1.

Freudian psychoanalysis is more than a century old. Although it could be argued that it has never really gone anywhere, it has of late somehow, inexplicably, returned among a younger generation (see here and here). But its place has not gone uncontested, and even today the debates repeated ad nauseam regarding its truth or falsity are the same ones which met The Interpretation of Dreams when it was first published in late 1899. The resilience of psychoanalysis is not hard to find, however, for it is theoretically sustained by an idea which turns resistance to it into a form of legitimation. Its critics may therefore be as responsible for its continued appeal as its staunchest supporters. The challenge is how to critically evaluate psychoanalysis without assuming one’s position within the usual debates regarding its truth or falsity.

Norbert Elias, considering the sociology of knowledge, may provide us with a possible starting point. In his 1987 work, Involvement and Attachment, Elias points out that it is only through a ‘peculiar blockage of [our] power of imagination’ that we ‘cannot imagine how much of all [we] know it is possible for human beings not to know’. In other words, the conditions under which we come to know something – in this instance, psychoanalysis – are preceded by the conditions of not-knowing:

Without the reconstruction of the former, of the condition of not-knowing, the condition of knowing and thus the knowledge process itself must remain incomprehensible. The difficulty is that once a specific item of knowledge has established itself as highly reality-congruent in a society, people acquire this knowledge as children and it appears obvious to them. They forget that it came to them as a heritage from ancestors who did not know and could not know, or did not know clearly, what they themselves know as a matter of course.

This difficulty is more prevalent, however, with regards to psychoanalysis as an established ‘reality-congruent’ body of knowledge, because its very theoretical structure accommodates such states of ‘not-knowing’ within the conditions of its ‘knowing’ – in the relationship between the unconscious and conscious mind, for example – and it incorporates these conditions within the very developmental structure of children – such that it seems as though ‘people acquire this knowledge as children and it appears obvious to them’ – even, or especially, when they resist it.

Attempting to reconstruct what Elias calls the ‘knowledge process’ between states of not-knowing and knowing – that is, the conditions under which psychoanalysis as a body of knowledge has historically and intellectually developed – it will be necessary to attend first to overcoming this ‘peculiar blockage of [our] power of imagination’.

It is a notable fact regarding Freud’s works that the high place images hold in his discussions, either as a topic under investigation (especially in dream symbols), or used as a means through which to approach these investigations (as in his analogical style of discourse), is in direct proportion to the low esteem in which he holds our image-making capacities. Instead of speaking about the imagination in a positive light, Freud prefers to speak pejoratively about ‘phantasies’, which he connects in waking life to day-dreams, and in our sleep, with the formation of dreams, all of which are associated with elements of wish-fulfilment stemming from a certain dissatisfaction regarding our relation to the real world. In this, all images in psychoanalytic discourse are contained within allegories which lead inevitably back to an overarching, formal theoretical model; a model which, as Elias would say, aims at being ‘reality-congruent’.

This observation raises the question of how we are to understand the use of images in the formation of aspiring ‘reality-congruent’ discourses, such as psychoanalysis. The best place to start may be by examining a particular image in action and, if possible, to draw from this some general principle which may then be tested in other cases.

2.

Robert Musil, in the novel, The Man Without Qualities (1930) provides us with such an image: the doorway. ‘If one wants to pass through open doors easily, one must bear in mind that they have a solid frame: this principle,’ the narrator informs us, ‘is simply a requirement of the sense of reality. But if there is such a thing as a sense of reality – and no one will doubt that it has its raison d’être – then there must also be something that one can call a sense of possibility’. Here Musil also provides us with an interesting working hypothesis as to how images and reality may be interrelated: images provide a sense of possibility which necessarily presupposes a sense of reality. This also provides us with a certain perspective.

Luiz Costa Lima, a Brazilian intellectual, in his 1996 book, The Limits of Voice, complements this point with reference to the theatre. ‘Perspectivisation itself rests on the soil that remains stable,’ he writes: ‘For instance, if one is to be moved to tears, one must be sure that one is at the theatre. If the theatre is to question the world, the very existence of the theatre must remain unquestioned.’ In other words, the physical reality of the theatre, the stalls and the stage – like Musil’s doorway – all frame the imaginary events created in that enclosed space – or through that solid doorway – and enable us to engage with them at the level of the imaginary.

For Costa Lima, this aspect of the imagination is related to the operation of mimesis (as we have discussed previously here). Our commonplace understanding of mimesis has come down to us through the Latin translation, imitatio, during the Renaissance rediscovery of classical texts, and has henceforth been rendered simply as ‘imitation’; or, more precisely, as ‘imitation of the real world’. In this, the imagination is considered as being subordinate to reality, and of only secondary importance.

