great deal. In August of that year, Grenier told Camus about Parain’s forthcoming book, Recherches sur la nature et les functions du langage (1943). A month later Camus told Grenier that he had read Parain’s previous book, Essai sur logos platonicien (1941), ‘with great interest’ and found its critical reappraisal on the role of language in philosophy to be ‘necessary’. He looked forward to reading the next volume. Then, in January 1943, when Camus visited Paris briefly, in between pneumothorax treatments, he met Parain for the first time. By the end of that year, having by then read Parain’s new book on language, Camus wrote a long essay on Parain’s ideas, its publication coinciding with Camus moving to Paris more permanently.

2.

What is remarkable about Camus’ essay – “On a Philosophy of Expression by Brice Parain” – is that it is effectively a transposition of his own arguments, presented in The Myth of Sisyphus, also recently published, into an argument about language. ‘For Parain’s basic premise is that if language is meaningless then everything is meaningless, and the world becomes absurd,’ Camus writes. ‘We know only by means of words.’

This premise, however, is only the first of two presented by Parain in his work. This premise – which he refers to as the ‘sensualist hypothesis’ – is countered by a second one – which he calls the ‘idealist hypothesis’. Camus cites Parain’s outline of these: “If man chooses the sensualist hypothesis, he will obtain the external world but lose knowledge; if he chooses the idealist hypothesis, he will obtain knowledge, but will not know how to deal with tangible reality and his knowledge will be useless.” Camus transposes these hypotheses, these basic premises, more succinctly into a choice between ‘absurdity’ or ‘miracles’, respectively. ‘Thus we can name things only with uncertainty, and our words become certain only when they cease to refer to actual things,’ Camus writes: ‘In neither of these cases can we count on words to tell us how to behave. And tragedy begins as a consequence.’

In parsing this choice, Camus introduces the Pascalian wager which he referenced and criticised in The Myth of Sisyphus as the model for philosophical suicide. But in the current context, he finds this wager turning on a question of language. ‘This is the choice Pascal brings back in all its cruelty,’ Camus writes here:

Uncertain of language, trembling before the enormity of falsehood, incapable of making paradox reasonable, Pascal merely convinces himself that it exists. But he denounces this paradox better than anyone else: “Two errors,” he writes. “1. To take everything literally, 2. to take everything spiritually.” Thus Pascal suggests not a solution but a submission: submission to traditional language because it comes to us from God, humility in the face of words in order to find their true inspiration. We have to choose between miracles and absurdity; there is no middle way. We know the choice Pascal made.

In Sisyphus, Camus criticised a number of contemporary – and near-contemporary (Kierkegaard) – existential thinkers for making this leap, in order to escape the absurd. Twelve months later, in his essay on language, Camus uses Parain’s work to expand this charge of philosophical suicide to cover much of the history of Western philosophy, from Plato to Hegel. ‘The history of philosophy always brings the thinker back to the Pascalian dilemma,’ Camus writes. And, for Camus, they all seem to make the leap, in one way or another, in order to retreat from the absurd.

3.

It is at this point that what probably drew Camus to Parain becomes clear. For Parain, in his work on language, like Camus, in his work on the absurd, refuses to make the leap. For Parain, this means keeping the choice in suspense. “Any philosophy which does not refute Pascal is vain,” Camus cites Parain as saying. And yet, as Camus would argue, any ‘philosophy’ that does refute Pascal would cease to be philosophy: it would be literature. Elsewhere in this essay, when Camus cites Parain’s distinction between the sensualist and idealist hypotheses, he includes Parain’s qualification:

“In the first case [the “sensualist hypothesis”], his language will become literature; in the second [the “idealist hypothesis”], the logical system, developed from a few simple propositions, will soon appear as the fruit of a dream, or as the appalling amusement with which a prisoner might occupy his solitude.”

Perhaps this is why, in part, Camus always wrote in the essay form – which is the chosen genre, not just of his lyrical essays, but also his book-length essays, The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel – because this is a literary discourse, and not a philosophical discourse. The essay form is precisely a discourse which, for Camus, resists the pretensions of philosophy, and avoids its constant evasions and self-deceptions. And literature – be it in the form of the theatre, a work of narrative fiction, or an essay – is concerned with recognising the absurd experience, refusing to deny it or to retreat from it, while, at the same time, resisting it. ‘No doctrine tempts it,’ Camus says of art, generally, and literary discourse, in particular. In Sisyphus, this leads to Camus’ central conclusion – that of rebellion – which then structures the literary discourse of his second cycle of works, including The Plague and The Rebel.

