1.

Whenever I think about the art of reading, and how fundamental a practice it is in seeding our culture, I keep coming back to a chapter from Richard Brautigan’s 1964 novel, Confederate General from Big Sur, titled “The Rivets in Ecclesiastes”. It succinctly describes the obsessive degree to which I believe reading should sometimes go in order to consider how a written work is held together.

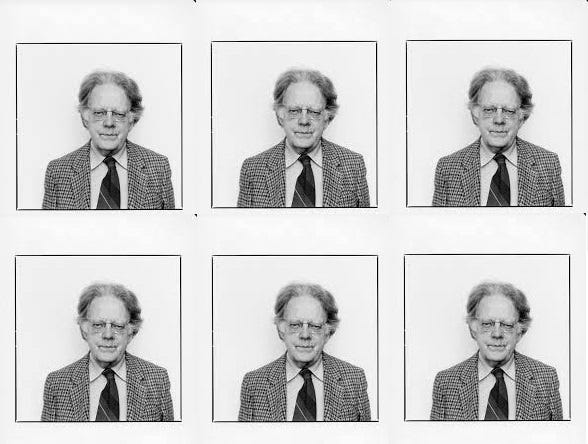

I was, of course, reading Ecclesiastes at night in a very old Bible that had heavy pages. At first I read it over and over again every night, and then I read it once every night, and then I began reading just a few verses every night, and now I was just looking at the punctuation marks.

Actually I was counting them, a chapter every night. I was putting the number of punctuation marks down in a notebook, in neat columns. I called the notebook “The Punctuation Marks in Ecclesiastes.” I thought it was a nice title. I was doing it as a kind of study in engineering.

Certainly before they build a ship they know how many rivets it takes to hold the ship together and the various sizes of the rivets. I was curious about the number of rivets and the sizes of those rivets in Ecclesiastes, a dark and beautiful ship sailing on our waters.

Brautigan then provides the numbers of commas, semicolons, colons, question marks, and periods, across each of the chapters of Ecclesiastes.

I thought I was alone in this obsession until I read Ryan O’Neill’s 2018 collection of stories, The Drover’s Wives. The source story, “The Drover’s Wife”, is a classic Australian yarn, first published by Henry Lawson in 1892. It is the story of a woman and her children, isolated in an outback selection while her husband is away droving sheep, and what happens one night when a snake enters their bush home. It is mythic in its simplicity. Since the 1970’s Australian authors have been engaged in a literary game to rewrite “The Drover’s Wife” in various ways. But it is a game with a serious intent, as it keeps the foundational moment of Australian culture an open and vital question. (For more details, I reviewed O’Neill’s book when it came out, along with a book about this literary game, written and collated by Frank Moorhouse, an early participant and promoter of the game).

O’Neill took the game to its extreme, by writing ninety-nine different versions of Lawson’s story. (When I introduced Ryan O’Neill to Frank Moorhouse over dinner one evening, shortly before O’Neill’s book came out, I told Frank about the ninety-nine versions of “The Drover’s Wife”, and he looked at Ryan, stunned, and said: ‘You’ve won.’) This bravura performance of writing so many different versions of the same story would have been impossible without an underlying and equally bravura performance in reading Lawson’s original story, taking it down to its constitutive parts so it could be rebuilt, again and again, in various ways, with each new version still holding true. My favourite is the version titled “Punctuation”. Taking a step further than Brautigan’s approach to Ecclesiastes, O’Neill simply published the punctuation marks constituting Lawson’s original story, the very rivets holding together the bullock train of Australia’s literary culture.

But there is another figure who has taken something very much akin to this approach and applied it, not simply to this or that individual work of literature, but to the whole of literature. And that is the Canadian literary critic, Northrop Frye.

2.

