The Endurance of Things

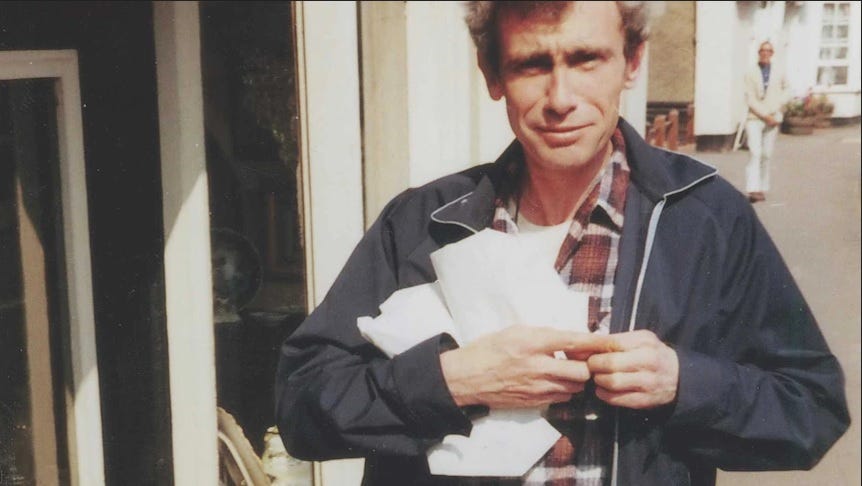

On the literary imagination of Randolph Stow

1.

The novels of Randolph Stow, especially his earlier works, before he left the country for good, sit awkwardly in the annals of Australian literature. It may be worth examining why.

His career began brightly enough, winning the Miles Franklin Award for his third novel, To the Islands, in 1958, when he was only twenty three years old (as he later said about Xavier Herbert, ‘in Australia prizes matter’). Another two novels followed, then a children’s book, by which time Stow had ostensibly left the country for good, finally settling in Suffolk, England, in 1969. But then, in a paper published in 1971, he wrote about ‘the assumptions and delusions, hopes and dreams’ that lie behind that national literature, and he pointed out that what interested him most was the element of ‘self-contradiction’ contained within it.

Although he also said at the time that the ‘mythopoeic’ activity of many of his fellow writers and visual artists – like Patrick White and Sidney Nolan – may be useful in developing a ‘truly Australian’ art, which may help ‘illuminate the life of a fairly new nation not absolutely sure where it is going’, he did not seem to include his own work in the same category. He seemed, instead, to be more interested in exploring this element of ‘self-contradiction’ that lurked beneath.

Indeed, ten years earlier, in another paper, he admitted to being conscious of ‘gaping cracks’ between his own conception of writing fiction and ‘some theoretical Australian literature.’ His own stated preference was for ‘the concept of a literature based on figures in a landscape, more naked and disturbing than a Border ballad or a Spanish romance, in which eternal things are observed with, always, the eyes of the newborn.’

There is, in fact, a particular figure in the landscape of each of Stow’s early Australian novels which may guide us here in reconsidering these works anew. At first this figure – a waterhole, a pool, a ford, a billbong – may seem innocuous enough. After all, it is a commonplace image in any Australian novel, especially ones in regional settings. But it is the placement of the figure of the waterhole, and its repeated use, in all of Stow’s early Australian novels, that makes it stand out in a particular way.

It could very well point to a conception of fiction which challenges the very notion of a national literature.

2.

The waterhole figure is introduced in the crucial scene of Stow’s debut novel, A Haunted Land (1956):

She stood up and walked to the edge of the Pool until she found a place where the trees were thick. Quickly she took off her clothes and slipped into the water. . . And below me, she thought, are the bunyips, wondering what on earth is happening. For the natives believed the Pool to be inhabited by malignant spirits, eager to seize any swimmer who trespassed in their element.

On an isolated Western Australian property, Anne Maguire has taken to horse riding, to escape her claustrophobic family situation. But on this particular day, after swimming at a waterhole, she has a sexual encounter Charlie, an Aboriginal farmhand.

He was wet; he had been swimming. His clothes were in his hands, held modestly about his thighs. In the sun his dark body glistened with the water that had not yet dried.

A variation of this waterhole figure also appears in Stow’s next novel, The Bystander (1957). Keithy is twenty-two years old, but with a mental age of twelve. One day, faced by a flooded ford, he impulsively lifts Diana, his parents’ Latvian housemaid and cook, and starts carrying her across the water.

She could not return the scrutiny of those strange grey eyes. . . . Suddenly, as sometimes happens for no reason, the afternoon became unreal, she was in a dream in which a simpleton was carrying her across a river. . . .

