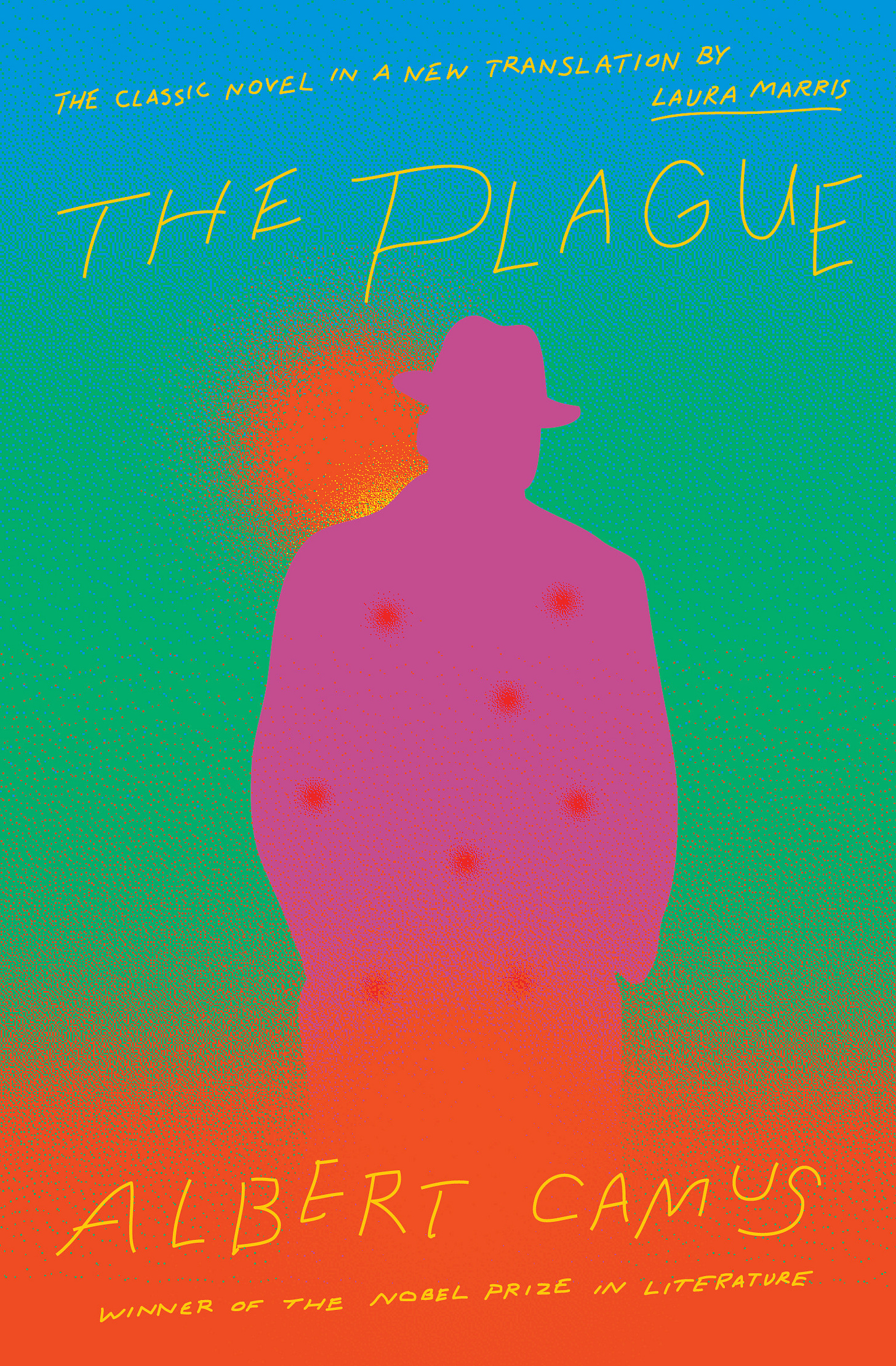

15. On the restoration of communication as a form of rebellion in Albert Camus’ thought

Or, how the play The Misunderstanding (1944) was a rehearsal for The Plague (1947)

1.