It would be impossible to do justice to Frye’s body of work here, a career that produced over thirty books across nearly fifty years, all the while teaching at the University of Toronto. So I will focus only on various points of entry into that body of work, and hopefully this will be enough to encourage somebody reading this to take a closer look for themselves. As it happens, this is a corollary to how Frye himself approached literature. In a notebook entry from the early 1950s, where he was first working out his general thoughts which would become his landmark book, The Anatomy of Criticism (1957), he drilled down to the basic experience of reading and its relation to criticism. ‘One of the most familiar facts of literary experience,’ he wrote to himself, ‘is that one’s understanding deepens as well as expands.’ He goes on to explain this with reference to poetry: that the more new poems one reads, not only does one learn more about those particular poems, but one also increases one’s understanding of poetry itself. Likewise with novels and stories, our understanding of individual works can deepen at the same time as our understanding of literature as a whole expands, with each feeding back into the other.

This may seem very obvious, and probably not worth mentioning. But one of the main reasons Frye was such an interesting critic – and this is what distinguished him from others in the field – is that he would constantly return to the basics, to consider the nuts and bolts of the very act of reading, in order to show that the obvious is usually not so obvious at all, and often hides the keys for what one was seeking fruitlessly for elsewhere. He opened his 1962 Massey Lecture series, for example, by stating: ‘I think now that the simplest questions are not only the hardest to answer, but the most important to ask.’

Consider for a moment how much of what has passed – and continues to pass – as literary criticism and literary theory in the academy over previous generations, relies, not on reading literature itself – so ‘one’s understanding deepens as well as expands’ – but with the application of theories and models drawn from disciplines and fields outside of literature, as heuristics and shortcuts to ensure you don’t have to read too deeply or broadly, and in most cases, so you don’t have to read literature at all, the theory or model letting you know in advance what it is you are going to find in this or that novel or short story or poem. This operates by pulling the work into the shallows and restricting its respiratory meaning to being simply an illustration of this or that theory, with the terminal point of reading having been reached, even if the work is killed in the process.

George Orwell likened this process of reading as being like eating cherries for the pips.

Such an application of theory creates the illusion that you now know how to read, and so you can stop reading. In that context, one can appreciate the radical nature of an otherwise simple statement as this (drawn from the same notebook entry as above): ‘I also feel that the obvious place to start looking for a theory of literature is in literature.’ Or, as this idea developed in the published version of The Anatomy of Criticism: ‘Critical principles cannot be taken over ready-made from theology, philosophy, politics, science, or any combination of these.’ That one must not ‘subordinate criticism’ to an ‘external source’, but as a sub-branch of the very literature one is reading.

Frye published The Anatomy of Criticism in 1957, around the moment that the academy systematically ignored everything he said in this, and other, works that he continued to publish over the coming decades. Ignoring the basics of reading literature qua literature came at a price to the humanities, which over recent decades has been reckoning with its own exhaustion. So it is interesting to find, among the wreckage, some figures, such as John Guillroy, in his recent diagnosis of this exhaustion, Professing Criticism: Essays on the Organization of Literary Study (2022), returning to an otherwise obvious (but not so obvious) point: ‘Reading has no terminal point, at which one might say, “Now I know how to read.” Reading is a practice that can be developed indefinitely, that can always be improved and deepened.’

Nowhere in Guillroy’s book, of course, is Northrop Frye mentioned. But the realisation that one can never reach the point of saying, ‘Now I know how to read’ – no matter how literate, intelligent, or credentialed one considers oneself to be – is only a diplomatic way of admitting, ‘I don’t know how to read.’ And that is the necessary admission one must make (if only to oneself, in the cold comfort of your favourite reading chair), before one can even begin to read.

3.

Frye published an essay in the Kenyon Review in 1950, called “Levels of Meaning in Literature”, which became one of his points of entry into writing The Anatomy of Criticism. In the Middle Ages, there was a schema for reading across four different levels, which Frye refers to as the literal, the allegorical, the tropological, and the anagogic. In rehabilitating this for the modern world, Frye dropped the religious connotations – even as Frye himself remained religious, the works marking the culminating point of his career in the 1980s and 90s being The Great Code: The Bible and Literature (1982) and Words with Power: Being a Second Study of the Bible and Literature (1990).

