1.

A popular misconception is that pessimism is merely a psychological disposition (depression), an existential attitude (despair), or an apolitical stance (resignation). It is construed as petty nay-saying, as unnecessarily negative, with no positive program or thought involved. But as Joshua Foa Dienstag argues, in his book, Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit (2006), such (mis)characterisations are often used to foreclose any deeper inquiry, to dismiss before even seriously considering the position of the supposed pessimist. In taking seriously such positions, however, he has done much to dislodge these popular misconceptions, and revealed an otherwise marginalised tradition of intellectual and political thought that is not just positive in its outlook – and often more clear-sighted than its optimistic counterparts – but which is distinctly ethical in nature.

Dienstag traces the origins of the modern form of pessimism to the crisis of late medieval/early modern period, when the temporal structure of human consciousness shifted from being considered circular to being linear in its constitution. Out of this was born the idea of progress, which very quickly became conjoined with this underlying sense of linearity. So far, all this is broadly agreed upon by cultural historians. But from this, Dienstag raises two points.

The first is that pessimism also finds its origin in this historical shift in time-consciousness; that it also operates within the horizon of linearity. ‘Pessimism too is one of its progeny,’ Dienstag states, ‘the hidden twin (or perhaps the doppelgänger) of progress in modern political thought. What is surprising in standard intellectual histories is how rapidly the idea of linearity is assimilated to the idea of progress, as if progress and stasis were the only two choices available to human thought and the first is straightforwardly the result of linear time while the latter is the direct issue of cyclicality.’

This overturns of one of the popular misconceptions of pessimism: the idea that, in opposing progress, the pessimist wants to go back to a pre-linear, or circular temporal structure, as if to return to some mythical past. Pessimism, on the contrary, is aware that such a move is impossible, because it is preconditioned to operate within such linearity – albeit outside of progress.

The second point is that pessimism has been actively marginalised by the advocates of progress and optimism. ‘From this perspective,’ Dienstag states, ‘the great divide in modern political theory is not between the English-speaking and the Continental schools, but between an optimism that has had representatives in both of these camps and a pessimism whose very existence those representatives have sought to suppress.’

This leads to overturning another popular misconception of pessimism: the idea that, in opposing progress, it is concerned, instead, with promoting a theory of declension. As Dienstag states:

One point that deserves emphasis here is the non-equation of pessimism with theories of decline. While pessimists may posit a decline, it is the denial of progress, not an insistence on some eventual doom, that marks out modern pessimism. Pessimism, to put it precisely, is the negation, and not the opposite, of theories of progress.

From these two starting points, Dienstag marks out the territory of his own study: ‘But as the idea of progress becomes more questionable to us, we have greater reason to turn to the unappreciated history of pessimism. If we find it impossible to return to a circular or cyclical view of the past, and if narratives of progress seem equally mythical, then we ought to reflect more on the nonprogressive, linear accounts of time that remain – and this means pessimism.’

2.

In an earlier work, Dancing in Chains: Narrative and memory in political theory (1997), Dienstag prepared the ground for his later work on pessimism. He did so through examining the relationship between narrative and historical discourse, albeit within the field of political theory, by demonstrating how narrative-time became the horizon within which individuality began to emerge.

Here he distinguishes between reconciliation and redemption as incompatible individual attitudes this emergence of linear time and its associated narrative view of history.

Reconciliation occurs when an individual identifies too closely with this horizon of narrative-time. ‘Reconciliation,’ Dienstag states, ‘is an act of imagination that discourages further imagination.’ While redemption is concerned with accepting an ‘unreconciled existence, one with loose ends and sharp edges.’ This involves an attitude that consciously, and actively, differentiates from within this horizon of narrative-time.

It is this of a redemptive attitude that Dienstag later developed into his understanding of the pessimism. But he does so via reading Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605), alongside Nietzsche. For Dienstag, Nietzsche’s “Dionysian Pessimism” is designed to stimulate action, rather than resignation; it is to undergo a “voluntary quest” (freiwilliges Aufsuchen). ‘It must be voluntary in the strongest sense,’ Dienstag states, ‘because the option of resignation cannot be rationally foreclosed. Nor can the quest be fully motivated by its object since to choose a quest for the questionable is to choose a path to the future that is unknown, but known to be something different from where one sets out. It is an exploration that is bound to be frightening, but holds the potential to be liberating.’