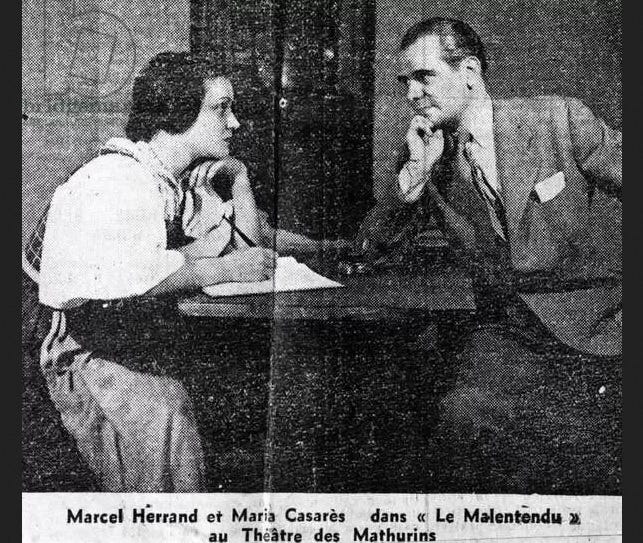

During the early period of the German occupation of France, 1942-1943, while Albert Camus was recovering in Le Panelier from his regular treatments for tuberculosis, and while he was working on the second version of his plague novel, he was also meditating deeply on the language studies of Brice Parain. It was in this context that he wrote a play, The Misunderstanding, which had a brief run in Paris, in the Théâtre des Mathurins, in late August 1944 – incidentally, during the first days of the liberation of Paris. The gloomy tenor of the play ran counter to the spirit of the moment – which is partly why the run wasn’t very successful – although in hindsight, it also proved somewhat prescient, regarding the impending purge and Camus’ own thinking regarding that experience. In many respects, his work on this play, along with the meditations on Parain’s language studies, prepared Camus for this coming period.

Although Camus’ 1943 essay, “On a Philosophy of Expression by Brice Parain”, is his most important and focused statement on the topic of language, it would be a mistake to see this as the starting point for his reflections on language, more generally. His lyrical essays of the late 1930s contain meditations on language that may be seen as rehearsing Camus’ later arguments in Sisyphus, and which therefore prepare his reception for encountering Parain’s works in 1943, and for his transposing of the arguments of Sisyphus into an argument about language.

2.

In his 1937 essay, “Death in the Soul”, Camus describes a trip to Prague. ‘I was thousands of kilometers from home,’ he wrote. ‘I could not understand their language... I felt lost.’

Without cafés and newspapers, it would be difficult to travel. A paper printed in our own language, a place to rub shoulders with others in the evenings enable us to imitate the familiar gestures of the man we were at home, who, seen from a distance, seems so much a stranger. For what gives value to travel is fear. It breaks down a kind of inner structure we have.

Here Camus reflects on how language contributes to creating an ‘inner structure’ which creates the illusion of familiarity within the world, an illusion which is disrupted when the language collapses, or else, as when one travels, the local language is different from one’s own.

Travel robs us of such refuge. Far from our own people, our own language, stripped of all our props, deprived of our masks (one doesn’t know the fare on the streetcars, or anything else), we are completely on the surface of ourselves.

Here Camus begins to outline the experience of the absurd – without yet naming it as such – which he would later explore in Sisyphus.

The curtain of habits, the comfortable loom of words and gestures in which the heart drowses, slowly rises, finally to reveal anxiety’s pallid visage. Man is face to face with himself: I defy him to be happy … And yet this is how travel enlightens him. A great discord occurs between him and the things he sees. (emphasis added)

It is clear from this why Parain himself would have thought a great deal about these essays of Camus’ when he finally read them in 1942.

3.

These meditations on language and the experience of absurdity continued in Camus’ second collection of lyrical essays. In “The Wind at Djemila”, for example, he reflects on how language is often used to console and distract from the present moment. ‘What meaning do words like future, improvement, good job have here? What is meant by the heart’s progress?’ he writes. ‘If I obstinately refuse all the “later on’s” of this world, it is because I have no desire to give up my present wealth.’

What is interesting about these moments when Camus reflects on language is that, more often than not, they are also moments where he explicitly makes a link between how we use words and how we directly think and act – that consistent thread, which runs through his work, and which we have already cited previously, regarding the necessity of thinking and acting without the mediating prop or support of abstract systems, doctrines, or ideologies, which proffer false promises of alleviating from each individual the responsibility for their own lives.