She came back to him out of the dream and found him standing in mid-stream, staring at her as if he were lost; and then, as she looked around, he tried to kiss her. . .

Each of these crucial scenes, occurring within or nearby some waterway, is literally embedded within the landscape. Each scene also marks the moment in which a central character achieves self-awareness. But each scene also includes, or directly leads to, some event which impedes this self-awareness, and results in some tragedy occurring at conclusion of each novel.

In A Haunted Land, after the crucial scene by the pool, Anne begins to have doubts about her sexual encounter with Charlie. Finally she tries telling her brother Patrick what happened, but in doing so, the true nature of the event is changed.

“Don’t you see, Pat, can’t you see what I’m trying to tell you?”

“Yes. Yes, I see. He. . . he forced you.”

She accepted that in silence. She had not intended to spare herself, but she saw his suggestion as an offering.

Anne lies to save herself. And Patrick takes Charlie out into the bush, shoots him in the back, and buries him. Although this event is not mentioned again for the remainder of the book (except briefly toward the end, when it is too late), their silence, and Anne’s deception, ricochets throughout the family. Their father’s ambitions to found a family dynasty are destroyed when his children turn against him, and each other. Finally, Patrick himself is killed.

In The Bystander, the crucial scene at the ford ends with Diana breaking free from Keithy’s arms. She runs away from him, and soon after marries Keithy’s best friend, an older neighbour named Patrick Leighton. Keithy feels doubly betrayed, and the tensions of this strange love triangle – especially after the marriage between Patrick and Diana sours, collapsing into bitterness – leads to the novel’s horrific finale.

All the characters of the novel are brought together in the last pages to fight a bushfire, accidentally started by Keithy. What is interesting about this final scene is that it effectively re-enacts the initial crucial scene of the novel.

And as it had been that day at Malin when he had carried her across the ford, suddenly he had picked her up in his arms, and he was watching her. And for a moment she looked into his mind.

The faraway men beating at the fire could not hear her. She screamed and screamed again, and the sound went up to the sky, muffled, unreal. And he looked at her, half accusingly, and said softly: “I’d go through fire for you.”

3.

Stow never allowed these first two novels to be republished. However, this figure of the waterhole resurfaces in his later novels, following the same pattern, and operating in the same way. But with one critical difference: that which previously impeded the emergence of self-awareness is more deliberately singled out, and a more sustained effort to overcome it, is given a central place in each subsequent novel.

The crucial scene of Stow’s next novel, To the Islands (1958), is once more framed by the figure of a waterhole, a billabong at Onmalmeri.

‘Ever seen a ghost, wunong?’

‘I heard ‘em,’ Justin said uncomfortably.

‘Where?’

‘Onmalmeri. Where all the people was murdered.’

A property owner, out surveying his boundary line, comes across two Aboriginal women in the billabong, gathering gadja (lily roots). He angrily beats their husband, who, in retaliation, spears the property owner and kills him. When a search party later find his body beside the billabong, the troopers are gathered and, unable to single out the culprit amongst the Aboriginal camps, they commence to massacre them all.

‘Nowadays,’ Justin murmured, ‘now, at Onmalmeri, you can hear ghosts crying in the night, chains, babies crying, troopers’ horses, chains jiggling.’ His eyes glowed in the shadows.

The figure of the waterhole is central also to Tourmaline (1963). But unlike the billabong, the ford or Pool in Stow’s earlier novels, Lake Tourmaline is bone dry. This lack of water is, in fact, the central theme of the Tourmaline. It is the main reason the mysterious diviner is drawn to the township. The diviner claims to be able to find water for the town, and replenish Lake Tourmaline, thereby saving the people both physically and spiritually. It is here that the figure of the diviner is linked with the figure of the waterhole. Firstly, according to the local Aboriginal culture:

He make baby, too, spirit of children, in the waterholes and Lake Tourmaline and some places. He make everything for us, Mongga. But mostly water.

This is then translated into the Christian tradition:

“He Mongga!” Charlie cried out, from the altar. And from everywhere murmurs and shouts came. “Mongga! Mongga!” And an old strained voice in tears said: “He is Christ.” These vaguely familiar tones I recognised (Oh God) as mine.

In these novels, the ideas impeding the emergence of self-awareness revolve around certain attitudes of the white Australians toward Aboriginal people, and certain myths regarding the Bush, God and the worship of gold (the historical foundations of Australia’s economic structure, which continues to this day based on the same model of mineral extraction). Together these forge the core of the ‘mythology of the white Australians’, which Stow defined as ‘the assumptions and delusions, hopes and dreams that lie behind the literature’.