Dienstag argues that it is as an example of this ‘quest-for-no-object’ that Nietzsche finds most appealing about Cervantes’ Don Quixote:

The lack of object throws into relief the idea of pessimism issuing not in a fixed judgement, but in a quest, that is, not in an idol of the future but in a task that can only be described in narrative. If Nietzsche is reluctant to specify the content of the new values he calls for, he is clear enough that these new values must have a new form. In the form of narrative, values cannot fall victim to the sort of metaphysical hypostatization that has been the result of the Socratic turn of philosophy outlined in The Birth of Tragedy.

3.

Dienstag’s own discussion on Cervantes opens with an aside regarding the place of Don Quixote in popular consciousness, domesticated by the view of the 1965 musical reworking in Man of La Mancha. ‘Though I am not concerned here with cultural analysis,’ he states, ‘the reworking that Don Quixote receives in Man of La Mancha is an interesting example of the kind of imperialism of optimism that has succeeded in making pessimism invisible today.’

It is at this point that Dienstag’s reading of Don Quixote intersects with that of Luiz Costa Lima (a figure we have considered before in these pages). For it is this general idea of a domesticated Don Quixote that Costa Lima takes as the starting point of his own exploration of the novel, in a chapter of his book, The Dark Side of Reason: Fictionality and Power (1992), written under the heading: “History of a Ban.” Significantly, Costa Lima opens this chapter with an attack on the view of history that is undergirded by the optimism of progress and the linearity of time:

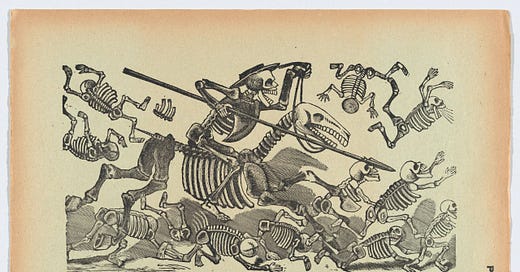

History can no longer be envisaged as a sort of Olympic race in which each generation hands down to the next the torch it received from the previous one; or as a continent crossed by a shining path, it being the case that among natural instincts, most of them selfish and evil, there is one that points in the opposite direction: an infallible thirst for truth. This smug, optimistic conception envelops the world in a reassuring certainty and sees the role of the thinker in unproblematic terms: the athlete who bears the torch of truth.

Against this view, and in the crisis following the abandonment of the medieval world-view, Costa Lima locates the emergence of the problem of fiction. And it is within this emergence that he locates the significance of Don Quixote; in particular, with the protagonist’s madness, which lies with Don Quixote’s inability to distinguish between perception and imagination. Against this is the role of Sancho Panza, whose interactions with Don Quixote inserts an hitherto unknown critical element – what Costa Lima elsewhere calls ‘criticity’ (criticidade in Portuguese), a non-normative act of questioning – into narrative fiction. ‘The space of fictionality in Cervantes assumes a critical stance in the very act of creation,’ Costa Lima states:

For this he must resort to distancing, the author's ability to place himself outside of his narrative. . . . Thus it is important to emphasize that when modern fiction appears, critical activity is seen not as a mere supplement to creation, but rather as an activating part of its makeup. Against the naiveté presupposed by pre-Cervantine fictitiousness, based on the illusion that its own territory is not to be distinguished from that of truth, modern fictionality is based on irony, on distancing, on the creation of a complexity that, without alienating the common reader, does not present itself to him as a form of illusionism.

It is this critical activity at the heart of fiction – initiated by an underlying mimesis, understood not as a static imitation, but as a more dynamic production of difference that allows the necessary distancing from truth – that the process of attempting to ‘control of the imaginary’, to impose a ban on fiction, aims to domesticate. Such a critical activity, in the form of questioning, characterises also the pessimistic intellectual tradition, which accounts also for its association with various literary genres, as in, for example, the essays of Montaigne or the aphorisms Nietzsche; a tradition which, as Dienstag argues, is likewise domesticated or tamed, based upon an ‘imperialism of optimism’; or, through a process of resignation, subject to ‘an act of imagination that discourages further imagination’.

It is in this respect that Costa Lima and Dienstag approach the same ground, albeit from different perspectives.

4.