It is in the same paragraph, already cited above, from “The Wind at Djemila”, where he first stated: ‘Everything I am offered seeks to deliver man from the weight of his own life.’ But here we can see that Camus explicitly links this situation to a question of language. To refuse this offer amounts to finding the right word: ‘But it seems to me that if I had to speak of it, I would find the right word here between horror and silence to express the conscious certainty of a death without hope.’ Likewise, it was in the context of his later essay on Parain where Camus stated:

What we can learn from the experience Parain sets forth is to turn our back upon attitudes and oratory in order to bear scrupulously the weight of our own daily life. “Preserve man in his perseverance,” we read in Essai sur la misère humaine, “it is through this that he becomes immense, and gains the only immensity that he can transmit.”

It is in this context, and following this consistent thread that runs through Camus’ life and work, that we can see how this essay on Parain not only transposes arguments from Sisyphus, but at the same time prepared the ground for Camus’ arguments to come. It is in Parain’s work, for example, where Camus finds a criticism of 19th century German philosophy and Hegel in particular. This criticism is based on ‘the compromise’ with the ‘Pascalian dilemma’, which Camus referred to in Sisyphus as ‘philosophical suicide’. Here Camus reads Parain as arguing that these attempts at ‘deifying history’ operate through smuggling what Parain referred to as the idealist hypothesis into the sensualist hypothesis, which is only possible, Camus states, ‘if we carry our abstractions right into the heart of concrete things.’ And because, for Camus, the sensualist hypothesis is predicated upon the human body and the natural world, it is perhaps no coincidence that it was only within the year of writing this essay on Parain that Camus began including references to Hegel in his notebooks – already cited – which explicitly draw this distinction between history and nature.

4.

When in The Plague Tarrou outlined his resolution to choose “the side of clear speech and action” – to find the tools for rebellion within language – he acknowledges at the same time that language itself is also the source of many of our problems: “I understood that all human sorrow came from not keeping language clear.” It is an idea that can be traced back to Camus’ engagement with Parain. Following his essay on Parain, Camus began expanding his reflections on language to incorporate also its use in communication more generally, associating it with the process of abstraction. Around that time, for example, he wrote in his notebooks:

Communication. A hindrance for man because he cannot go beyond the circle of people he knows. Beyond, he makes an abstraction of them. Man must live in the circle of flesh.

In the second instalment of “Letters to a German Friend”, written in December 1943, Camus writes: ‘You always distrusted words. So did I, but I used to distrust myself even more.’ And in the third letter, from April the following year, he writes, describing one of the underlying reasons for the descent into war: ‘It is merely that we didn’t give the same meaning to the same words; we no longer speak the same language.’

Later, around the time that Camus signed the petition to commute the death sentence of Robert Brasillach, he added to his notebooks: ‘I am not made for politics because I am incapable of wanting or accepting the death of the adversary.’ It was in combining these two parts of his thinking – communication and his opposition to the death sentence – that shaped his thinking over the coming years, and which came to structure The Plague.

The first statement of this new way of thinking came in his 1946 lecture, “The Human Crisis”. ‘We must call things by their right names and realize that we kill millions of men each time we permit ourselves to think certain thoughts,’ he said in that lecture. ‘One does not reason badly because one is a murderer. One is a murderer if one reasons badly. It is thus that one can be a murderer without having actually killed anyone.’ Characteristic of this is the process of abstraction which leads to what Camus calls in this lecture the ‘substitution of the political for the living man’, a form of nihilism which tends not to human life, but to the preservation of an ideology in the form of some human caricature. ‘What counts now is not whether or not one respects a mother or spares her from suffering,’ Camus states, ‘what counts now is whether or not one has helped a doctrine to triumph.’

At the heart of all of this is the question of communication, and its disruption:

For this communication of men with one another, in the mutual recognition of their dignity was the truth, then it was this communication itself which was the value to be supported.

And for this communication to endure men must be free, since master and slave have nothing in common, and since one cannot speak to or communicate with a slave. Yes, bondage is a silence, and the most terrible of all.

And to make communication lasting we must eliminate injustice. For there is no contact between the oppressed and the one who profits by oppression – envy also is of the realm of silence.

And to make communication lasting we must proscribe violence and the lie, for the man who lies shuts himself from others, and he who tortures and constrains imposes irremediable silence.