On this point, in his essay on Parain, written concurrently with drafting the second version of The Plague manuscript, Camus once more transposes his argument from Sisyphus into an argument regarding language. In Sisyphus, the position of rebellion was to disallow a sense of meaninglessness from descending into despair, to physical or intellectual suicide, or later, in The Rebel, to avoid legitimising political murder and violence. As Camus states, in his essay on Parain:

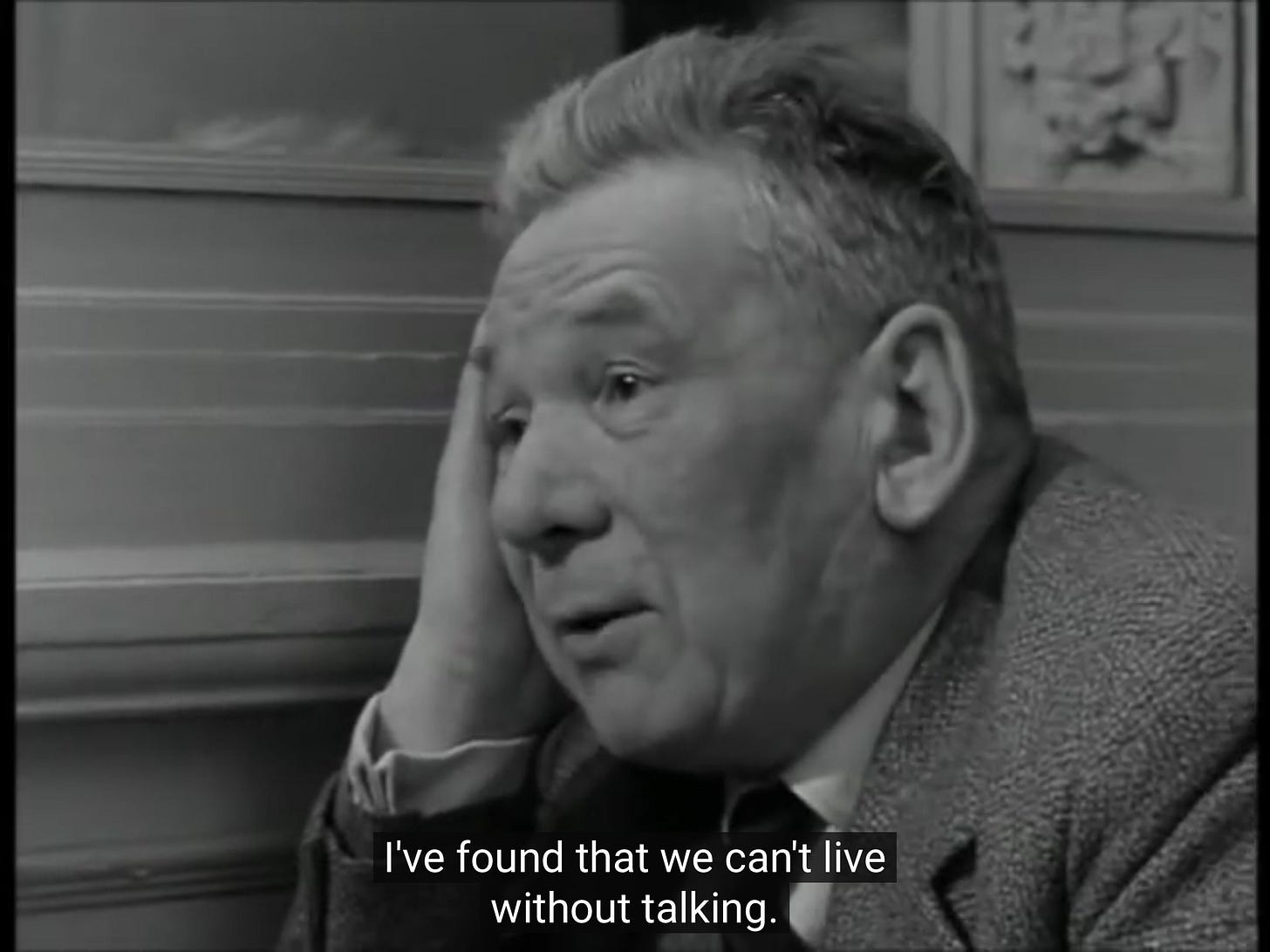

It would indeed be a mistake to imagine that what we have here is an argument which simply concludes that the world is meaningless. Because Parain’s originality, for the time being at any rate, is to keep the dilemma in suspense. He does of course say that if language has no meaning then nothing can have any meaning, and that anything is possible. But his books show, at the same time, that words have just enough meaning to refuse us this final certainty that the ultimate answer is nothingness. Our language is neither true nor false. It is simultaneously useful and dangerous, necessary and pointless. “My words do perhaps distort my ideas, but if I do not reason then my ideas vanish into thin air.” Neither yes nor no, language is merely a machine for creating doubt. (emphasis in original)

This is, of course, also an apt description for the way language is used in literature.