Aristotle associated mimesis with poeisis, the making of plots or narratives, and it is through his focus on narrative – and the narrative of Don Quixote, in particular – that Dienstag comes closest to bringing to the surface this underlying dynamic of mimesis, albeit without actually naming it as such. Originally, such mimesis was directed, not at the reality of things, but solely at their potentiality. ‘Aristotelian mimesis,’ Costa Lima states,

‘presupposed a concept of physis (to simplify, let us say, of “nature”) that contained two aspects: natura naturata and natura naturans, respectively, the actual and the potential. Mimesis had relation only to the possible, the capable of being created – to energeia; its limits were those of conceivability alone. Among the thinkers of the Renaissance, in contrast, the position of the possible would come to be occupied by the category of the verisimilar, which, of course, depended on what is, the actual, which was then confused with the true.’

It is in this relationship between narratives and potentiality where Dienstag notes that Don Quixote sets off on his quest after reading fables of chivalry, but that in doing so, Don Quixote doesn’t directly imitate or try to replicate the actual events narrated (the natura naturata), but rather the narrative of the events itself (the natura naturans). ‘Since they are narratives, however, and not static images, the imitation of them is not something that can be carried out standing in one place, as it were,’ Dienstag states: ‘Rather, Quixote’s art of living simply consists in imitating, that is living out, the narrative art that describes previous lives he finds admirable. And what is admirable about such lives are not the fixed values of their subjects but their activity, their attempts to change the world.’

In this, Dienstag argues that Alonso, in becoming Don Quixote, elevates his own life to one of ‘narrativisability’, and that it is this precisely this element of the novel that Nietzsche was most drawn to, because it is a feature also of his own narrative intellectual project. ‘Nietzsche did not seek to impersonate the old Zarathustra,’ Dienstag states: ‘Rather, he contended that he could redeem that narrative (that is, in a sense, liberate it) by making it a necessary past to a desirable future, that is, to himself. Similarly, Quixote takes up these old figures, not to lose himself in them, but rather to find himself in them by adding to them, as one adds to a narrative one has inherited.’

It is this process which Dienstag has referred to as redemption (as distinct from reconciliation). Likewise, it is this critical activity that we, as readers of such narratives, are emboldened to undertake:

Quixote’s adventures, properly understood, should not trigger a desire that they be repeated, but could prod us to continue them in the sense Quixote continues, by radically transforming, the narratives that have shaped him. Static norms demand to be affirmed; narrative values ask only to be extended.

In this, the way of life being presented by Don Quixote, one that models itself on the movement of narrative, is that of the quest. And yet, it is a way of life that leads invariably to social and cultural marginalisation. ‘Cervantes emphasizes, as does Nietzsche, that to model one’s life on a quest is to isolate oneself,’ says Dienstag: ‘Even when Quixote is in physical contact with other people, as he often is, the fact that they do not share his perspective leads them to consider him mad.’

5.

But as Costa Lima points out in his own reading of Don Quixote (with a nod to another mimetic character, Hamlet), within this madness there lies a method. And as Dienstag argues, this method is one that, in avoiding resignation to what is given in our quotidian reality, opens us up to redeeming a sense of potentiality and freedom.

For Dienstag, one of the defining characteristics of a pessimist is precisely this openness to potentiality. ‘The pessimist expects nothing,’ he states: ‘thus he or she is more truly open to every possibility as it presents itself. A pessimist can recognize and delight in the fact that we live in a world of surprises – surprises that can only strike the optimist as accidents and mishaps, disturbing they do a preordered image of the world’s continuous improvement.’

And this openness to potentiality leads to a particular understanding of freedom, a ‘pessimistic freedom’, that is ‘not tied to historical outcomes – neither to national projects nor to personal life-plans. Nor can it be tied to institutional arrangements of non-interference or nondomination. Rather, pessimism envisions a democracy of moments for an individual who can neither escape time but is not imprisoned by it either. Freedom for the pessimists is not merely a status but an experience that a time-bound person can aspire to through a certain approach to life… exemplified in questing figures like… Don Quixote.’

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter as it will allow me to write this newsletter more frequently).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

p.s. do I need to spell out the connection between Dienstag’s notion of pessimism and Aurelian Craiutu’s understanding of radical political moderation? Or can you join the dots on your own?