One purpose of rebellion, then, for Camus, becomes the restoration of communication, through the elimination of injustice, slavery, oppression, and violence. Or rather, the elimination of injustice, slavery, oppression, and violence, through restoring our communication – through the rescue and rehabilitation of language from ideology – becomes one of the main tactics of rebellion. ‘For he cannot communicate with his fellows in terms of values common to them all,’ Camus states here of the ideologue. ‘And since he is no longer protected by a respect for man based on the values of man, the only alternative henceforth open to him is to be the victim or the executioner.’ Later that same year, Camus wrote a series of articles for Combat with that title – “Neither Victims Nor Executioners” – arguing against both these alternatives, and arguing instead for a position in which neither one nor the other would be viable.

In both lecture and subsequent articles, the problem of restoring communication revolves around a question of persuasion. In “The Human Crisis”:

This crisis is based also on the impossibility of persuasion. Men live and can only live by retaining the idea that they have something in common, a starting point to which they can always return. One always imagines that if one speaks to a man humanly his reactions will be human in character. But we have discovered this: there are men one cannot persuade.

And later, in “Neither Victims Nor Executioners”, Camus argued, more succinctly, that ‘there is no way of persuading an abstraction’ – and yet ‘we live in a world of abstractions, a world of bureaucracy and machinery, of absolute ideas and of messianism without subtlety.’ This is why, in part, Camus didn’t want to write “Neither Victims Nor Executioners”, knowing already what the reaction would be among his contemporaries, especially the intellectual class, embedded, as they were, inside their own abstractions, cushioned from reality, even as they sought to dominate it. ‘My anguish at the idea of doing those articles for Combat,’ he confided to his notebooks.

Significantly, considering Camus’ ecological imagination, this note is couched in his preference for the concrete of nature over the abstractions of the political. The prior note reads: ‘There are moments when I don’t believe I can endure the contradictions any longer. When the sky is cold and nothing supports us in nature… Ah! Better to die perhaps.’ And then, the very next note, referencing the “Neither Victims Nor Executioners” articles, Camus refers back to this previous note, and ends with what he would prefer to be writing instead:

Continuation of the preceding. My anguish at the idea of doing those articles for Combat.

An essay on the feeling for nature – and sensual pleasure.

5.

The flipside of this question of persuasion, for Camus, was the more difficult question of polemics. Shortly after the publication of The Plague, he wrote in his notebooks:

Polemics – as an element of abstraction. Every time you have decided to consider a man an enemy, you make him abstract. You set him at a distance; you don’t want to know that he has a hearty laugh. He has become a silhouette. (emphasis in original)

The restoration of communication, however, becomes even more complicated when one’s political opponents have rendered themselves abstract, a self-caricature of whatever ideology they are choosing to hide behind, be it on the right or the left. It is this question which Camus would later examine in The Rebel. ‘Language destroyed by irrational negation becomes lost in verbal delirium,’ he writes there: ‘subject to determinist ideology, it is summed up in the slogan.’

In The Rebel Camus repeats the claim – first floated in “The Human Crisis” – that true dialogue cannot exist between a master and slave, a victim and executioner, but that this can be corrected through the process of rebellion, in both thought and action. ‘The mutual understanding and communication discovered by rebellion can survive only in the free exchange of conversation,’ Camus states. ‘Every ambiguity, every misunderstanding, leads to death; clear language and simple words are the only salvation from this death.’

A person who lies cuts themself off from other people, and, as in acts of murder or violence, this reduces the world to silence. For Camus, such violence – whether it is verbal or physical – signifies a ‘rupture in communication.’ And if communication and persuasion is only possible among equals, predicated upon a shared reality, then persuasion must be based on drawing attention to what is always held in common: the physical world, of nature and bodies. ‘Dialogue and personal relations have been replaced by propaganda or polemic, which are two kinds of monologue,’ he states. ‘Abstraction, which belongs to the world of power and calculation, has replaced the real passions, which are in the domain of the flesh and of the irrational.’

He later explains this further, by drawing on an analogy from the theatre, the kingdom of the body: ‘On the stage, as in reality, the monologue precedes death.’

6.