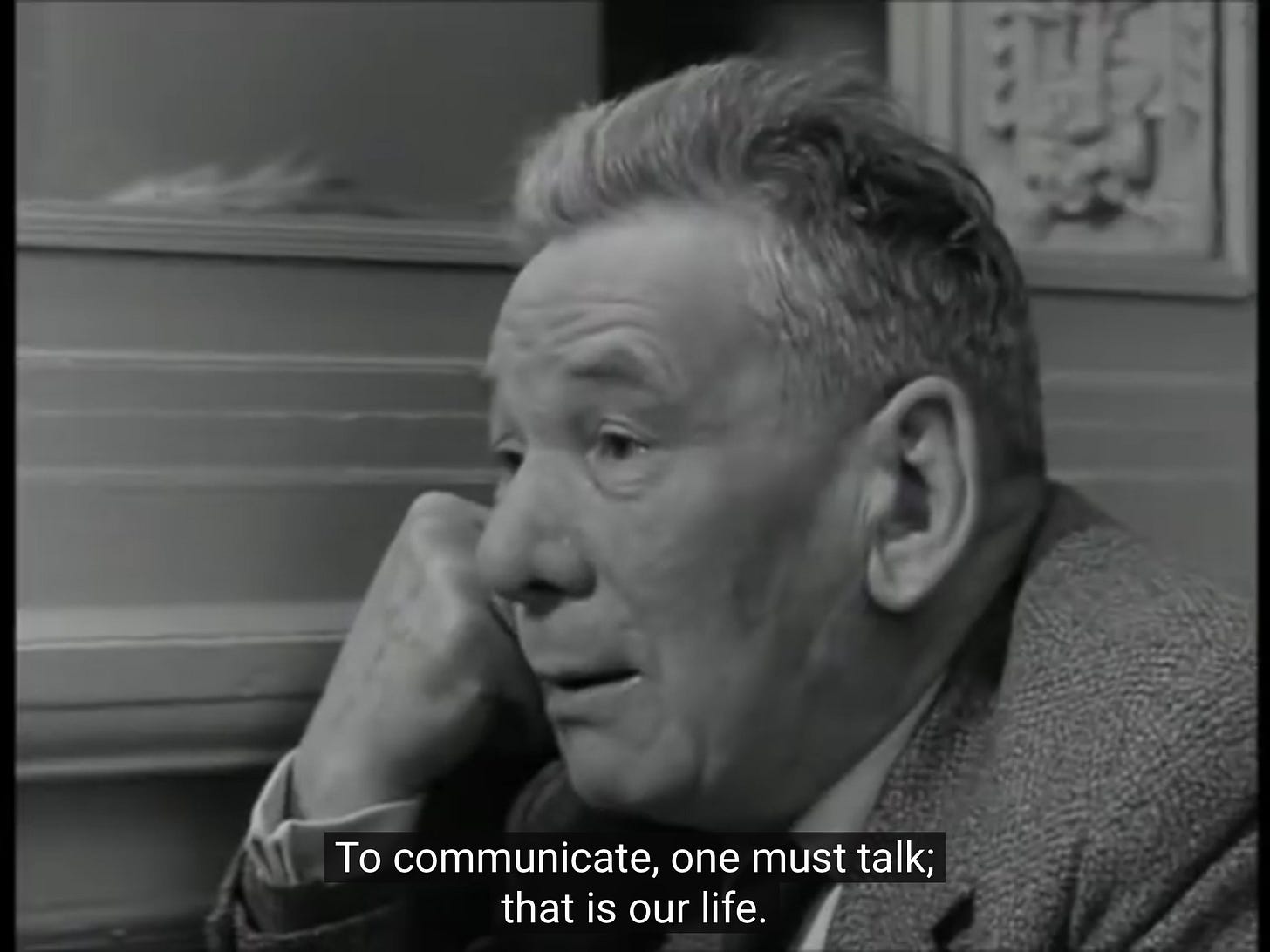

This recalls also Camus’ position in Sisyphus: ‘The absurd has meaning only in so far as it is not agreed to.’ By transposing this position into an argument pertaining to language, Camus suggests that language itself may also be a tool for rebellion. This is why, returning to Tarrou in The Plague, the character argued that not only does “all human sorrow came from not keeping language clear”, but that the solution is also to be found in language, in the resolution to always choose “the side of clear speech and action”. In this way, language may be deployed – as ‘a machine for creating doubt’ – in which this doubt inoculates oneself against the comfort of abstractions and the temptation of false certainty, a tonic against nihilism and ideology.

This position can be found in the conclusion to Camus’ 1943 essay on language, a position which is very much a gloss upon Tarrou’s later statement in The Plague:

Instead of using the uncertainty of language and the world to justify every possible kind of liberty.... men are striving for an inner discipline. The tendency is no longer to deny that language is reasonable or to give free rein to the disorders it contains.... In other words, and this intellectual move is of the highest importance for our time, we no longer use the falsehood and apparent meaninglessness of the world to justify instinctual behavior, but to defend a prejudice in favor of intelligence. It is a question merely of a reasonable intelligence that has returned to concrete things and has a concern for honesty.

4.

That Camus was consciously transposing his arguments from The Myth of Sisyphus – regarding the absurd, philosophical suicide, and rebellion – into an argument about language is corroborated by an essay he wrote in 1950. “The Enigma” was written, in part, to prepare the ground for the publication of The Rebel, which was released the following year, but more so, to refute (yet again) the many misconceptions that had arisen around The Myth of Sisyphus, as well as his novels. While in his 1943 essay on Parain Camus had transposed his