But this is not necessarily the case. Through a series of ground breaking works, beginning with Control of the Imaginary (1989), Costa Lima has been arguing that this meaning of mimesis – as simply imitation of the real – is incorrect. Originally, mimesis was directed, not at the reality of things, but solely at their possibility. ‘Aristotelian mimesis,’ Costa Lima states,

presupposed a concept of physis (to simplify, let us say, of “nature”) that contained two aspects: natura naturata and natura naturans, respectively, the actual and the potential. Mimesis had relation only to the possible, the capable of being created – to energeia; its limits were those of conceivability alone. Among the thinkers of the Renaissance, in contrast, the position of the possible would come to be occupied by the category of the verisimilar, which, of course, depended on what is, the actual, which was then confused with the true.

The consequences of this, as Costa Lima argues, are far reaching. Mimesis, rather than being simply an imitation of reality, is only made operational through differentiating from reality. In this, it retains a sense of reality only to the degree that it is a frame through which the possible can emerge. Like Musil’s doorway, for example.

3.

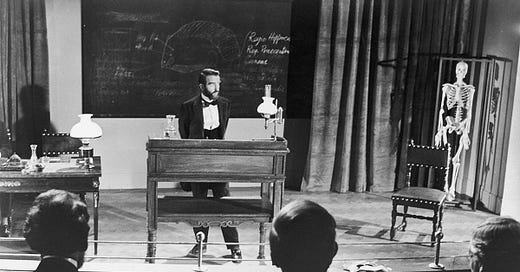

Over two winter terms between 1915 and 1917, in Vienna, Freud delivered a series of public lectures, later published as Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. Lecture XIX, “Resistance and Repression”, marks the point in the course where Freud first attempts to move from the descriptive meaning of ‘the unconscious’ to a systematic meaning of the same term.

‘The crudest idea of these systems,’ he tells his audience, ‘is the most convenient for us – the spatial one.

Let us therefore compare the system of the unconscious to a large entrance hall, in which the mental impulses jostle one another like separate individuals. Adjoining this entrance hall there is a second, narrower, room – a kind of drawing-room – in which consciousness, too, resides. But on the threshold between these two rooms a watchman performs his function: he examines the different mental impulses, acts as a censor, and will not admit them into the drawing-room if they displease him. You will see at once that it does not make much difference if the watchman turns away a particular impulse at the threshold or if he pushes it back across the threshold after it has entered the drawing-room. This is merely a question of the degree of his watchfulness and of how he carries out his act of recognition. If we keep to this picture, we shall be able to extend our nomenclature further. The impulses in the entrance hall of the unconscious are out of sight of the conscious, which is in the other room; to begin with they must remain unconscious. If they have already pushed their way forward to the threshold and have been turned back by the watchman, then they are inadmissible to consciousness; we speak of them as repressed. But even the impulses which the watchman has allowed to cross the threshold are not on that account necessarily conscious as well; they can only become so if they succeed in catching the eye of consciousness. We are therefore justified in calling this second room the system of the preconscious. In that case becoming conscious retains its purely descriptive sense. For any particular impulse, however, the vicissitude of repression consists in its not being allowed by the watchman to pass from the system of the unconscious into that of the preconscious. It is the same watchman whom we get to know as resistance when we try to lift the repression by means of the analytic treatment.

In making his case for the systematic meaning of the unconscious, Freud is trying to legitimate the psychological descriptions he made in the first term of lectures, in identifying parapraxis, symptomatic actions and the interpretation of dreams. In these earlier lectures Freud put forward an hypothesis that these phenomena are best understood as manifest material created by some latent source. Psychoanalysis is put forward as a method for identifying these latent sources and a way of explaining the process of formation that leads from its latent to its manifest state.

The imagery Freud calls upon to introduce the possibility of these underlying mental systems and mechanisms hinges on an image of ‘the doorway’, and its metaphorical entailments. Here Freud is trying to lead his audience out of the realm of psychoanalysis as only a possibility, which the first term of lectures has established, and into the realm of psychoanalysis as a reality, which is the purpose of this second term of lectures. To achieve this, Freud must assert the legitimacy of the unconscious system and the mechanism of repression, not as being useful metaphors, but as being real domains and real processes functioning in the depths of the human mind.