And it was for the stage that Camus first wrote a work which was explicitly composed around these questions of language, communication, and violence. The Misunderstanding was written during the period 1942-1943 when Camus was recovering in Le Panelier, when he was meditating deeply on the work of Parain, and also drafting the early versions of The Plague. The basic plot for this play actually comes from a newspaper article which Camus read in January 1935, in L’Écho d’Alger, regarding a murder in Yugoslavia. Camus first used a variation of this story – transposing the action to Czechoslovakia – in The Stranger. In prison, Meursault finds a newspaper clipping, which he rereads obsessively.

A man had left a Czech village to seek his fortune. Twenty-five years later, and now rich, he had returned with a wife and a child. His mother was running a hotel with his sister in the village where he’d been born. In order to surprise them, he had left his wife and child at another hotel and gone to see his mother, who didn’t recognize him when he walked in. As a joke he’d had the idea of taking a room. He had shown off his money. During the night his mother and his sister had beaten him to death with a hammer in order to rob him and had thrown his body in the river. The next morning the wife had come to the hotel and, without knowing it, gave away the traveler’s identity. The mother hanged herself. The sister threw herself down a well. I must have read that story a thousand times.

For The Misunderstanding, Camus makes more changes to the story – to minimise the number of characters, to tighten the plot, and increase the tension, to make more suspenseful for the stage. Motivations change, too. In The Stranger version, the son keeps his identity hidden ‘[a]s a joke’. But in The Misunderstanding, this story becomes a tragedy of communication and language.

When the son (Jan) first comes to the hotel, he is looked at, but not seen, not recognised, by his mother. This initially throws him. ‘You know quite well it needn’t have been difficult,’ his wife (Maria) says soon after, ‘you had only to speak. On such occasions one says “It’s I,” and then it’s all plain sailing.’ But he decides to return, to take advantage of this cloak of anonymity, to get to know his family and their situation more clearly, before revealing himself.

JAN: ... I shall take this opportunity of seeing them from the outside. Then I’ll have a better notion of what to do to make them happy. Afterwards, I’ll find some way of getting them to recognize me. It’s just a matter of choosing one’s words.

MARIA: No, there’s only one way, and it’s to do what any ordinary mortal would do—to say “It’s I,” and to let one’s heart speak for itself.

JAN: The heart isn’t so simple as all that.

MARIA: But it uses simple words.

Much of the play is then concerned with enacting various aspects of language, the etiquette of conversations, social roles versus private expression, and even bureaucratic aspects of communication: police forms, passports, and identity papers.

THE MOTHER [to MARTHA]: Have you filled in the form?

MARTHA: Yes, I’ve done that.

THE MOTHER: May I have a look? You must excuse me, sir, but the police here are very strict.… Yes, I see my daughter’s not put down whether you’ve come here on business, or for reasons of health, or as a tourist.

JAN: Well, let’s say as a tourist.

In the end, it was his passport – which his sister (Martha) had an opportunity to see at the beginning, but didn’t take – which revealed his identity to his family. But they had already killed him by then. Afterwards, when his wife returns, his sister explains what happened. And once more, the situation is described in terms of a problem with communication and language.

MARTHA: Again, you are using language I cannot understand. Words like love and joy and grief are meaningless to me.

MARIA [making a great effort to speak calmly]: Listen, Martha—that’s your name, isn’t it? Let’s stop this game, if game it is, of cross purposes. Let’s have done with useless words. Tell me quite clearly what I want to know quite clearly, before I let myself break down.

MARTHA: Surely I made it clear enough. We did to your husband last night what we had done to other travelers before; we killed him and took his money.

MARIA: So his mother and sister were criminals?

MARTHA: Yes. But that’s their business, and no one else’s.

MARIA [still controlling herself with an effort]: Had you learned he was your brother when you did it?

MARTHA: If you must know, there was a misunderstanding.

In a 1957 preface to the publication of his collected plays, Camus discussed The Misunderstanding:

For, after all, it amounts to saying that everything would have been different if the son had said: “It is I; here is my name.” It amounts to saying that in an unjust or indifferent world man can save himself, and save others, by practicing the most basic sincerity and pronouncing the most appropriate word.

It is this idea which, structuring The Misunderstanding in 1943, was developed further by Camus in The Plague.

Next week we will examine how these ideas about language and communication came to structure The Plague.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: please consider signing up to this newsletter (or updating to a paid subscription).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more subscribers, to ensure that it continues.