Heriot, in To the Islands, is labouring under elements of this mythology. First, he unwittingly recreates the scene at Onmalmeri when, during an argument with an Aboriginal man, Rex, Heriot strikes him down with a rock. Believing he has killed him, Heriot then flees into the bush and quickly falls back upon certain postures of this ‘mythology’, by throwing himself at the mercy of both God and the Bush. Here he tries, and fails, to find redemption, through losing himself in the Great Australian Landscape.

And I’m afraid to – do justice to myself. I can only – give myself to the country, and let it do what it likes with me. That would be God’s justice.

He even tries to hasten this self-discovery by mimicking Aboriginality, albeit poorly. Finally, at a sacred Aboriginal burial site overlooking the sea, he waits in death for the mysterious Aboriginal islands of the dead to appear on the horizon. Only when they fail to do so does he realise his journey of self-discovery has come to nought.

My soul . . . my soul is a strange country.

The narrator of Tourmaline is an old man, known only as the ‘Law of Tourmaline’. But it is now a hollow law, powerless. In many respects, this old man carries the burden of Heriot’s failure. In doing so, he relates the story of Tourmaline, and how in the absence of drinking water, and the loss of a sense of community, the township tries to sate its thirst with the false succour of God and, beneath this, the desire for gold.

“You must join us. If you could feel the power – the esprit de corps. A whole population with one idea –”

“A hundred minds with but a single thought,” said Tom, “adds up to but a single halfwit.”

A certain resistance to these national mythologies, however, also appears in To the Islands and Tourmaline.

The failure of Heriot is offset by the success of his friend, Justin – perhaps the true protagonist of the novel – by his returning to the integrity of his Aboriginality. It is Justin who initially recounts the massacre of Onmalmeri. Like Anne Maguire in A Haunted Land and Keithy in The Bystander – both initiated into self-awareness within the figure of the waterhole – the massacre of Onmalmeri is here linked with Justin’s initiation into adulthood.

‘When was that?’ Dixon asked.

‘Nineteen-nineteen,’ said Justin promptly.

‘When you were just born?’ Gunn probed.

‘No, I was young boy then. Just before they cut me, you know, and start me being a man.’

But instead of entering fully into his Aboriginal culture, after the massacre he is raised within the mission where Heriot works. Here Justin becomes Christian. After Heriot flees the mission, it is Justin who follows him into the bush, to ensure that Heriot doesn’t commit suicide. And for the remainder of the novel, while Heriot undergoes his attempt at self-discovery, Justin rediscovers his own culture. Heriot’s failure is at various points in the narrative countered by Justin’s growing acknowledgement of the powers of the dark upon his blood, and the strength of the dead.

Rex – the man Heriot believes he has killed – is considered recalcitrant and a troublemaker because he does not conform to life at the mission. But upon recovering, he is amongst the party that searches for Heriot and Justin. At last, the reconciliation between Heriot and Rex – white and black Australia – is, significantly, mediated by Justin.

In Tourmaline, the Lake has become barren, the landscape is dry. All seems lost. Even the diviner, who temporarily raises hopes, ultimately fails to find water. Instead, Tourmaline is subjected to further strictures and control; and a cultish organisation which Kestrel, the cruel and greedy publican, returns to exploit.

But there is a glimmer of resistance in the old man’s narrative. He begins writing the story of Tourmaline at the point when Kestrel departs the town, effectively handing it over to the diviner. The story ends when the diviner fails and Kestrel returns. Although tempted by the diviner’s promises, the old man finally realises that the diviner (then Kestrel) intends to replace him as the ‘Law of Tourmaline’. But in his writing he achieves a critical remove which enables him to employ his imagination, and through this, albeit briefly, to discern his own individuality.

To begin, I must imagine and invent.

And through a sort of ritual chant, across this introductory chapter – arguably the finest opening chapter in Australian literature – he reinvents his town, and recreates its populous, calling to his aid the powers of the imagination.

Imagine her there. . .

Imagine him there. . .

And imagine . . .

Easy, easy to imagine them there forever. . .

Imagine him there. . .

Imagine her there. . .

Imagine him there. . .

Finally, he evokes himself: Imagine me well.

The novel ends with his final immersion into these waters, the figure of the waterhole reappearing, not in the literal landscape, but within himself. The literal waterhole achieves metaphoricity. The memory of this is first awoken by the dusty air:

I walked out, into the thick wind.

It was like swimming under water, in a flooding river. Dust sifted into my lungs I was drowning.

And then the memory itself is imagined:

I have seen rain in Tourmaline. Can you believe that? How can you? You have not seen that green, that green like burning, that covers all the stones on the red earth . . . . And pools, lakes, oceans of blowing flowers.