This situation calls for an analysis of space deployed at three distinct levels. First, there is the physical reality of the lecture theatre, in which Freud stood before a live audience of the Vienna Psychiatric Clinic. Second, there is the imaginary space created by Freud’s discourse, produced through the rhetorical imagery he deploys in order to create the effect of the possibility of psychoanalysis. Finally, there is a third space, a hypothetical space, in which Freud attempts to shift his discourse away from being imaginary toward achieving a certain degree of ‘reality-congruency’.

Here it may be seen that my previous introduction of certain images employed by Robert Musil and Luiz Costa Lima was by no means a random choice. For it is through the spatial imagery associated with the doorway that Freud first attempts to make the leap which will allow this third, hypothetical space, to become a legitimate, autonomous space, not just distinct from these first two spaces, the physical and the imaginary, but holding a certain sway over how the imaginary operates within the realm of the physical. To achieve this, Freud has to ensure that the possibilities suggested by his image of the doorway have, as Musil would say, ‘a solid frame’. This will determine – if we consider Costa Lima’s theatre – whether Freud, standing before his live audience, is indeed delivering a lecture, with consequences outside its stalls, or if, rather, he is simply delivering a soliloquy in a one-man drama of his own devising.

4.

Considering the importance of the shift from the descriptive to the systematic mode of discourse, it is significant to note that at the very moment in which Freud asserts the systematic, he immediately retreats into the descriptive, by presenting his case via spatial imagery associated with the image of the ‘door’. Why? In the years preceding the Introductory Lectures, Freud presented three essential arguments, in an effort to give this possibility of psychoanalysis a sense of reality. These are the necessary points of entry into psychoanalysis. The first point of entry is also the basic premise of The Interpretation of Dreams: that beneath the manifest dream-content, which we have access to, there are certain latent thoughts, which we do not have access to, but from which the manifest dream is created, albeit in a disguised form. To support this Freud argues that the formation of the manifest dream-content is brought about through a mechanism of repression: this marks the second point of entry into psychoanalysis. To show how this mechanism of repression works Freud argues that the human mind is divided into diametrically opposed primary and secondary processes; and this argument becomes the third point of entry into psychoanalysis. These points of entry are all recalled in his Introductory Lectures (see Lecture VII, in the first term, and Lecture XVIII and XIX, in the second term).

Freud argues that it is the relation between the primary and secondary processes that initiates the mechanism of repression, that in turn results in, on the one hand, the suppression of certain thoughts, and on the other hand, the manifestation of the actual (manifest) dream-content. In short, these three points of entry mark the proposed theoretical field which we have already seen Freud introduce in his Introductory Lectures via the spatial imagery of the two rooms, the doorway between them, and the watchman overseeing the comings and goings therein.

Freud bases the mechanism of repression on the claim that the human mind is divided into two oppositional domains. But on what does he base the claim that the human mind is divided into these two domains? It is by returning to his starting point that Freud looks for his continuing support. ‘Whenever I begin to have doubts of the correctness of my wavering conclusions,’ Freud later states, in his New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, ‘the successful transformation of a senseless and muddled dream into a logical and intelligible mental process in the dreamer would renew my confidence of being on the right track’.

What can be discerned here, of course, is that the basic hypothetical field which Freud is trying to establish through metaphor assumes the shape of a circle and turns back upon itself. The explanation for the formation of the manifest-dream content lies in the mechanism of repression, the explanation for which lies in the division of the mind into a primary and secondary process, the explanation for which is found in the formation of the manifest-dream content, and so on. The result of this may be seen in Lecture XIX when, unable to establish a solid frame for his arguments, unable to locate a secure ground for his systematic meaning of the unconscious, Freud reverts back to the descriptive meaning of the term and its associated imagery. ‘The crudest idea of these systems,’ he states, ‘is the most convenient for us – the spatial one. Let us therefore compare the system of the unconscious to a large entrance hall . . . .’ In other words, Freud fails to adequately emerge from the imaginary (second) space in order to establish independently a third, psychoanalytic, space.

5.

In the early 1890s, prior to The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud researched a book with Joseph Breuer, titled Studies in Hysteria (1895). From their clinical practice, these two men put forward a new theory on the aetiology and potential cure of hysteria. It is out of this work, and after breaking with Breuer, that Freud first saw the possibility of psychoanalysis. Significantly, in the theoretical chapters of Studies in Hysteria, written by Breuer, the basic ideas which Freud would later develop are introduced via spatial imagery. However, Breuer makes the following qualification:

If it seems to us, as it does to Binet and Janet, that what lies at the centre of hysteria is a splitting off of a portion of psychical activity, it is our duty to be as clear as possible on this subject. It is only too easy to fall into a habit of thought which assumes that every substantive has a substance behind it – which gradually comes to regard ‘consciousness’ as standing for some actual thing; and when we have become accustomed to make use metaphorically of spatial relations, as in the term ‘sub-consciousness’ we find as time goes on that we have actually formed an idea which has lost its metaphorical nature and which we can manipulate easily as though it was real. Our mythology is then complete.

