It Speaks: Biographers in Conversation

A Conversation on Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths

1.

Earlier this year I recorded a podcast with Gabriella Kelly-Davies discussing the art of biography. The podcast, Biographers in Conversation, explores elements of narrative strategy such as structure, use of fiction techniques, facts and truth, beginnings and endings and to what extent the writer interpreted the evidence rather than providing clues and leaving it to readers to do the interpreting themselves. Kelly-Davies asks biographers how they researched their books; how they balanced a subject’s public, personal and inner lives; and ethical issues such as privacy and revealing secrets.

You can listen to my episode below (or at link above), regarding the book, Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths:

2.

In closing, Kelly-Davies asked me, what is the role of a biographer?

You can listen to me ramble on the podcast, but the edited (and expanded) version is that one of the things I have come to see through this process is that biography is a form of history, but on a human scale. It looks at the history of a nation at large – such as Australia – but from the perspective of an individual within that context.

In this, biography does two things simultaneously: that broader context helps us understand the individual, but the individual’s experiences and interactions helps us understand that broader context, and in more intimate ways than if we were simply to read or write a large scale, conventional work of history.

In part, this is why I refer to Frank’s book as a cultural biography.

Biography also helps us to come to a greater understanding of particular individuals – a more rounded understanding, by considering such individuals in their private, social and public aspects – and through that, we can come to a better understanding of ourselves.

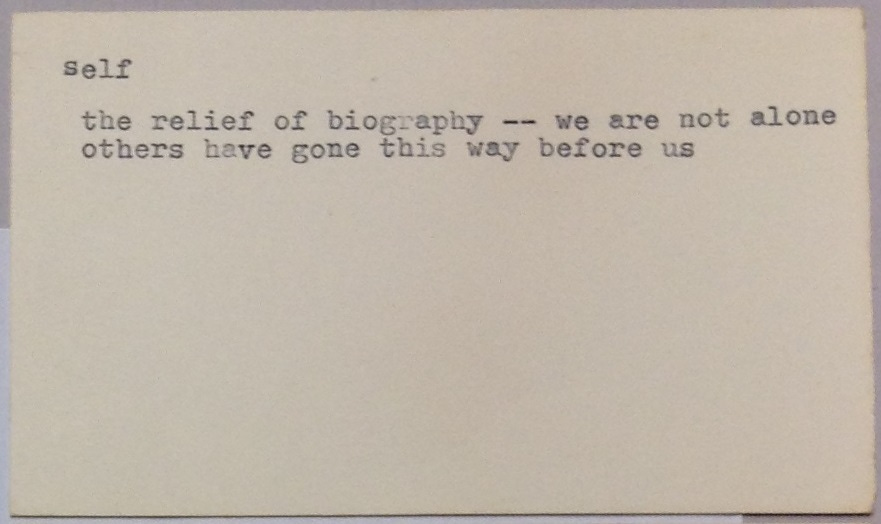

Frank also thought about biography in this way. The epigraph to the book comes from an undated index card from Frank’s archive, where he notes: ‘the relief of biography – we are not alone [/] others have gone this way before us.’

Frank read a lot of biographies in order to situate himself, to come to an understanding of himself. He saw the lives of others as exemplary. He also hoped that his own life, and his own writing, would be exemplary to others coming up after him. He wanted other generations to be able to learn from him, learn from his mistakes, and also learn from what he did well. He wanted to help cut a path that others could follow more easily, in both life and literature.

This is, of course, what the subtitle for his biography – strange paths – refers to a short story – “The Third Story of Nature” – from his first book, Futility and other animals (1969), in which a pregnant woman contemplates her own upbringing, and what she wishes for her unborn child:

But her daughter would be freer. Her daughter would be offered more alternatives with less censure. The following of strange paths would be easier for her and she would have a mother who – if she had not gone far along the strange paths – at least understood why some people did. Or did she understand? What was so great about non-conformity? What was great about independence? What was so good about strange paths? Perhaps her daughter wanted a familiar path? But whatever, her daughter would not have to live with the emotionally gruelling voice which said, ‘Do you really think you are doing a wise thing?’ whenever she deviated from the normal.

