'Being shown the instruments of torture'

Or, the art and craft of biography

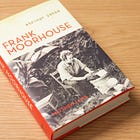

I recently wrote a piece for the Australian Book Review, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Copyright Agency Ltd, a not-for-profit that, among other things, collects licensing fees for reusing copyright materials, which it then distributes to copyright holders. The piece was about the background to a famous court case in the 1970s when Frank Moorhouse successfully sued a university for supplying the photocopy machines that allowed staff and students to copy his work. The ABR also made me record a podcast version of the essay, which I read while suffering a severe flu. It only took about 100 takes and several hot toddies to complete. You can marvel at the final product below.

I also recently did an interview for a members-only newsletter for the Biographers International Organisation, which is an international organisation for, well, biographers... Here’s an edited version of what was said.

What is your current project and at what stage is it?

Last November, I had published the first in a projected two-volume biography of Australian author and intellectual Frank Moorhouse (1938–2022). I’m currently working on the second volume. Moorhouse is best known for a trilogy of fiction books following a character named Edith Berry Campbell through the rise and fall of the League of Nations, finally resettling back in Australia to assist in establishing the nation’s capital in Canberra. But he has written many collections of short stories, starting in 1969. He developed his own form—the “discontinuous narrative”—that links all of his stories together. In total, his body of work is the most sustained imaginative feat in Australian literary history.

But at the same time, Australia has always had troubled literary culture, subordinated by a colonial deference to Britain, but also operating under an inadequate copyright system and a censorship regime that until the 1970s ranked among the worst in the world (not because it was particularly authoritarian, but because it was logistically easier for an island nation with few points of entry and a customs office with extensive search, seize, and destroy powers, to exercise its conservatism more effectively than most).

More so than in other Western countries, in Australia authors need to create the conditions within which they can write; they can’t just write. Many authors of Frank Moorhouse’s generation left because of these conditions (including Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes), but Moorhouse remained and was part of a generation that pushed back against these restrictions, overturned the censorship regime, and through a series of court cases established a copyright system that began to support rather than hinder a local writing culture. All while writing his own books. At the same time, he also led a complicated personal life, where his bisexuality and cross-dressing were often at odds with the conservative conventions of his own family and the nation at large.

Who is your favorite biographer or what is your favorite biography?

I consider myself a reader, first and foremost, and only a writer by accident. The first great reading experience I had was facilitated by Deirdre Bair’s biography Samuel Beckett (1978). I read her book alongside the complete works of Beckett, in a chronological torsion: when I reached the chapter in Bair’s biography when, for example, in 1938, Murphy is published, I put down Bair’s book and started reading Beckett’s Murphy, before picking up Bair again, and so on. This reading practice has since become my norm. The high point was reading Joseph Frank’s multivolume biography of Dostoevsky in unison with Dostoevsky’s complete works.

I have also approached writing my own literary biography, as a reader. I’ve intentionally written Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths (2023) so that if the reader goes back and reads (or rereads) Moorhouse’s own books, they will be justly rewarded; their reading experience enhanced—but without being dogmatically directed.

At the same time, writing biography has forced me to consider more about the craft of the genre. So, I’ve turned to the work of Robert Caro. He really is the gold standard in biography. Reading his works on Moses and Johnson, as well as his reflections on biography itself, has allowed me to be unapologetic in my ambitions and critically honest in how and where I have fallen short.

What have been your most satisfying moments as a biographer?

Biography is very much a group activity, even if we sometimes don’t feel as if it is. It is often a collaboration with people we never even meet. I am not referring only to the subjects we write about and the individuals in their lives who become part of the stories we are writing—although that is also part of it. I am referring more to the people who have created the conditions and the materials that we use, in order to be about to tell these stories. The archivists, for example, who in the 1970s first started collecting material from Frank Moorhouse, so that when I began working on this project in 2015, it was with a sense that I was not starting something new, but continuing something that had begun long before I arrived on the scene. It is also the generosity of other researchers working in adjacent fields—several researchers, for example, who had written about subjects adjacent to Frank Moorhouse, graciously turned over recorded interviews and transcripts and materials otherwise not included in institutional archives. A library assistant in a high school library, for example, went above and beyond to unearth material from the 1950s (when Moorhouse went to that same school), including the earliest extant copy of a short story he had published in a student newsletter.