All our thinking tends to be accompanied and aided by spatial ideas, and we talk in spatial metaphors. Thus when we speak of ideas which are found in the region of clear consciousness and of unconscious ones which never enter the full light of self-consciousness, we almost inevitably form pictures of a tree with its trunk in the daylight and its roots in darkness, or of a building with its dark underground cellars. If, however, we constantly bear in mind that all such spatial relations are metaphorical and do not allow ourselves to be misled into supposing that these relations are literally present in the brain, we may nevertheless speak of a consciousness and a subconsciousness. But only on this condition.

Freud’s eventual break with Breuer may be considered in part to be over this question of the use of spatial images: Breuer sees the explanation for hysteria as being localised to this particular ailment and only partial, relying perhaps too much on metaphor; while, for Freud, the explanation regarding hysteria have a broader significance, perhaps covering all human psychical phenomena, and one on which there is a legitimate ground of certainty beyond the use of metaphors. And yet, as we have already seen, in laying the ground for his initial theoretical field of explanation, this ‘doorway’ into psychoanalysis, Freud has reverted back to the descriptive meaning of the ‘unconscious’, and where he tries to leave metaphor behind he simply circles back and reoccupies his metaphorical starting point. In other words, Freud has, ignoring Breuer’s qualification, allowed himself ‘to be misled into supposing that these relations are literally present’.

6.

Considering this third, hypothetical space – the theoretical field of psychoanalysis – as not being possible, allows us to attend to what Norbert Elias refers to as ‘the conditions of not-knowing’ which precedes the possibility of psychoanalysis and the conditions out of which it emerged. In removing this third space, we are still left with the first two spaces to contend with, the physical and the imaginary. Here we can ask: where did Freud derive the spatial imagery for the systems of the mind announced in Lecture XIX? He says that it was ‘the most convenient for us’, but how true this statement is can only be appreciated if we go back a few lectures, to Lecture XVI, on the topic of “Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry”.

In the first term of lectures in the winter of 1915-16, Freud discussed parapraxis and his theory of dreams. Significantly, Lecture XVI is the opening lecture of the second term of his course on psychoanalysis, in the winter of 1916-17. It is where Freud harkens back to his previous discussions and revisits the idea of symptomatic actions. For Freud, seemingly purposeless actions are not purposeless at all; they have a sense, and what’s more, they point the way to an understanding of more significant psychical phenomena. As he tries to assert in his first term of lectures: psychoanalysis itself is founded on the attempt to understand such phenomena.

Here is the anecdote Freud tells, in Lecture XVI, by way of explanation, and as a point of entry into his second term of lectures: ‘I have had the ordinary door between my waiting-room and my consulting- and treatment-room doubled and given a baize lining,’ Freud tells his audience:

There can be no doubt about the purpose of this arrangement. Now it constantly happens that a person whom I have brought in from the waiting-room omits to shut the door behind him and almost always he leaves both doors open. As soon as I notice this I insist in a rather unfriendly tone on his or her going back and making good the omission – even if the person concerned is a well-dressed gentleman or a fashionable lady. This makes an impression of uncalled-for pedantry. Occasionally, too, I have put myself in a foolish position by making this request when it has turned out to be a person who cannot touch a door-handle himself and is glad if someone with him spares him the necessity. But in the majority of cases I have been right; for anyone who behaves like this and leaves the door open between a doctor’s waiting-room and consulting-room is ill-mannered and deserves an unfriendly reception. But do not take sides over this until you have heard the sequel. For this carelessness on the part of the patient only occurs when he has been alone in the waiting-room and has therefore left an empty room behind him; it never happens if other people, strangers to him, have been waiting with him. In this latter case he knows quite well that it is in his interest not to be overheard while he is talking to the doctor, and he never fails to shut both doors carefully.

Thus the patient’s omission is neither accidentally nor senselessly determined; and indeed it is not unimportant, for, as we shall see, it throws light on the newcomer’s attitude to the doctor. The patient is one of the great multitude who have a craving for mundane authority, who wish to be dazzled and intimidated. He may have inquired on the telephone as to the hour at which he could most easily get an appointment; he had formed a picture of a crowd of people seeking help, like the crowd outside one of Julius Meinl’s branches. He now comes into an empty, and moreover extremely modestly furnished, waiting-room, and is shocked. He has to make the doctor pay for the superfluous respect with which he had intended to offer him: so – he omits to shut the door between the waiting-room and the consulting-room. What he means to say to the doctor by his conduct is: ‘Ah, so there’s no one here and no one’s likely to come while I’m here.’ He would behave equally impolitely and disrespectfully during the consultation if his arrogance were not given a sharp reprimand at the very beginning.