The section from his notebooks, already referenced above, refers to these four levels of meaning, which, although numbered sequentially, are present simultaneously in each act of reading. So I won’t consider these in sequential order, as Frye does, but will begin instead with the fourth level, the anagogic. This is defined by Frye as literature as a whole, as a ‘total order of words’. In the Middle Ages, this was associated with the Mind of God, with the order of words being the one Word. But in his notebooks Frye outlines how, in terms of literature, this can be transposed into a secular theoretical mind, to serve very practical ends:

To make sense of the shape of any subject, you have to assume an omniscient mind. No one mind comprehends the whole of physics, but the subject wouldn’t hang together unless it were theoretically possible for one mind to comprehend it, all at once. And if there is such a thing as “the whole of” physics, the subject must have an objective unification at its circumference. This universal mind is not God, in any religious sense, for it does not necessarily exist: it is necessary only as a hypothesis completing a human mental structure.

(Frye’s analogy with the field of physics is somewhat apt, as that field – along with mathematics and the sciences generally – emerged from the Middle Ages under the auspices of a generalised concept of rationality that was itself initially modelled on the Mind of God.) In the same section of his notebook, Frye suggests two characteristics of this theoretical, or hypothetical, mind: ‘a) that we have no reason to suppose that it differs from other human minds except in the amount of knowledge it has, and b) that we have no reason to suppose that it “exists”...’

This anagogic level outlines the deep linguistic background to any single human being, and to all human beings, as well as the field of literature that sits beyond this or that particular book, or all existing books. ‘The difficulty in understanding this point arises from the confusion of language with dictionary language, and of literature with the bibliography of literature,’ Frye states in his Kenyon Review essay. ‘Language in a human mind is not a list of words with their customary meanings attached, but a single interlocking structure, one’s total power of expressing oneself. Literature is the objective counterpart of this, a total form of verbal expression which is recreated in miniature whenever a new poem is written.’

He is referring here to the potential within each individual human mind, and within each particular poem or novel or short story such a mind may actually read or write – and what happens when these two forces meet in the act of reading.

4.

This may seem a very long way from considering the rivets in the Book of Ecclesiastes, but the fourth, or anagogic, level of meaning counterbalances the first, or literal, level of meaning. This first level refers to the actual sequence of words – and punctuation marks holding those words in a particular fixed pattern – that constitutes any particular literary work. In an unpublished five-volume anthology textbook, The Survey of British Literature, for which Frye was the General Editor, he wrote in his draft introduction, regarding Milton’s prose: ‘Its punctuation alone is worth study, because it is purely rhetorical punctuation, following the natural rhythms of speech, far removed from the pseudo-logical fatuities of modern style manuals.’ In the same draft, referring to Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, Frye states: ‘Here the whole book is welded into unity by a darting associative style, its essential mark of punctuation the dash, which is a sequence of lightning glances at speech, gesture, conscious action, unconscious thought, and author’s comment all in turn.’

The fundamental importance of this reading at the level of the line is exemplified by the confused reception of Frye’s two books (referenced above), sharing the subtitle, The Bible and Literature. He remained adamant that the most important word in that phrase is the conjunction ‘and’, with most people misreading (and so misinterpreting) those books as considering the Bible as literature, or, alternatively, literature as religion. ‘The significance of the “and” was that I was not attempting to isolate the literary features of the Bible, or deal with the “Bible as Literature”,’ he explained in the introduction to the second book, in an attempt to clarify the confused reception of the first book. ‘I wanted to suggest how the structure of the Bible, as revealed by its narrative and imagery, was related to the conventions and genres of Western literature.’