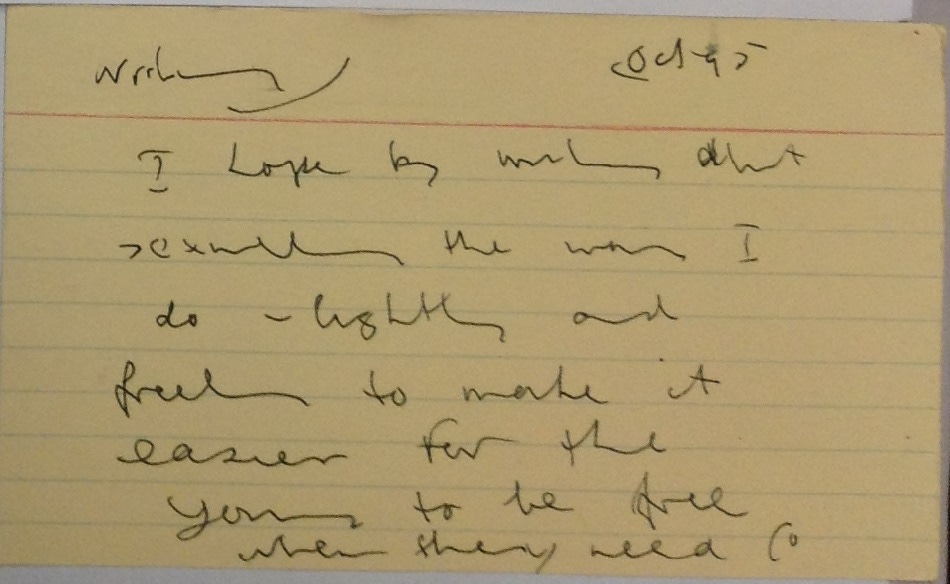

In Frank’s own life, these strange paths referred to many things, especially his fraught sexuality. And these wishes for the next generation – using himself as an example and a cautionary tale – are a refrain in Frank’s personal notes. For example, from 1995: ‘I hope by writing about sexuality the way I do – lightly and freely [–] to make it easier for the young to be free when they need and without anxiety & guilt about what they find they are’

3.

Another role for biography I discuss – particularly because I’m more interested in literary biography and literature generally – comes from an idea Northrop Frye had regarding what he once called ‘a preceptor’ – which is a teacher or a mentor that guides you. In terms of literature, the idea is that readers may have a particular individual author who can lead them into the whole world of literature. So for Northrop Frye, his preceptor was William Blake, the subject of his first book, A Fearful Symmetry (1947). But then, regarding his second book, which he became famous for, The Anatomy of Criticism (1957), he said that he could only have written it through his earlier reading of William Blake. It doesn’t mean he collapsed or reduced all of literature to Blake. He was, instead, using Blake to open up the whole world of literature to him.

And so, as readers, we can also have preceptors. And Frank Moorhouse is certainly for me a preceptor into Australian literature and our culture more generally. Through reading him, I argue, we can get a handle on all of Australian literature and all of Australian culture. And yet, other people may have other preceptors; they may have, for example, Christina Stead. And then, when we have a conversation about Moorhouse and Stead, we’re actually talking about all of literature. It is not just about the individual figures. It is about using this or that figure as a starting point to go off into all these different directions; to find a point of entry into something that we will never entirely be able to fathom or map out.

4.

One point I omitted in the conversation with Gabriella Kelly-Davies was something that I argued elsewhere in an article I wrote for the Sydney Morning Herald in relation to AI and copyright – and that is that literary biography reminds us that literature is written by humans, and what we lose when we hand over or outsource our thinking and creativity to machines.

You can read the article here:

But the main point is in the final paragraph:

I envisage literary biography taking a greater role in the future, as a record and account of the all-too-human struggles and triumphs that go into creating works of literature: a testimony to the value of literary effort, and a culture that, following Moorhouse’s example, works alongside technology when we need to, overcomes it where we can, and resists it when we must.

In the visual art world there are individuals who authenticate works of art, who research and determine the provenance of particular works of art, as part of the biography of individual artists and particular historical cultural milieus. I would argue that with the imminent threat of AI, literary biographers will form part of a necessary coterie – along with scholars, archivists, and critics – who will take on a similar role in the literary field, to authenticate particular works, to trace the provenance of an author’s works throughout their life, and to remind us that the value of literature is precisely its integral role in who we are as humans.

Your gadgets can only distract you from that warrant.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter as it will allow me to write this newsletter more frequently).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

You can find where to buy the book here