Freud gives this a psychoanalytic explanation. The ‘symptomatic action’ Freud is examining here originates in his potential patients, coming into his offices for the first time. Freud has discerned, firstly, that a seemingly purposeless act – such as leaving a door open or shut – may be regarded as symptomatic of a person’s attitude toward another person in a given situation – in this case, to Freud himself; secondly, he suggests that the origin of this action is unknown to his potential patient. As Freud concludes his presentation of this example:

The analysis of this small symptomatic action tells you nothing you did not know before: the thesis that it was not a matter of chance but had a motive, a sense and an intention, that it had a place in an assignable mental context and that it provided information, by a small indication, of a more important mental process. But, more than anything else, it tells you that the process thus indicated was unknown to the consciousness of the person who carried out the action, since none of the patients who left the two doors open would have been able to admit that by this omission he wanted to give evidence of his contempt. Some of them could probably have been aware of a sense of disappointment when they entered the empty waiting room; but the connection between this impression and the symptomatic action which followed certainly remained unknown to their consciousness.

Freud’s interpretation of the symptomatic action of his incoming patients is that they are displaying – through the act of leaving the door open – their ‘contempt’ for Freud’s authority as a doctor. Indeed, this amounts to a display of contempt for the legitimacy of psychoanalysis itself, and to Freud as its originator.

I have already argued, however, that the explanation on which such ‘symptomatic actions’ are based probably does not extend beyond the spatial metaphors used to describe this phenomena, as in Lecture XIX. But if we remove this psychoanalytic explanation from the scene, what we are left with is a clear example of Musil’s principle regarding the interrelationship of the image and the reality of ‘doorways’, and one which perhaps says more about their creator, Freud, than it does about his incoming patients. For, as it may have already been intuited, the images used to describe the workings of the human mind form a direct analogy with Freud’s actual offices; thus exposing how Freud’s own conscious imagination operates within the physical limitations of his own office, phantasies of his own authority. Here Freud himself assumes the role of the watchman at the door between the two rooms within this office. Freud’s actions may therefore be interpreted such that his initial reprimand – his insisting ‘in a rather unfriendly tone on his or her going back’ and closing the door – is an effort to assert both his personal authority, and the authority of psychoanalysis in general.

But this is already known to Freud, who admits of his action that the incoming patient ‘would behave equally impolitely and disrespectfully during the consultation if his arrogance were not given a sharp reprimand at the very beginning’. In Freud’s terms, his own behaviour is directed by a conscious intention: to assert authority. It may also be this conscious intention in Freud, and not any ‘unconscious’ intention in his incoming patients, which may be responsible for his initially considering the patient’s omission in closing the door as being an indication of their lack of respect for both himself and for psychoanalysis.

Turning once more to Lecture XIX, the legitimacy of the systematic meaning of the term ‘unconscious’ rests on the assumption that the two domains of the mind remain separate and, in fact, in opposition to each other. The power of the unconscious loses its explanatory power if its impulses – ‘like separate individuals’ – are allowed to freely shuttle back and forth between the two domains; likewise, Freud considers his authority lost if his consulting-room is not separated from the waiting-room by a closed door. Freud even goes so far as to have ‘the ordinary door between my waiting-room and my consulting- and treatment-room doubled and given a baize lining. There can be no doubt about the purpose of this arrangement’ (italics mine).

The legitimacy of the mechanism of repression in the formation of the human personality also rests on this division being maintained. This maintenance requires the services of a ‘watchman’ to activate the mechanism of repression where it sees fit. In the analogy, and in ensuring the legitimacy of the systematic unconscious, it is Freud himself who has adopted this role; in doing so, he ensures also the legitimacy of the mechanism of repression.

That Freud identifies himself with such a watchman is alluded to in another document, his earlier meta-psychological paper on repression. As Freud states in this paper, in discussing the difference of the repressive mechanism between an idea being pushed back from consciousness and an idea being held back from becoming conscious: ‘The difference is not important; it amounts to much the same thing as the difference between my ordering an undesirable guest out of my drawing-room (or out of my front door) and my refusing, after recognizing him, to let him cross my threshold at all’. This, of course, echoes his statement from Lecture XIX: ‘You will see at once that it does not make much difference if the watchman turns away a particular impulse at the threshold or if he pushes it back across the threshold after it has entered the drawing-room.’