4.

So how does this waterhole figure operate in Stow’s novels? Another novelist, Robert Musil, provides a clue in A Man Without Qualities: ‘If one wants to pass through open doors easily, one must bear in mind that they have a solid frame: this principle,’ the narrator argues, ‘is simply a requirement of the sense of reality. But if there is such a thing as a sense of reality – and no one will doubt that it has its raison d’être – then there must also be something that one can call a sense of possibility.’

What Musil is talking about is a necessary relationship between reality and the imagination. ‘It is reality that awakens possibilities,’ he concludes, ‘and nothing could be more wrong than to deny this.’ Stow’s waterhole figure operates in the same way as Musil’s doorway figure. For Stow, the landscape provides the stable sense of reality in which the possibilities of entering and returning anew from the water are awakened.

For Stow, the Australian landscape is characterised primarily by a particular sort of emptiness; due, in part, to the country being so vast, and so ancient.

‘The sense of the past is linked with its vastness,’ Stow wrote once in an article. ‘It is a country in which one can be aware of a tremendous range of time. . . . And on the hottest days, in the most desolate places, it is possible to know, almost kinetically, the endurance of things.’

This particular sense of emptiness discourages the attribution of meaning to the land; it refutes the Great Australian Landscape. The ‘mythology of the white Australians’ – built upon a society, narrow and young in comparison to the land it occupies – cannot encompass it; although it can impede our awareness of it. Overcoming these impediments, this stable value then provides the background against which the individual can emerge, the fulcrum with which to lever oneself out of the dominant national mythologies.

‘When one is alone with it, one feels in one way very small, in another gigantic,’ says Stow of the Australian outback: ‘In the cities, personality is fenced in by the personalities of others. But alone in the bush, with maybe a single crow (and that sound on a still day widens the world by half) a phrase like “liberation of the spirit” may begin to sound meaningful.’

Regarding his own fiction, Stow cites the importance of the resonance and association in his own writing: ‘Just look at the literal meaning of resonance, the etymological meaning, it means to sound again, to ring again. And what I aim to do, why I concentrate so much on the real world in my novels, is that I want to ring bells in people’s minds, to make them relate to their own experience, to say it is like that, yes, I remember, it is like that. Another meaning of resonance in my mind is associations,’ Stow states: ‘it makes one think.’

It is this simultaneous operation of resonance and association – particularly in his figure of the waterhole, a place of possibility, embedded within the otherwise empty reality of the landscape – which provides Stow’s novels with a unique sense of perspective. It create1s a critical remove, which comes to see – and enables his reader’s to see also – certain ideas about the conventional fiction of the ‘Nation’ more and more as an impediment to the free creation of literary fiction, and to the emergence of our own sense of critical individuality.

In other words, it makes one think.

5.

If the narrator of Tourmaline sees a moral to his own tale, it is this: There is no sin but cruelty. Only one. And that original sin, that began when a man first cried to another, in his matted hair: take charge of my life, I am close to breaking.

This sin is the abdication of a particular conception of individuality.2 Overcoming this temptation is at the heart of all Stow’s fiction, a heart exposed in his next novel, The Merry-Go-Round in the Sea (1965). Rob Coram is six years old when his older cousin, Rick Maplestead, whom he idolises, leaves to fight in the Second World War. Rob is raised on certain national mythologies – from his family, their history, and their shared literature. These ideas come to form an integral part of his vision of the country.

He built in his mind a vision of Australia, brave and sad, which was both what soldiers went away to die for and the mood in which they died. Deep inside him he yearned towards Australia: but he did not expect ever to go there.

Only Harry and the soldiers could go to Australia.

In a sense, too, Rick shares in this vision, until he faces the reality of war. Upon his return to Australia, Rick can no longer fit back into an unquestioning acceptance of the Australian way of life. It is a feeling of unease only compounded by being held up as Rob’s idol. For if only soldiers could go to Australia, then Rick is, for Rob, at least, the epitome of ‘Australian’.

Thus follows a slow disintegration of ideals, culminating in the final pages of the novel, in a sorrowful confrontation between the two characters.

‘Look, kid,’ Rick said, ‘I’ve outgrown you. I don’t want a family, I don’t want a country. Families and countries are biological accidents. I’ve grown up, and I’m on my own.’

Shaken into self-consciousness, Rob finally reaches a realisation, which itself could stand as a final statement, not just for this novel, but for the outcome of the struggle which all Stow’s previous novels enacts – and which their readers may re-enact.

The world the boy had believed in did not, after all, exist. The world and the clan and Australia had been a myth of his mind, and he had been, all the time, an individual.