arguments from Sisyphus, here in “The Enigma”, he reverses the tactic, and transposes his own interpretation of Parain’s arguments about language into a question of the absurd. He especially emphasises the point he made in that earlier essay that, while still operating within the limits of the sensualist hypothesis, while remaining faithful to the absurd, ‘words have just enough meaning to refuse us this final certainty that the ultimate answer is nothingness.’ And so, in “The Enigma”, Camus writes:

In any case, how can one limit oneself to saying that nothing has meaning and that we must plunge into absolute despair? Without getting to the bottom of things, one can at least mention that just as there is no absolute materialism, since merely to form this word is already to acknowledge something in the world apart from matter, there is likewise no total nihilism. The moment you say that everything is nonsense you express something meaningful. (emphasis added)

In the same essay, he extends this argument to counter also the charge of ‘literature of despair’.

What, in fact, does “literature of despair” mean? Despair is silent. Even silence, moreover, is meaningful if your eyes speak. True despair is the agony of death, the grave or the abyss. If he speaks, if he reasons, above all if he writes, immediately the brother reaches out his hand, the tree is justified, love is born. Literature of despair is a contradiction in terms. (emphasis added)

This is a point – which we have already touched upon in an earlier instalment of this newsletter – that Camus would reiterate the following year in The Rebel: ‘Even if the novel describes only nostalgia, despair, frustration, it still creates a form of salvation. To talk of despair is to conquer it. Despairing literature is a contradiction in terms.’

It is a point Camus had already by then attempted to show in The Plague; but it is an idea we can trace back to his 1943 engagement with the work of Brice Parain.

Read the next installment, where we explore further how Camus’ thinking about language influenced the background to his writing The Plague. HERE.