However, in the current situation, regarding his potential patients crossing his threshold, Freud is doing anything but expelling them from his room; if anything, he is ensuring that their exit is blocked. So the question remains: in which domain is this potential patient now located? In Lecture XIX, Freud explains how ‘the watchman performs his function: he examines the different mental impulses, acts as a censor, and will not admit them into the drawing-room if they displease him.’ In Lecture XVI, Freud tells how such people are ‘ill-mannered and deserve an unfriendly reception.’ His response is to disallow them a view of the waiting-room; just as the watchman disallows admittance into the drawing-room. I would therefore suggest that Freud’s treatment-room is analogous with the unconscious; indeed, it is what in Lecture XIX is described as ‘the entrance hall of the unconscious’. Certainly for most people during this period, it was in Freud’s treatment room that they could be said to have supposedly ‘entered’ the unconscious for the first time.

The reason for all this may become clear if it is kept in mind that Freud is viewing the incoming person as though they are a potential patient and labouring under some degree of neuroses. The assumption he is working under – and by which he feels the need to assert his authority – is that the person is in need of psychoanalytic treatment and so must be in some respect already repressed. It could be argued that Freud is simply ensuring this fact by acting out the procedure that would necessarily lead the patient to his treatment-room in the first instance – ‘to begin with they must remain unconscious.’ By ordering them to close the door Freud is indeed blocking their exit, but he is doing so through a procedure which first imposes a blockage on the mimetic operations of their imagination; and in doing so, he is offering them only one way out: through psychoanalysis.

7.

It should come as no surprise to discover that this procedure which Freud acts out in his own offices, and which he reports in Lecture XVI, at the very threshold of needing to convince his audience of the systematic legitimacy of psychoanalysis, extends also to the rhetorical structure of the Introductory Lectures in their entirety. In the opening statements of Lecture I, soon after his audience has entered the theatre first the first time, Freud offers this ‘sharp reprimand’:

Do not be annoyed, then, if I begin by treating you in the same way as these neurotic patients. I seriously advise you not to join my audience a second time. To support this advice, I will explain to you how incomplete any instruction in psychoanalysis must necessarily be and what difficulties stand in the way of your forming a judgement of your own upon it.

This first lecture concludes with Freud reasserting his ‘right to reject without qualification any interference by practical considerations in scientific work, even before we have enquired whether the fear which seeks to impose these considerations on us is justified or not.’ In other words, Freud treats his audience (and his readers) as if they were neurotic and already repressed. Such a rhetorical strategy shifts the onus of proof onto the patient (or reader) and away from Freud. For, as Freud also states in the opening moments of his Introductory Lectures, in explaining how to act with a neurotic patient: ‘We point out the difficulties of the method to him, its long duration, the efforts and sacrifices it calls for; and as regards its success, we tell him we cannot promise it with certainty, that it depends on his own conduct, his understanding, his adaptability and his perseverance’ (italics mine). And so begins the first term of Freud’s Introductory Lectures, proceeding with the descriptive mode of discourse, into parapraxis, symptomatic actions and the interpretation of dreams. In other words, in the physical space of the theatre, Freud proceeds to impress upon his audience the imaginary space associated with the possibility of psychoanalysis (rhetorically devised to prohibit any alternative imaginary), in preparation for asserting the legitimacy of the theoretical space of psychoanalysis to emerge.

Are we at all justified in analysing Freud’s own statements in this way, by turning them back on their author? Two reasons suggest that we are. First, if psychoanalysis is to be considered universally legitimate, then no one should be exempt from its reach. Specifically, its originator does not occupy a privileged position; but more generally, this means that analysts are not beyond the purview of such analysis. And second, because the very origins of psychoanalysis are located in Freud’s own self-analysis. Indeed, the inaugural dream of the psychoanalytic movement – that of Irma’s Injection – is itself the analysis of one of Freud’s own dreams, analysed by Freud himself.