What is interesting here, in confirmation of all that has been so far said, is that this final confrontation is precipitated in the novel through the operation of a familiar figure in the landscape. It is a figure which underwrites a conception of literature which makes us imagine ourselves anew.

The final scene commences when Rob and Rick go swimming in a waterhole.

‘They used to tell me there was a bunyip in it, to.’

‘What is a bunyip, Rick?

‘God knows. Probably some sort of fertility spirit, like a rainbow serpent in the Kimberleys.’

‘It wouldn’t hurt you, then?’

‘I dunno,’ Rick said. ‘It might make you pregnant.’

‘Aww.’ . . . .

‘It was a sacred place,’ Rick said, ‘that’s certain. And I suppose the local yamidgees had the usual ideas about the spirits of unborn children being in the water. That ring of stones, you know, that our boundary fence runs through, that could have been something to do with fertility. Hey, it’s probably making new men of us, swimming here.’

‘I am a new man,’ said the boy unhappily.

‘So am I,’ said Rick.

6.

Randolph Stow once admitted to being ‘puzzled’ by the recurring motif associated to the word ‘garnet’ which he found in Patrick White’s, A Fringe of Leaves (1976). Stow considered the possible derivation of this image from the word ‘pomegranate’, which is the fruit which Persephone tasted, keeping her partially in the underworld for evermore. This led Stow to write the poem, “A Pomegranate in Winter”, dedicated to White.

In many respects, Stow’s own reputation in Australia has some affinity with the fate of Persephone. This fate was sealed early on, and is summed up in the title of Vincent Buckley’s influential but critically limited 1961 essay, “In the Shadow of Patrick White”. But I’d suggest a close examination of the recurring motif of the ‘waterhole’ in Stow’s own work offers a more fruitful appreciation of his place in our literature. And a more interesting confrontation between White and Stow also appears in Stow’s final ‘Australian’ novel, Midnite: the story of a wild colonial boy (1967). Often dismissed as a mere children’s book, this novel is perhaps the culmination of all Stow’s previous novels, and his most subversive. Following from The Merry-Go-Round in the Sea, it is as if we enter into the imaginary world of an Australian child, such as young Rob from that previous novel. In terms of literary satire, this Midnite prefigures Stow’s only worthy heir in Australian writing, David Foster.

Leaving the Hidden Valley, Midnite and his gang of animals (reminiscent of Keithy’s menagerie in The Bystander), are pursued by, and are in turn, in pursuit of, the ‘mythology of the white Australians’. At the centre of this work, Midnite happens across an explorer-poet, based on White’s Voss (1957).

This explorer was a rather miserable German man called Johann Ludwig Ulrich von Leichardt zu Voss, but in Australia he called himself Mr Smith.

Significantly, regarding the motif of the waterhole in Stow’s work, Mr Smith suddenly dies from lack of water immediately after claiming proprietorship over the Australian landscape.

“It’s the end of the Outback,” said the explorer, “where come poets and explorers to die.”

This is an often cited scene from the book. But what is usually overlooked is what comes directly after ‘Voss’ dies. And this could stand as a final statement, not just for this novel, but for the outcome of the struggle which all Stow’s previous novels enact, each in their in way, and that is the possibilities of the imagination, and the struggle for individuality against the national closure of the imagination. Here Midnite and his gang come across a pass in the rocky desert mountains, beyond the barren salt-lake:

They tramped down this passage, hearing every sound that they made echo back and forth between the cliffs, and came out into a place like a paddock among the boulders, in which was a long deep pool, with waterlilies and ducks floating on it, and grass and trees all around it, and a great many comfortable caves.

“Oh, bravo, Major!” cried Midnite, throwing Trooper O’Grady’s hat in the air. “It is another Hidden Valley, and even better.”

Then he and Gyp dived into the pool and had a swim.

In the early 1970s – and like Rick in The Merry-Go-Round in the Sea – Randolph Stow may have moved away from Australia (he died in 2010); but like Rob in the same book, Stow’s novels remain a part of our literary landscape. And each of them stands as a particular and unique figure in that imaginary landscape, which works to ensure our conception of the whole always remains unsettled.

This is, of course, also the process of mimesis, as defined by Luiz Costa Lima, as the production of difference within an horizon of similitude, as we’ve considered previously here.

The same insight is at the heart of Albert Camus’ work, as we’ve seen previously, with regards to his conception that the necessity of thinking and acting without the prop or support of abstract systems, doctrines, or ideologies, on the grounds that each operates through the false promise of alleviating from the individual the responsibility for their life, and their responsibility to others. As we’ve noted previously here.