Inattention to this basic level of the sentence, disregarding the actual order of words, and their syntax, can lead you wildly off course.1 Yet again, Frye’s point is that the obvious may prove to be very difficult, especially if you are not aware of the difficulties involved in otherwise simple activities. George Orwell said that seeing what is in front of one’s nose requires a constant struggle. Frye would say something similar regarding the very words on the page in front of your eyes. And this is because, when reading a particular work, our attention is forced in two opposing directions at once, which Frye refers to as the centripetal and centrifugal movements of language.

The former is associated with this first level of reading, internal to the work itself, and how the words and sentences and paragraphs and chapters interlock and hold together. It requires a linear approach, beginning with the first word on the first page and ending with the last word on the final page, with no skimming, no skipping ahead. Frye also calls this a ‘pre-critical’ stage of reading, in that you cannot even begin to critically engage with a work until you have considered it as a whole, complete. And that requires a second reading. A second reading of a work can be more non-linear, in that you can now examine this or that section of a work, a scene or situation, in relation to the whole. We can move forward and backward in our imagination, tracing the contours of a story line, or a particular character development, or consider a particular metaphorical entailment. But these are all anchored in that initial, linear reading.

The centrifugal movement of language goes in the other direction, pointing outside the work, to language generally and culture as a whole. But without this anchor in the centripetal, as a countervailing force, you are likely to spiral without any bearings or co-ordinates within which to orient your reading. Or, for that matter, without any bearings or co-ordinates within which to orient yourself in the world. It is here, of course, that the lure and false promise of much literary theory (and political ideology) lies in wait, foreclosing the centrifugal movement, and denying the necessity of considering the centripetal, while offering you a state of equilibrium between both. But, as John Ralston Saul has said, in another context: ‘On the day that you or I achieve a stable condition of equilibrium, those around us who have been less fortunate will draw one of two conclusions. Either that we are dead of that we have slipped into a state of clinically diagnosable delusion.’

The point is to hold these two forces of language in tension. Focusing on only one or the other is to perform a ‘half-reading’, as Frye describes it. ‘Failure to grasp centrifugal meaning is incomplete reading,’ he states, ‘failure to grasp centripetal meaning is incompetent reading.’

5.

This second reading of a work, following the ‘pre-critical’ stage, the first reading, takes us also into the second and third levels of meaning. These middle levels of meaning are, for Frye, the stages of criticism-proper. The second and third levels delimit the field of literary criticism, but Frye places these in context of the first and fourth levels, the literal and the anagogic, which are otherwise beyond the scope of criticism, but constitutive of its practice.

This field of criticism operates over two levels, which in his notebooks Frye distinguishes as ‘lower’ and ‘higher’ criticism. But these are metaphors only and not value judgements, such that the second is deemed better or more valuable than the former. The whole point of Frye’s work is that all four levels of meaning are important, but within that, the sequence from first to fourth, and within the field of criticism, from lower to higher, is a necessary sequence. The latter are grounded in the former, and the former are the essential points of entry into the latter. ‘Bastard higher criticism’, he notes, is one not adequately grounded in ‘lower (or prior) criticism.’

Lower criticism refers to forms of scholarship associated with ‘editing, legitimate source-hunting & biography.’ This context is located in the body of work associated with a particular writer. I consider this the foundational work upon which ‘higher’ forms of criticism can be erected, which then compare this or that particular work with other works within the field of literature, and from that perspective, to our culture as a whole.2 For Frye, this centrifugal force spirals outward from the second through to the fourth levels of meaning, the biographical (level two) expanding into the historical (level three), which expands again into the anthropological (level four). The structural elements of a particular work (level two) likewise expand into the functional elements, regarding how that particular work relates to other works operating within certain conventions and genres (level three), which expands into archetypal and mythic forms operating within literature as a whole (level four). ‘The fourth level is beyond real criticism,’ Frye wrote in his notebooks: ‘here the critic proper gives place to the real reader, who can assimilate literature to the total body of culture.’