All these moments of discovery, and rediscovery—the most satisfying moments in the process—were because of the collaboration—knowingly, unknowingly, personally, or indirectly—with other people.

What have been your most frustrating moments?

The most frustrating moments have been when I lacked the resources to exhaust particular research lines of inquiry, especially those that required travel or doing long-term interviews (building rapport and returning time and again to the same subjects).

Compared to other Western nations, Australia is small, in terms of population, but with high illiteracy and an increasing de-literacy among the mainstream, which means it has a very small reading public—even smaller for books about the people who write the books that fewer people are reading. . . . As a result, there are also frustrations regarding the publishing process, where otherwise ambitious projects are scaled down to fit the low expectations of the local market. Frank Moorhouse was critically acclaimed, but he constantly struggled financially, constantly struggled against the conditions of publishing. But there are diminishing returns in writing a book about a man who never made any money writing his own books.

This is all partly the aftereffect of the long period of censorship and inadequate copyright support in Australia, among the lack of other infrastructure and personal dispositions required to facilitate a literary culture. As Moorhouse researched, struggled against, and instituted corrections to this culture of neglect, this meant that I had to research that same culture, to cover much of the same terrain, in order to put his life and work into the broader context of Australian literary, legislative, and publishing history.

But the frustrations of that history were compounded when I had to personally enter into the same circumstances in order to get this book published. I would research and write about some obstacle that Frank faced in the 1960s, and again in the 1970s, and again in the 1980s—and then I would find myself confronting that same obstacle in my own experience.

The whole process was like being shown the instruments of torture before actually undergoing the torture myself.

One research/marketing/attitudinal tip to share?

For me, biography is itself a literary form. Writing biography is an act of imagination, first and foremost; just as reading it requires the engagement of the reader’s imagination, to activate rather than impose upon their judgement. It is precisely because of this that biography writing is so dependent on accuracy, precision, context, and a critical fidelity to the archive—as this is the only material we have available to us in order to select and arrange in a narrative form, in order to build up a moving, developing image of a particular life. Each biography is making an argument, in order to persuade the reader to consider the subject from a particular perspective. And as much as possible that perspective should be consistent with and proportionate to that underlying material, and the life as lived. But it is not absolute and can never be exhausted. It is for this reason that a biography can never be definitive, but is always discontinuous, always open to retelling and reinterpretation. This is what should keep us coming back, again and again, to reading and rereading Moorhouse’s books, and to keep open the question of his life and work. I’ve tried to incorporate that openness and discontinuity into this book.

What genre, besides biography, do you read for pleasure and who are some of your favorite writers?

As a literary biographer, it should not be a surprise that literary fiction is what I tend to read for pleasure. Currently, my favourite Australian writer is Jennifer Mills. Her work—such as her last two novels, Dyschronia (2018) and The Airways (2021)—humble and confound me. But my main area of concern is democracy; actual democracy, as both an idea and a practice and not the counterfeit we are daily offered. What is wonderful about this topic is that researching it requires engaging with a wide range of genres, both fiction and nonfiction, especially history, sociology, and political theory. I’m particularly interested in the African American intellectual tradition as it relates to the question of democracy. The work of Eddie Glaude Jr. is a touchstone for me. That said, I have just finished reading an astonishing new book, The Darkened Light of Faith: Race, Democracy, and Freedom in African American Political Thought (2023) by Melvin L. Rogers; it has kept me pacing my floor for days when I should otherwise be back at my desk working on the second volume of my Frank Moorhouse biography. . . .

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter as it will allow me to write this newsletter more frequently).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

You can find where to buy the book here