The self-analysis of the dream of Irma’s Injection is significant to our current discussion for a number of reasons. Like our analysis of Freud’s offices, and like the rhetorical structure of the Introductory Lectures, the dream of Irma’s Injection is concerned with an effort to assert both Freud’s personal authority, and the authority of psychoanalysis in general. What is remarkable about this dream, however, is that it predicates the authority of psychoanalysis solely upon Freud’s personal authority. In fact, the dream itself was instigated, Freud tells us in the preamble, by a friend accusing him of only incompletely psychoanalysing one of his patients (Irma). Later that night, just before bed, he wrote out Irma’s case history for another colleague, ‘in order to justify myself’. Then he presents his dream, followed by the dream interpretation, in which he admits that the background to the dream material was a collection of occasions in his own past in which he may have been accused of lacking ‘medical conscientiousness’. In the final analysis, the dream provided Freud with a way to shift the responsibility of these occasions, and especially of Irma’s own treatment, away from himself, thus leaving his personal authority intact. This outcome is asserted in order to demonstrate Freud’s underlying thesis that the dream is a fulfilment of a (unconscious) wish. Our own, non-psychoanalytic, thesis may be expressed in similar terms, but here the dream itself is not the fulfilment of a wish, but rather the dream-analysis and the method upon which it is built is the fulfilment of a (conscious) wish: to assert personal authority.

Considering this, it is a remarkable feature of Freud’s dream analysis that it is itself incomplete. The interpretation only extends as far as the previous days residues and its more easily accessible pre-conscious associations. Not only does Freud not delve into the unconscious at any point, he doesn’t even need to go so far in order to attribute a final meaning to the dream – the fulfilment of a wish to assert his personal authority – and to thereby assert the authority of the psychoanalytic method. In other words, Freud offers an incomplete interpretation of a dream which, by his own account, was instigated by an accusation that he had only incompletely psychoanalysed one of his own patients.

In the conclusion to his analysis of Irma’s Injection, Freud diverts us from considering this incompleteness (what he calls his ‘reticence’) by offering his usual ‘sharp reprimand’ to anyone who should question his authority: ‘If anyone should feel tempted to express a hasty condemnation of my reticence, I would advise him to make an experiment of being franker than I am. For the moment I am satisfied with the achievement of this one piece of fresh knowledge’. He leaves it to a footnote to his own analysis for a more interesting explanation for this incompleteness: ‘There is at least one spot in every dream at which it is unplumbable – a navel, as it were, that is its point of contact with the unknown’. A remarkable admission, especially if we recall that the authority of psychoanalysis rests upon its advertised ability to plumb such depths of the unknown. Toward the end of The Interpretation of Dreams, this image of the ‘navel’ is repeated:

There is often a passage in even the most thoroughly interpreted dream which has to be left obscure; this is because we become aware during the work of interpretation that at that point there is a tangle of dream-thoughts which cannot be unravelled and which moreover adds nothing to our knowledge of the content of the dream. This is the dream’s navel, the spot where it reaches down into the unknown.

Regarding this, Luiz Costa Lima, in a footnote in Control of the Imaginary, states:

In a certain sense Freud defends himself from his own discovery through the reservation that the “navel” can be ignored because it adds nothing to interpretation. Had he not so stipulated, we could say that the navel can be seen as the limit point of a semantically motivated interpretation. The navel would, then, set the scene for the imaginary, i.e., for that which has no redeemable semantic basis of its own. But it surely would not be a part of the analyst’s task to analyse the dream as a discourse that includes imagination, for, were that to be the case, he or she would be prevented from postulating the possibility of a correct, true interpretation of the dream, as Freud does.

This observation supports what we have already considered as existing behind Freud’s defensive rhetoric and thus confirms the general aim of this essay. It is significant to note that at the time of The Interpretation of Dreams Freud is still operating under the descriptive sense of the unconscious and is thereby ‘prevented from postulating the possibility’ of psychoanalysis in any systematic way. Thus the inaugural dream analysis of the psychoanalytic enterprise remains incomplete, stalled at the ‘limit point’ where it abuts the edges of the imaginary. This then marks the background against which the Introductory Lectures are set and, against which, Freud attempts to leap from the descriptive to the systematic sense of the unconscious, in an effort to reassert this possibility; but at that same moment, Freud reverts to the descriptive meaning of the term and its associated imagery, his discussion foundering in a circularity of metaphor.

Here we are left with the physical space of the lecture theatre, with Freud standing before a live audience of the Vienna Psychiatric Clinic. There is an imaginary space produced by the rhetorical imagery he deploys in discourse, which creates an effect of the possibility of psychoanalysis. However, unable to ensure that this ‘doorway’ has a ‘solid frame’, unable to postulate the necessary existence of a third, hypothetical or theoretical space – a psychoanalytic space – Freud reverts back to the only other space wherein the possibility of psychoanalysis retains some legitimacy: his private offices and his own imagination.

8.