6.

One of the misunderstandings surrounding Frye’s work is that, coming out of the 1940s and 1950s, it was associated with the school of “myth criticism”, which, as with all schools of thought and intellectual trends and fashions, came and went. And with it, Frye’s work. But his work, because it was based on literature qua literature, and not on this or that theory or school of thought, is more expansive and inclusive than most other approaches to literature, then or since. ‘When I published a study of Blake in 1947, I knew nothing of any “myth criticism” school, to which I was told afterward I belonged,’ he wrote in 1975. ‘I simply knew that I had had to learn something about mythology to understand Blake.’ His study of Blake was his first book. Ten years later he published his second book, on which his reputation was founded, The Anatomy of Criticism. But even here – as a testimony to how important it is to read centripetally, in the first instance – his theory of myths is only one of four essays, with each essay outlining a distinct and necessary way to approach a work of literature. The other three essays outline historical, ethical, and rhetorical forms of criticism, concerned with the modes, symbols, and genres of literature, respectively. The scope of his thinking was to always be open to bringing in anything that helped increase his understanding of literature generally, or of this or that work in particular, while other approaches in the field tended to be more reductive, moving from one narrow extreme to the other: uncovering the author’s intention, or ignoring the author altogether; formalist readings, without reference to content or historical or cultural context, or else considering a work as entirely determined by such historical or cultural contexts; and so on.

But what continues to be important in Frye’s work, is that regardless of what school of thought or particular theory is at any moment in the ascendency, there is always something in Frye’s work to act as a necessary corrective, to lead the stray professional reader or critic back to literature. But what is more important about Frye’s work is that he understood that reading as a critic or an academic is always grounded in what used to be called ‘common reading’. And that form of reading, among the general populous, outside of the academy, is of fundamental importance to the vitality of our culture. The John Guillroy quote, stated above, regarding reading having no terminal point, was taken from a chapter titled, “The Question of Lay Reading”, in which he argues that ‘lay reading is a condition of professional reading.’ Most professional readers have lost that sense, which is accounted for the fact that, in practice, the habit is still to reach for this or that theory, or rubric of theories, to alleviate the effort of actually having to read. Frye started with that sense, and the vitality of his work is that he kept returning to this sense of reading as a good internal to itself.

What Frye reminds us is that the greatest mistake we can make when we pick up a book is to think we already know what we are doing, and that each time we have to learn to read all over again.

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

Had critics, for example, actually read Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Purloined Letter” at this basic level, we would know that every character in the story knew the contents of the stolen letter, and we would have been spared decades of onanistic speculation about empty signifiers.

My reading of Albert Camus’ The Plague, for example, (which begins here) was very much grounded in such biographical contexts, reconstructing the composition of the novel across a discrete period of time, in a particular historical and cultural context, drawing on personal, literary, and intellectual sources available to Camus himself, while also examining his full body of work, novels, essays, notebook entries, and so on). I even had a section which explicitly drew on the work of Frye to help orient Camus’ novel into various literary forms and genres (read here).

“Ignoring the basics of reading literature qua literature came at a price to the humanities, which over recent decades has been reckoning with its own exhaustion. “ This is so true. Thanks for a wonderful article.

Bravo, Matthew. In my experience, many people struggle with what I take to be the cornerstone insight of all of Frye’s theorizing and criticism: namely, that there is a total order of words that is as real as is what we call the natural order. Indeed, after Blake, Frye imagined that the order of words and the imagination itself are interpenetrating forms of reality in which reality itself—reality with a big R—is created and continually recreated. All other expressions of reality find their form in the dialect or dialogue of the imagination and the Word.

Expressed as I have expressed it here, no wonder no one understands Frye’s first axiom, as it were. And yet, what I am getting at, the ontological primacy of verbal symbols and the imagination, is, if my understanding of Frye is vital, the insight on which all of his other insights ultimately depends and the consummate meaning to which they lead.