In conclusion, let’s look back at Studies on Hysteria. Indeed, the eventual break between Breuer and Freud is already obvious in the final section of this work, written by Freud alone. Here, in “The Psychotherapy of Hysteria”, Freud looks back at early sections of the book, and the case studies described, and states: ‘I must confess that during the years which have since passed – in which I have been unceasingly concerned with the problems touched upon in it – fresh points of view have forced themselves upon my mind. These have led to what is in part at least a different grouping and interpretation of the factual material known to me at the time’. Here, in a prescient description of his future reliance on spatial imagery, Freud argues that this ‘different grouping and interpretation of the factual material’, which leads him to discerning for the first time ‘resistance’ in his patients (the outer shell of the mechanism of repression), is a little bit like coming across an hitherto unknown doorway. ‘The situation may be compared with the unlocking of a locked door,’ he writes, ‘after which opening it by turning the handle offers no further difficulty’.

Hans Blumenberg, in The Readability of the World (2022), offers further context, and an explanation, as to why this may have been the historical moment when Freud first considered ‘resistance’ and the imagery of a door, locked or otherwise. For this was the beginning of a long process by which Freud needed to not only overcome the resistance of his patients, but the resistance of the public in general to his ideas. It may be recalled above, in Freud’s anecdote about reprimanding his incoming patients for not closing the door behind them when entering his office, that Freud noted ‘a sense of disappointment when they entered the empty waiting room’. As with much else in that anecdote, this is perhaps a projection of Freud’s own feelings, his own sense of disappointment at seeing his waiting room empty, his authority unrecognised.

Blumenberg takes us back to a period when this feeling was more palpable. Studies in Hysteria coincides with Freud lecturing in neuropathology at the University of Vienna. The source of ‘embarrassment’ (as Blumenberg calls it) is that Freud was denied access to clinical patients to use in his lectures. This was a time when such lectures had a theatrical edge, demonstrations of behaviours and their treatment being performed to a stunned and rapt audience. ‘Denied access to the clinic’s patients following his appointment to a teaching position,’ Blumenberg states, ‘he was prevented from reproducing even on the smallest scale what had made the greatest impression on his in his whole education: the demonstrations of hysterics by Charcot that he had regularly attended in Paris.’ In 1892-1893, Freud’s course was titled “On Hysteria”. For the next few summer semesters it was called “Theory of Hysteria”, then “Hysteria” in 1896 and 1897 summer semesters. During the winter semesters from 1895-1896, Freud also lectured under the title: “The Major Neuroses”. But without patients to partake in theatrical demonstrations his audience dwindled, the lecture hall emptied. ‘All this,’ Blumenberg states, ‘without the spectacular “cases” needed to create the impression of mastery. Hence, the great leap, methodically as well as “didactically”, of presenting himself in multiple disguises as the complete object of analysis – by means of mere dream literature.’ And so, from 1899 – the year he published The Interpretation of Dreams – Freud lectured to near empty rooms on the topic, “Psychology of Dreams” for two summers, before dramatically shifting to “Introduction to Psychotherapy”, until the winter of 1909 when the course became titled “Psychoanalysis”.

And yet, as Blumenberg states:

Despite the familiar titles, the lecture sequence reveals a striking caesura: a “Psychology of Dreams” allowed the absence of demonstrations to pass unnoticed… Through a surprising turn, Freud had made a virtue of necessity, even if it was resisted by his contemporaries. He had managed to present authentic material by performing a remarkable trick that neither his audience nor his readers could see through at the time: he had made object and subject identical.

And, by collapsing this distinction between object and subject, Freud collapsed, too, the distinction between literal and figurative language, effectively blocking the imagination.

Fifteen years after the first publication of the Introductory Lectures, Freud published New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (1932). The first lecture in this collection is numbered Lecture XXIX, in order to provide the illusion of continuity with the previous Introductory Lectures. In this respect, this new volume is a sort of ‘third term’ in Freud’s course on psychoanalysis. This series of lectures, however, was never formally delivered, due to Freud’s advanced age and physical condition. As he states in the preface: ‘If, therefore, I once more take my place in the lecture room during the remarks that follow, it is only by an artifice of the imagination; it may help me not to forget to bear the reader in mind as I enter more deeply into my subject.’ And so begins the lecture, once more to an empty room, but this time without embarrassment, without disappointment, even when the stage and the stalls no longer have a solid frame.

In Breuer’s words, Freud’s ‘mythology is then complete.’

If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, and you would like to support independent scholarship and criticism, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: consider signing up to this newsletter for free (or updating to a paid subscription)(preferably the latter).

And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more paying subscribers, to ensure that it continues.